Concrete or visual poetry does not get much respect these days. Tersely defined at the Poetry Foundation as “verse that emphasizes nonlinguistic elements in its meaning” arranged to create “a visual image of the topic,” the form looks like a clever but frivolous novelty in our very serious times. It has seemed so in times past as well.

When Guillaume Apollinaire published his 1918 Calligrammes, his major collection of poems after he fought on the front lines of the first world war, he included several visual poems. Critics like Louis Aragon, “at his most hard-nosed,” notes Stephen Romer at The Guardian, “criticized it sharply for its aestheticism and frivolity.”

Apollinaire also wrote of war as a dazzling spectacle, a tendency that “raised the hackles of critics.” One can see there is moral merit to the objection, even if it misreads Apollinaire. But why should visual poetry not credibly illustrate phenomena we find sublime, just as well as it illustrates potted Christmas trees?

Indeed, the form has always done so, argues prolific visual poet Karl Kempton, until it took a “dystopian” turn after World War I. In his vast history of visual poetry, Kempton reaches back into ancient Buddhist, Sufi, European, and Indigenous cultural history. Forms of visual poetry, he writes, “are associated with ongoing traditions and numerous unfolding pathways traceable to humankind’s earliest surviving communication marks.”

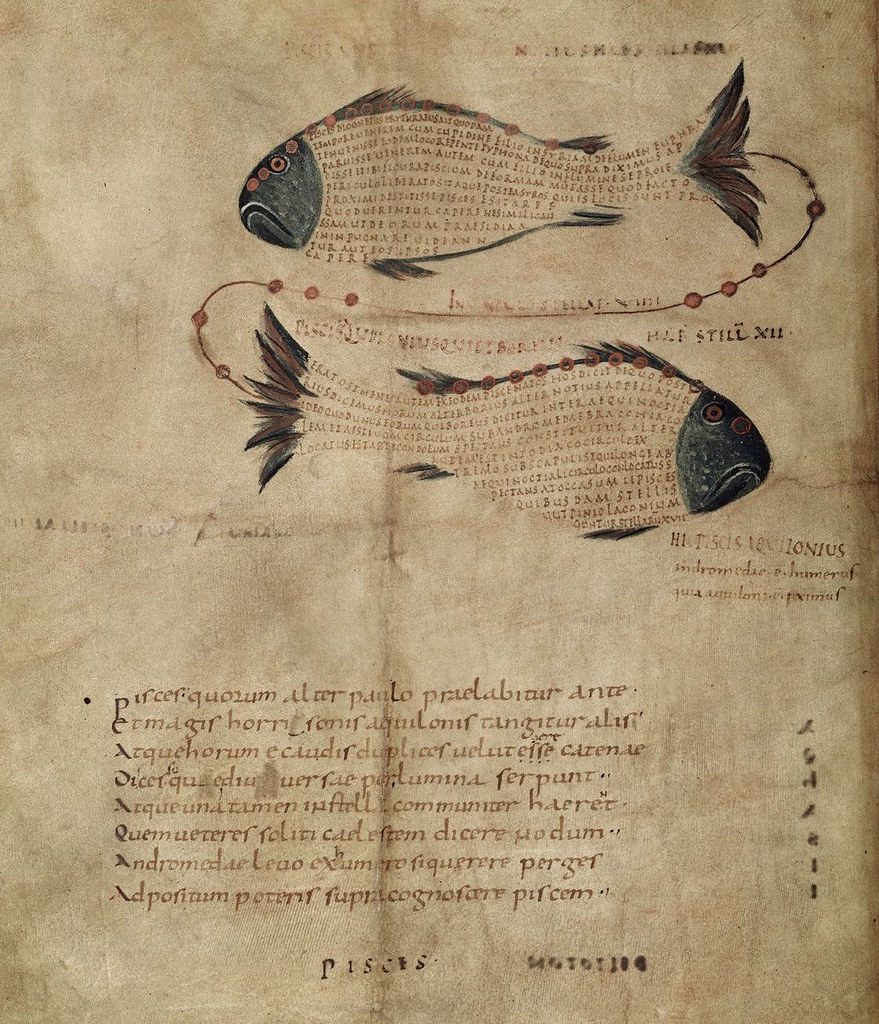

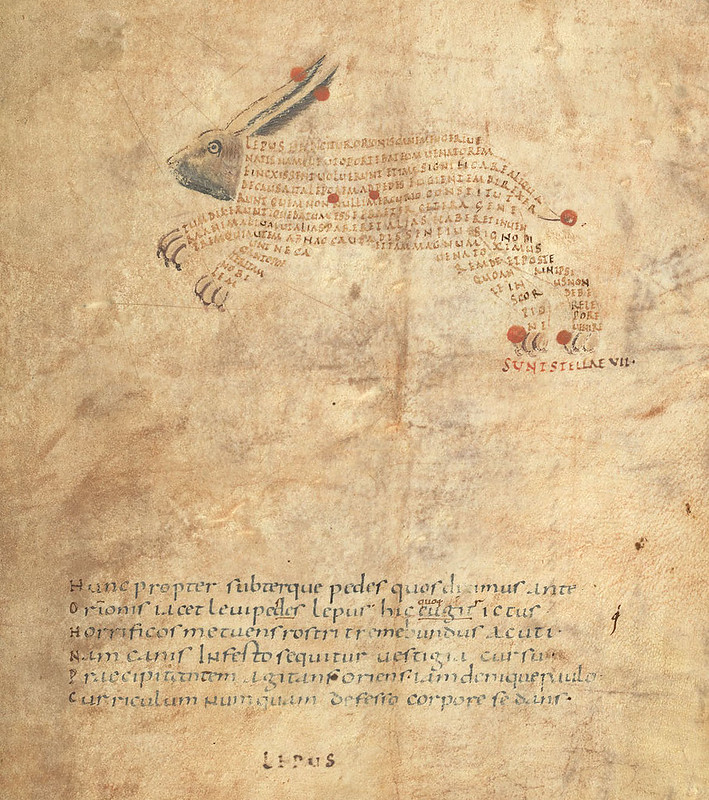

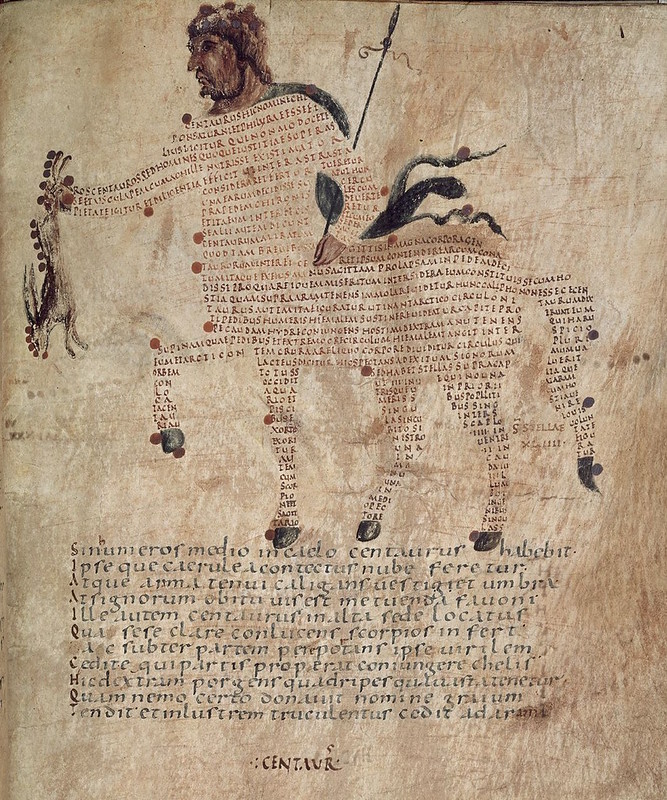

Not as ancient as the examples into which Kempton first dives, the pages here from a manuscript called the Aratea nonetheless show us a use of the form that dates back over 1000 years, and incorporates “nearly 2000 years of cultural history,” writes the Public Domain Review. “Making use of two Roman texts on astronomy written in the 1st century BC, the manuscript was created in Northern France in about 1820.”

The text that has been arranged into images wasn’t originally poetry, though one might argue that arranging it thus makes us read it that way. Instead, the words are taken from Hyginus’ Astronomica, a “star atlas and book of stories” of somewhat uncertain origin. The poems in lined verse below each image are by 3rd century BC Greek poet Aratus (hence the title), “translated into Latin by young Cicero.”

If this feels like hefty material for a literary production that might seem more whimsical than awe-inspiring, we must consider that the manuscript’s first—and necessarily few—readers would have seen it differently. The text is a visual mnemonic device, the red dots showing the positions of the stars in the constellations: an aesthetic pedagogy that threads together visual perception, memory, imagination, and cognition.

“The passages used to form the images describe the constellation which they create on the page,” the Public Domain Review writes, “and in this way they become tied to one another: neither the words nor the images would make full sense without the other to complete the scene.” We are encouraged to read the stars through art and literature and to read poetry with an illustrated mythological star chart in hand.

The Aratea is a fascinating manuscript not only for its visually poetic illuminations, but also for its significance across several spans of time. Its physical existence is necessarily tied to the British Library where it resides. One of the institution’s first artifacts, it was “sold to the nation in 1752 under the same Act of Parliament which created the British Museum.”

“Part of a larger miscellany of scientific works,” including several notes and commentaries on natural philosophy, as the British Library describes it, the medieval text uses classical sources to contemplate the heavens in a form that is not only pre-Christian and pre-Roman, but perhaps, as Kempton argues, dates to the origins of writing itself.

Related Content:

700 Years of Persian Manuscripts Now Digitized and Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply