The apotheosis of prestige realist plague film, Steven Soderburgh’s 2011 Contagion, has become one of the most popular features on major streaming platforms, at a time when people have also turned increasingly to books of all kinds about plagues, from fantasy, horror, and science fiction to accounts that show the experience as it was in all its ugliness—or at least as those who experienced it remembered the events. Such a work is Daniel Defoe’s semi-fictional history “A Journal of the Plague Year,” a book he wrote “in tandem with an advice manual called ‘Due Preparations for the Plague,’ in 1722,” notes Jill Lepore at The New Yorker.

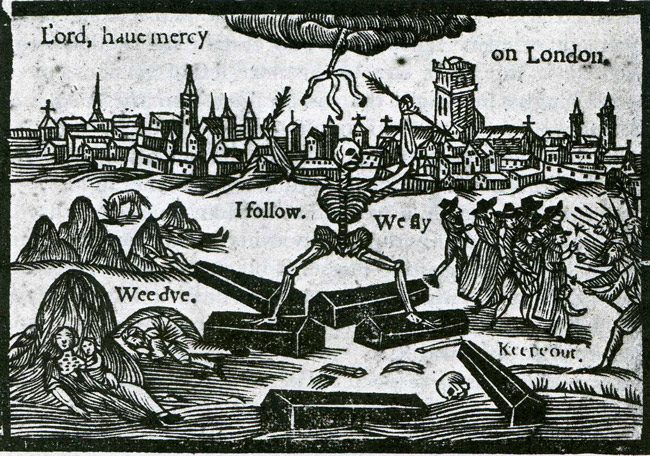

In 1722, Defoe had reason to believe the plague might come back to London, and wreak the devastation it caused in 1665, the “plague year” he detailed, when one in every five Londoners died. This was not a story of heroes making sacrifices to save the city. “Everyone behaved badly, though the rich behaved the worst,” Lepore writes. “Having failed to heed warnings to provision, they sent their poor servants out for supplies,” spreading the infection throughout the city. Defoe earnestly hoped to head off such catastrophe. He wrote to issue an admonition, as he put it, “both to us and to posterity, though we should be spared from that portion of this bitter cup.”

The cup, Lepore writes, “has come out of its cupboard.” But so too has the resilience found in Albert Camus’ 1946 novel Le Peste (The Plague), based on a real cholera outbreak in Algeria in 1849. Though fictional, it draws on Camus’ study of historical plagues and his experience as a member of the French Resistance. Camus seems to have found the plague as metaphor particularly uplifting, nicknaming his twins Catherine and Jean, “Plague” and “Cholera,” respectively.

Whether we see it as a story of a siege brought on by sickness, or an allegory of an occupation, Camus wrote of the novel that “the inhabitants, finally freed, would never forget the difficult period that made them face the absurdness of their existence and the precariousness of the human condition. What’s true of all the evils in the world is true of plagues as well. It helps men to rise above themselves.” Defoe might disagree, but plagues in his time were not also accompanied by widespread Nazism, a double crisis that might doubly force us to “reflect on what is real, what is important, and become more human,” says Catherine Camus of the soaring new popularity of her father’s novel.

We can do this through reading in our real-life quarantine. “Reading is an infection,” Lepore writes, “a burrowing into the brain: books contaminate, metaphorically, and even microbiologically” as physical objects capable of ferrying germs. Plagues are mass-existential crises on the level of WWII or the Lisbon earthquake that shook the faith of Europe’s intellectuals. They are also settings for love and terror, from Boccaccio and Gabriel Garcia Marquez to Edgar Allan Poe and Margaret Atwood.

Vulture has published an “essential list” of 20 plague books to read, including many of the classics mentioned above, and a book that is hardly remembered but might be thought of as an ancestor to Atwood’s plague-ridden futures: Mary Shelley’s The Last Man, published in 1826 during the second of two virulent cholera pandemics. In the novel, Shelley claims to have discovered the story in prophetic writing about the end of the 21st century, telling of a disease that wipes out the human race. If you’d rather not indulge that kind of fantasy just yet, you’ll find varying degrees of imaginative and soberly realist fiction and history in the list of plague classics below, all freely available at Project Gutenberg.

A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe

History of the Plague in London by Daniel Defoe

Loimologia: or, an Historical Account of the Plague in London in 1665 by Hodges et al.

The Last Man by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

The Masque of the Red Death by Edgar Allan Poe

The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio

A History of Epidemics in Britain by Charles Creighton

A History of Epidemics in Britain, Volume II

An account of the plague which raged at Moscow, in 1771 by Charles de Mertens

Cherry & Violet: A Tale of the Great Plague by Anne Manning

Libraries may have shut their possibly contaminated books behind closed doors, bookstores may be deemed nonessential, but reading—and writing—about plague years feels like a necessary cultural activity to help us understand who we are apt to become in such times.

Related Content:

The History of the Plague: Every Major Epidemic in an Animated Map

Isaac Newton Conceived of His Most Groundbreaking Ideas During the Great Plague of 1665

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Awesome content. Very Informative.

A best content ever