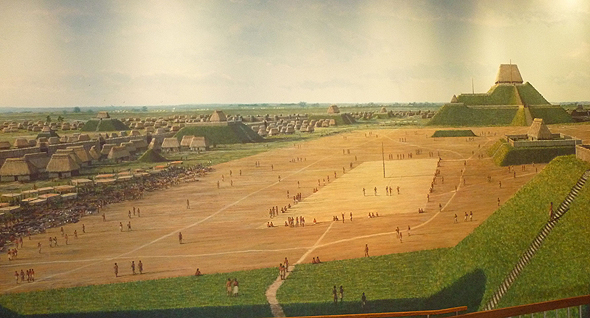

In our current epoch of human history, when populations of major cities swell into the tens of millions, an urban center of 30,000 people doesn’t seem very impressive. 1,000 years ago, a city that size was larger than London or Paris, and sat atop what is now East St. Louis. At its height in 1050, Annalee Newitz writes at Ars Technica, “it was the largest pre-Colombian city in what became the United States…. Its colorful wooden homes and monuments rose along the eastern side of the Mississippi, eventually spreading across the river to St. Louis.”

It is called Cahokia, but that name comes from later inhabitants who themselves didn’t know who built the ancient metropolis, Roger Kaza explains, “We really have no idea what the builders called their city.” Also, no one, including the people who settled there not long afterward, knows what happened to the city’s inhabitants. Archaeologists call these lost indigenous societies the Mississippians.

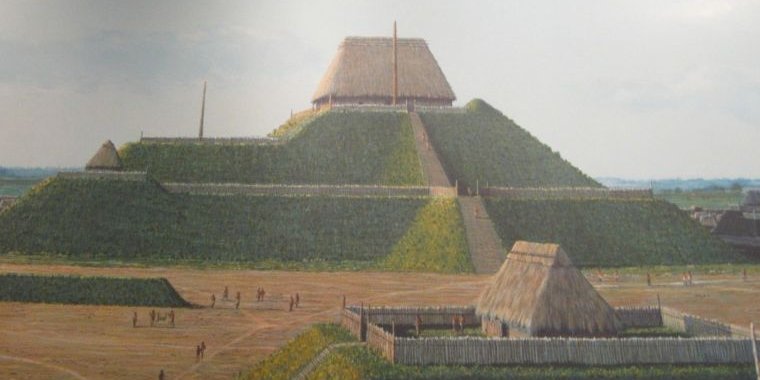

They occupied a territory along the river of nearly 1,600 hectares during what is called the Mississippian period, roughly between 800 and 1400 A.D. The society built mounds, “some 120,” notes UNESCO, who have designated Cahokia a world heritage site. (See an introductory video below from the Cahokia Mounds Museum Society and two artist recreations elsewhere on this page.) The largest of these mounds, Monk’s Mound, stands 30 meters high.

Cahokia is “a striking example of a complex chiefdom society, with many satellite mound centres and numerous outlying hamlet and villages.” Size estimates vary. UNESCO’s is more conservative “This agricultural society may have had a population of 10–20,000 at its peak between 1050 and 1150,” they write—still, at any rate, a major city at the time. The Mississippian civilization left behind “pottery, ceremonial art, games and weapons,” Kaza notes. “Their trade network was vast, stretching from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.”

The mounds were a symbol of both earthly and religious power, and the city appears to have been a pilgrimage site of some kind, with remains of what may have been a 5,000 square foot temple at the top of Monk’s Mound and evidence of human sacrifice on other mounds. “A circle of posts west of Monk’s Mound has been dubbed ‘Woodhenge,’ because the posts clearly mark solstices and equinoxes,” writes Kaza.

But the true strength of Cahokia, as in all great metropolises, was economic power. As archaeologist Timothy Pauketat of the University of Illinois notes, “it just so happens that some of the richest agricultural soils in the midcontinent are right up against that area of Cahokia.” Corn grew plentifully, produced surpluses, and the society grew rich. Then, seemingly inexplicably, it collapsed. “By the time European colonizers set foot on American soil in the 15th century, these cities were already empty,”

One recent study suggests two natural climate change events several hundred years apart explain both Cahokia’s rise and fall: “an unusually warm period called the Medieval Climatic Anomaly” gave rise to the region’s abundance, and an abrupt cooling period called “the Little Ice Age” brought on its end. Climatologists have found evidence showing how a drought in 1350 caused the pre-Columbian Mississippian corn industry to implode.

Pauketat finds this explanation persuasive, but insufficient. Politics and culture played a role. It’s possible, says archeologist Jeremy Wilson, who coauthored the recent climate paper, that “the climate change we have documented may have exacerbated what was an already deteriorating sociopolitical situation.”

Evidence suggests mounting conflict and violence as food grew scarcer. Climatologist Broxton Bird argues that the Mississippians left their cities and “migrated to places farther south and east like present-day Georgia,” Angus Chen writes at NPR, “where conditions were less extreme. Before the end of the 14th century, the archaeological record suggests Cahokia and other city-states were completely abandoned.”

We should be careful of seeing in this contemporary language any close parallels to the situation major cities face in the 21st century. Just one link in the global supply chain that drives climate change today can employ 10,000–20,000 people. But perhaps it’s possible to see, in the distant indigenous past of North America, the not-so-future vision of a migratory future for the inhabitants of many cities around the world.

via Art Technica and Messy Nessy

Related Content:

Native Lands: An Interactive Map Reveals the Indigenous Lands on Which Modern Nations Were Built

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Your headline reads: “A Medieval Metropolis Existed In What’s Now St. Louis, Then Mysteriously Disappeared in the 14th Century”

This should be corrected. The “medieval metropolis” existed in what is now Collinsville, Illinois. St. Louis is in Missouri–on the *west* side of the Mississippi; Cahokia Mounds (not be be confused with Cahokia, IL, which is a proper modern city in the same general area) is in ILLINOIS, on the *east* side of the river.

It’s really not that complicated. Please amend at your earliest convenience.

Regards,

Suse Sternkopf

Hi Suse,

I regret to inform you that you are wrong. If the world were just, you’d be stricken with polio such that your fingers could never again tarnish another page with such a foolish comment.

All the best,

Tom Petty

They won’t, because they just republish things.

Also, the article is clickbait from the title. The author uses “medieval” so loosely it means nothing.

“Medieval” Europe this is not, that’s for sure.

I lived in Mt. Carmel, IL in 1967–1968 (about 150 miles to the East of St. Louis) and visited the “Cahokia Indian Mounds” on occasion with my parents. I am very bothered by something that has been removed from the record entirely. I recall visiting a museum there, where they (presumably archaeologists) had unearthed the remains of apparent chieftans from the burial mounds. These fairly well preserved remains were housed in glass cases and were fully 7′ plus tall with flaming red hair. there was no explanation given as to who these people were, much like the knowledge today. We do not know who these people were.

The fact that this has been entirely removed from the historical record is very surprising. I have even corresponded with a current archaeologist working at the dig site there, and she completely dismissed my account as fantasy.

I am not suggesting a conspiracy here, but what is it about extremely tall, particularly red haired humans from our past that is hidden?!

I find this article fascinating. I think back to how shocking it may have seemed to me a few years ago with a different perspective. The existance of other cultures does not negate my Biblical beliefs.

A Girl Scout camp existed on top of a Indian Buriel Mound!

I went to Camp there in Grafton, Illinois in the 1940’s. I’m assuming the Girl Scouts did not know this history.

After a hard rain on day we discovered what we thought was a rock, was indeed a skull!

But, it would be extremely interesting to ascertain why they were wiped out. What kind of disease?

It means the 1400s you must have an open mind

Did you put the skull back leave alone respect it…you woulnt like your remains tampered with would you

A Naturalist took the skull to a museum I presume. I was around 8–10 years old. The Girl Scouts did respect our find.

It’s hard to recall since that was around 1948- 1950. The rock was by the door of our cabin.

I used to work on the farms adjacent to Momks. And used to sled on it In the early 60’s

Hey Tom–

Don’t take my word for it–look at a map.

As for your boorish and abusive comment “If the world were just, you’d be stricken with polio such that your fingers could never again tarnish another page with such a foolish comment.”

Poor little boy…little, little boy.