Even the most avid James Joyce fans surely have times when they open Finnegans Wake and wonder how on Earth Joyce wrote the thing. Painstakingly, it turns out, and not just because of the infamous difficulty of the text itself: he “wrote lying on his stomach in bed, with a large blue pencil, clad in a white coat, and composed most of Finnegans Wake with crayon pieces on cardboard,” writes Brainpickings’ Maria Popova. By the time Joyce finished his final novel, the eye problems that had plagued him for most of his life had rendered him nearly blind. “The large crayons thus helped him see what he was writing, and the white coat helped reflect more light onto the page at night.”

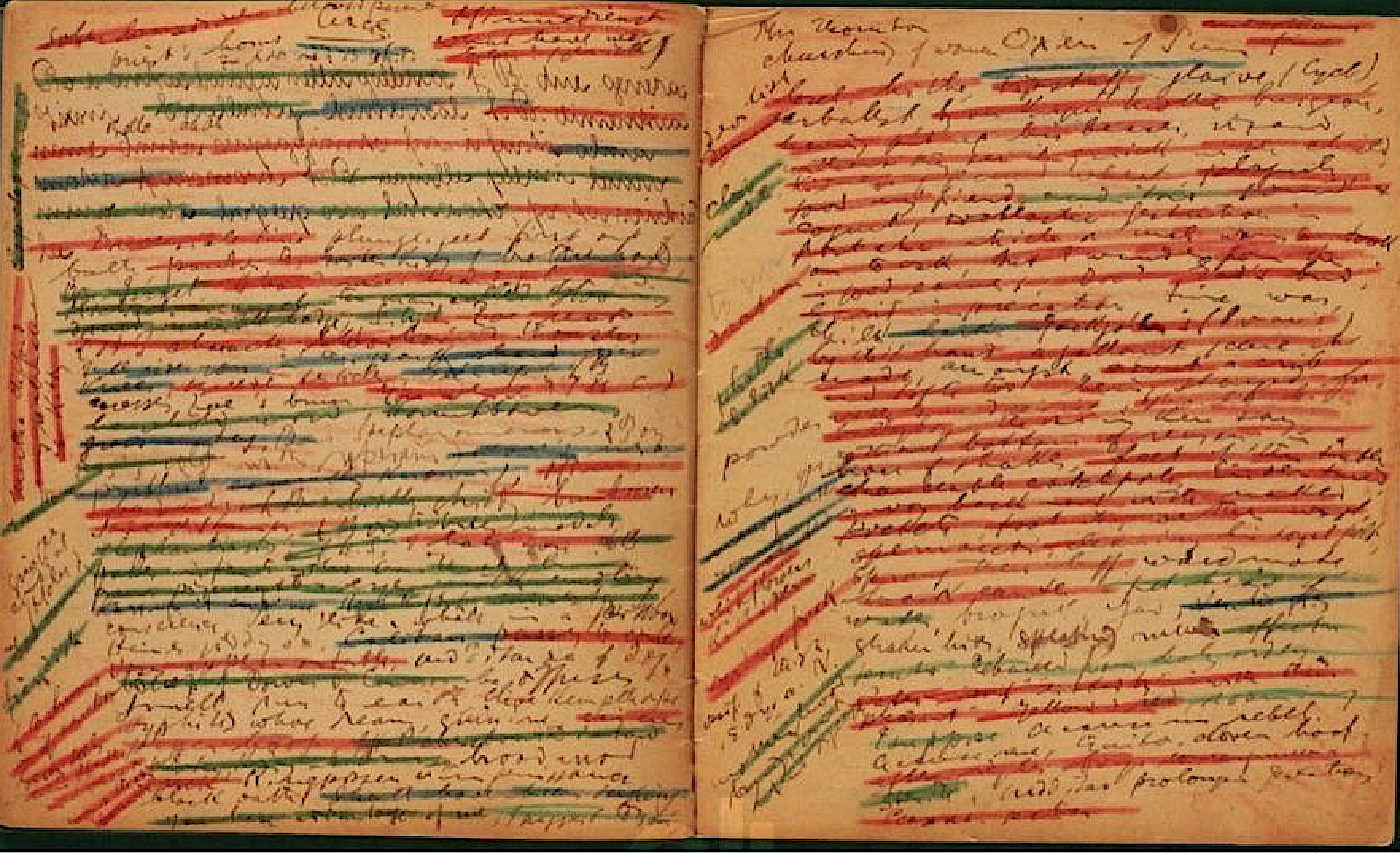

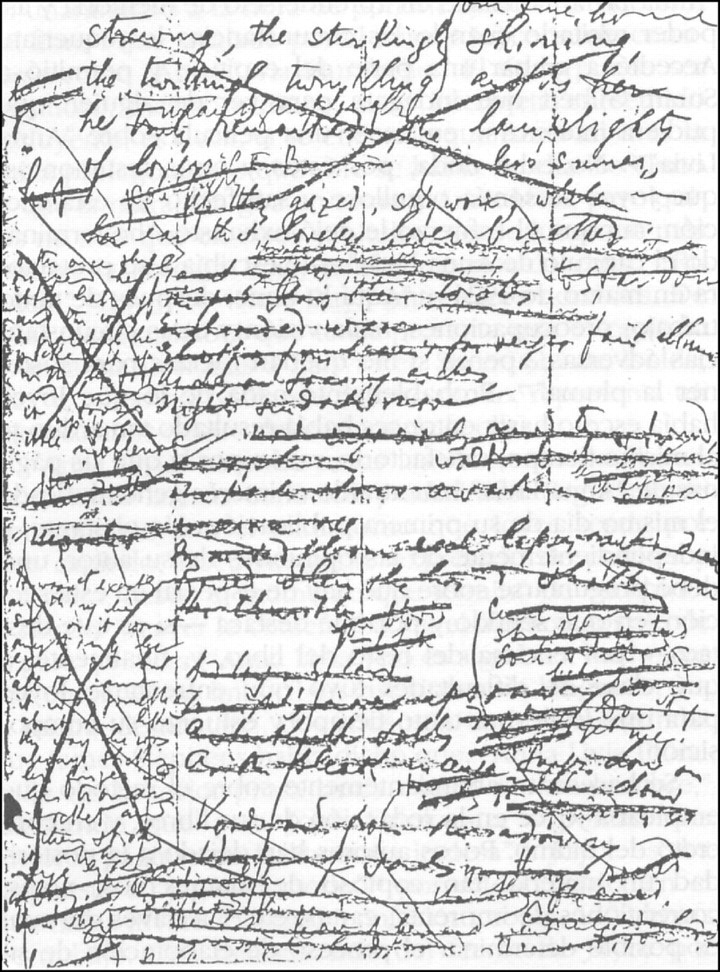

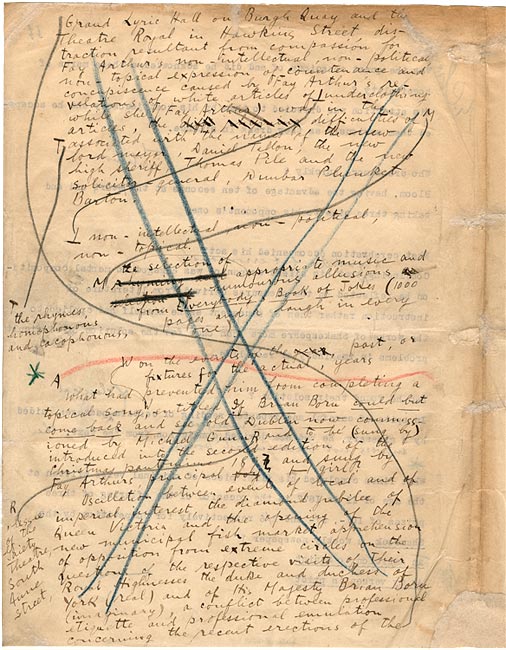

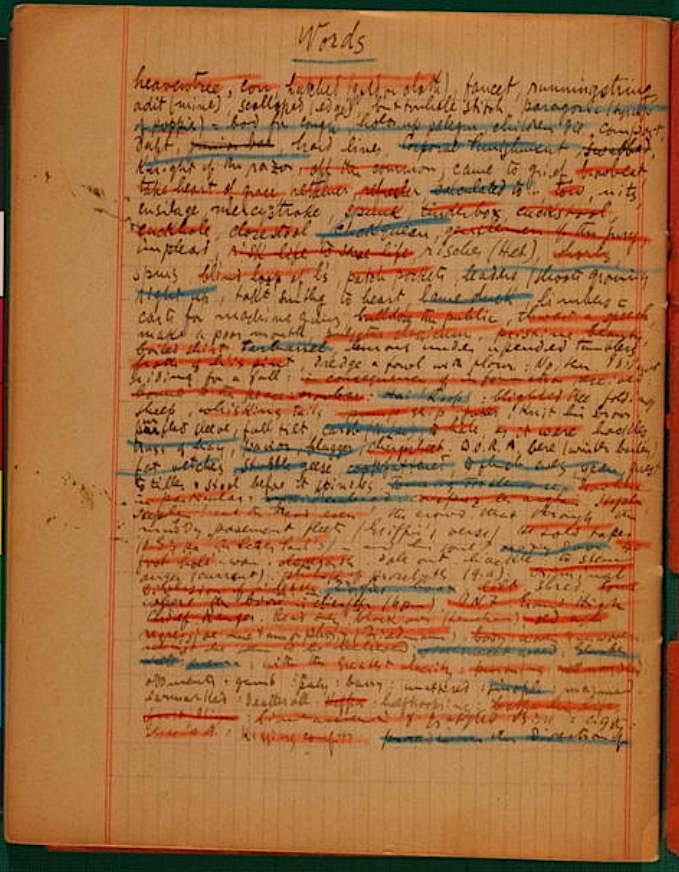

Crayons also had a place in his intricate revision process. “Joyce used a different colored crayon each time he went through a notebook incorporating notes into his draft,” writes Derek Attridge in a review of The Finnegans Wake Notebooks at Buffalo, a compilation of all the extant working materials for Joyce’s final novel. He also calls Joyce’s colored crayon method part of “a scrupulousness which has never been satisfactorily explained” — but then, much about Joyce hasn’t, and may never be. “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant,” he once wrote, “and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.”

But he wrote that about Ulysses, a breeze of a read compared to Finnegans Wake, but a work that has surely inspired even more scholars to devote their careers to its author. Some become full-blown “Joyceaholics,” as Gabrielle Carey recently put it in the Sydney Review of Books, and must eventually find a way to “break up” with the object of their unhealthy literary fixation. She got hooked when a piano teacher introduced her to Molly Bloom’s soliloquy at the end of Ulysses. “The last page of Ulysses confirmed my youthful idea that there was such a thing as star-crossed lovers,” Carey writes. “Molly and Leopold were clearly meant for each other.” The conviction with which that idea resonated, she writes, “was to lead me down so many ill-fated paths.”

Carey stepped onto the long path that would lead her away from Joyce when she looked upon his manuscripts: “It was only then, almost thirty years after reading Joyce for the first time, that I noticed a tiny revision to the final paragraph.” Joyce’s insertion added a critical, deflating phrase to the passage that had brought her Joyce in the first place: “and I thought well as well him as another.” Whatever your own experience with Ulysses, Finnegans Wake, or any of Joyce’s other enduring works of literature, the actual pages on which he crafted them (the color ones seen here from Ulyssses and the black and white from Finnegans wake) can offer all kinds of illumination. They also remind us that the books must have required nearly as much mental fortitude to write as they do to properly read.

Related Content:

James Joyce: An Animated Introduction to His Life and Literary Works

Why Should You Read James Joyce’s Ulysses?: A New TED-ED Animation Makes the Case

James Joyce Reads From Ulysses and Finnegans Wake In His Only Two Recordings (1924/1929)

James Joyce, With His Eyesight Failing, Draws a Sketch of Leopold Bloom (1926)

See What Happens When You Run Finnegans Wake Through a Spell Checker

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Is the incorrect spelling of “ensuring” attributable to Joyce or the author of this article? If the former, it should be accompanied by a “[sic]”. If the latter, well, you need to learn the difference between “ensure” and “insure” … they are not interchangeable.