In addition to the iconic scene in Jim Henson’s Labyrinth, or appearances in animated TV shows and video games, M.C. Escher’s work has adorned the covers of albums like Mott the Hoople’s 1969 debut and the speculative fiction of Italo Calvino and Jorge Luis Borges. A big hit with hippies and 1960s college students, writes Heavy Music Artwork, his mind-bending prints became associated with “questioning accepted views of normal experience and testing the limits of perception with hallucinogenic drugs.” While he appreciated his cult following, Escher “did not encourage their mystical interpretations of his images.” Replying to one enthusiastic fan of his print Reptiles, who claimed to see in it an image of reincarnation, Escher replied, “Madame, if that’s the way you see it, so be it.”

Rather than illustrate higher states of consciousness or metaphysical entities, Bruno Ernst writes in The Magic Mirror of M.C. Escher, the artist intended to create practical, “pictorial representation of intellectual understanding.” Illustrations, that is, of philosophical and scientific thought experiments. The son of a civil engineer, Escher began his studies in architecture before moving to drawing and printmaking.

The challenge of creating built environments—even seemingly impossible ones—always seemed to occupy his mind. Along with themes from the natural world, a high percentage of his works center on buildings—inspired by formative early years in Rome and his admiration for Islamic art and Spanish architecture.

In the 50s and 60s Escher’s art piqued the interest of academics and mathematicians, an audience he found more congenial to his vision. He corresponded with scientists and incorporated their ideas into his work, meanwhile claiming to be “absolutely innocent of training or knowledge in the exact sciences.” In the 50s, Escher “dazzled” the likes of mathematicians like Roger Penrose and HSM Coxeter. In turn, notes Maev Kennedy, he “was inspired by Penroses’s perspectival triangle and Coxeter’s work on crystal symmetry.”

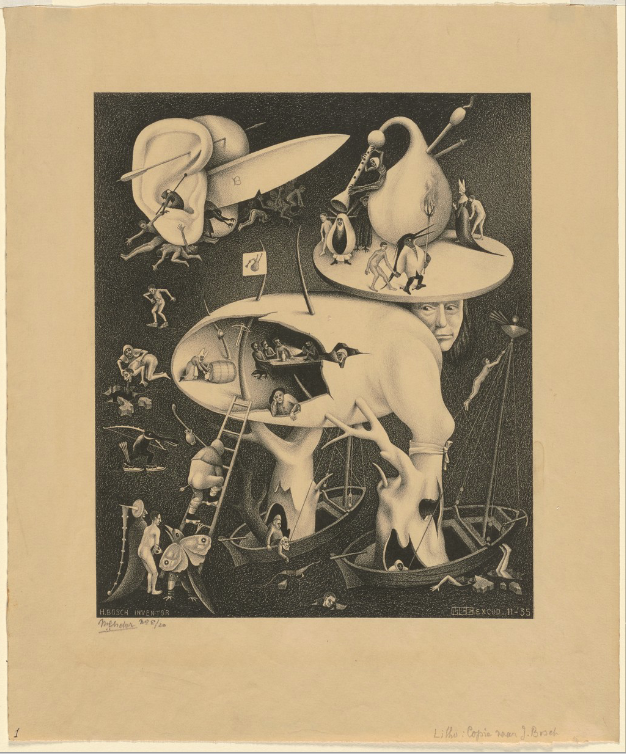

For all the excitement he created among mathematicians, it took a bit longer for Escher to get noticed in the art world. When Penrose’s uncle showed Escher’s version of the perspectival triangle to Picasso, “Picasso had heard of the British mathematician but not of the Dutch artist.” Escher’s fame spread outside of the sciences in part through the interests of the counterculture. He may have shrugged off mystical and psychedelic readings of his prints, but he had an innate penchant for the marvelously weird (see his copy of a scene, for example, from Hieronymus Bosch, above, or his surreal print Gravity, below).

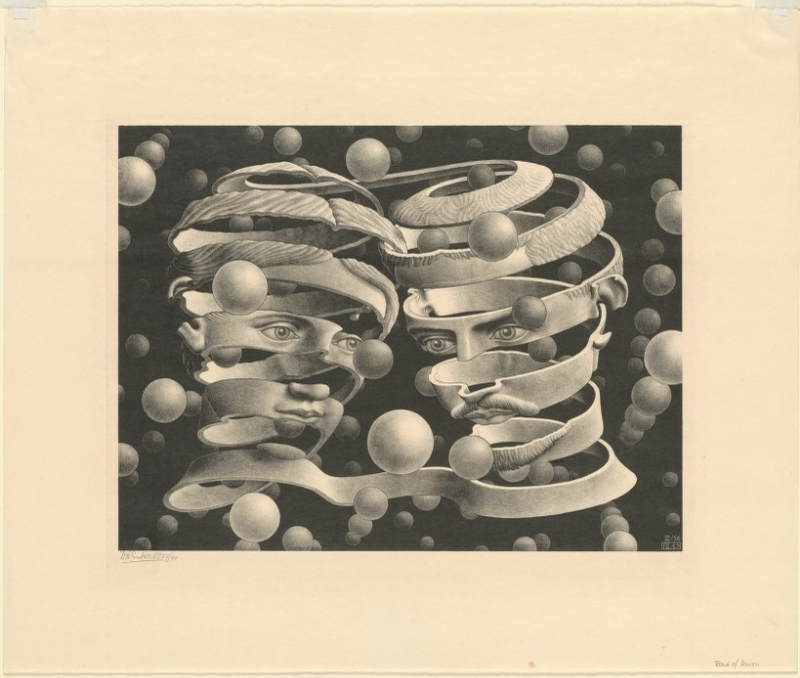

See the prints pictured here and a few dozen more digitized in high resolution at Digital Commonwealth, courtesy of Boston Public Library, who scanned their Escher collection and made it available to the public. Zoom into the fine details of prints like Inside Saint Peter’s, further up—a finely rendered but otherwise not-especially-Escher-like work—and the labyrinthine Ascending and Descending at the top. Whether—as Harvard Library curator John Overholt confesses—you’re a “nerd who loves M.C. Escher” for his mathematical mind, an artist with a mystical bent who loves him for his hallucinatory qualities, or some measure of both, you’ll find exactly the Escher you’re looking for in this digital gallery.

Related Content:

M.C. Escher Cover Art for Great Books by Italo Calvino, George Orwell & Jorge Luis Borges

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply