In the contest for the title of the most American historical figure of them all, Thomas Morton’s name can’t be left out. Businesslike, litigious, given to rhapsodies over nature, and not resistant to turning celebrity, he was also — in a characteristically American manner — born elsewhere. Back in Devon, England, he’d made his name as a lawyer, representing members of the lower class in court, but in 1622 he was hired by investor Sir Ferdinando Gorges on a trip to handle his affairs in the North American colonies. This was just two years after the founding of Plymouth Colony, whose success had inspired many an English businessman to contemplate getting in on the New World action himself. In 1624, Gorges sent Morton across the Atlantic again, this time with everything needed to found a colony of his own.

Morton was not a Puritan, nor was he “on board with the strict, insular, and pious society they had hoped to build for themselves,” as Atlas Obscura’s Matthew Taub puts it. Though his own colony of Merrymount became Plymouth’s rival in the fur trade, for the Puritans “the problem wasn’t only that Morton was taking goods and commerce away from Plymouth, but that he was giving that business to the Native Americans, including trading guns to the Algonquins. With Plymouth’s monopoly dissolved and its perceived enemies armed, Morton had perhaps done more than anyone else to undermine the Puritan project in Massachusetts.” And that was before Morton erected Merrymount’s 80-foot, antler-topped maypole, around which he invited residents to “drink, dance, and frolic.”

Obviously, Morton’s reign as a “lord of misrule” (as Plymouth’s governor William Bradford deemed him) could not be borne for long. “During the 1628 festivities, a Puritan militia led by Myles Standish invaded Merrymount and chopped down the maypole,” writes Taub, noting that the incident inspired Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1832 short story “The May-Pole of Merry Mount.” Morton also turned out to be an able chronicler of the period himself, at least after the subsequent tribulations that saw him sentenced to death by starvation, helped to survive by the Native American tribes with whom he had maintained good relations, safely returned to England, and frustrated in his attempts to return to the colonies. Around 1630, he did what any true American, official or aspiring, would do: put together a lawsuit.

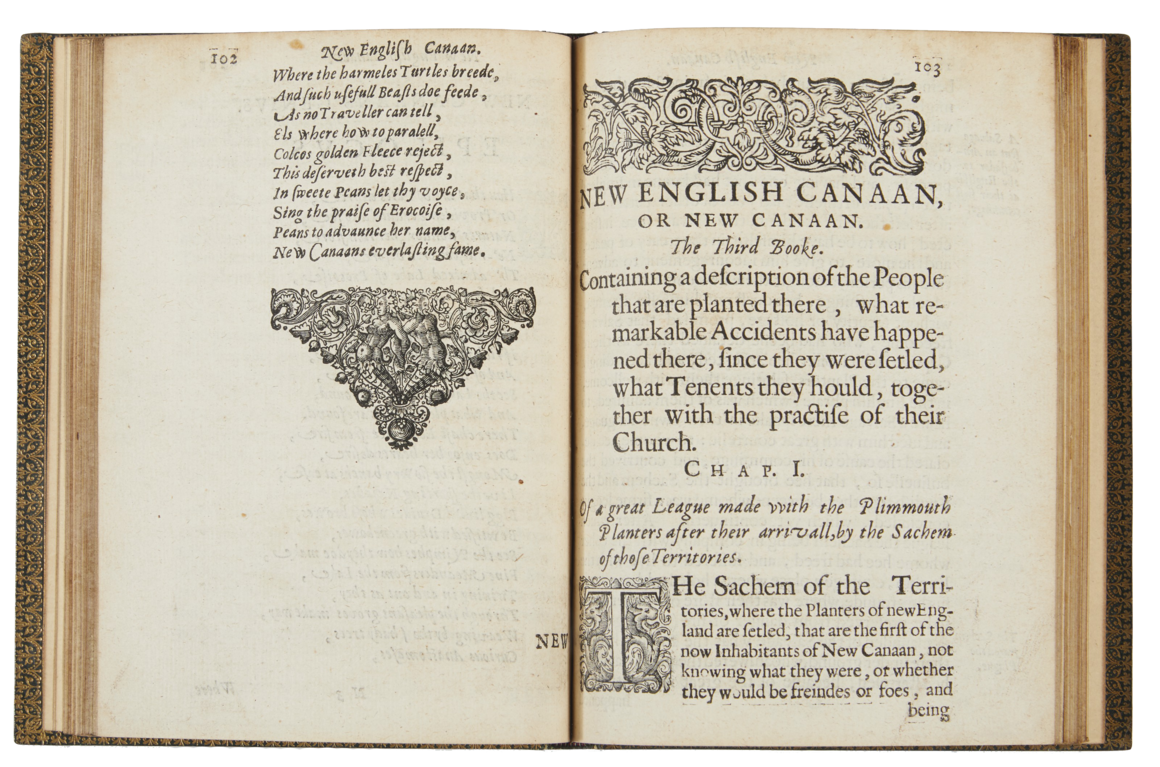

Morton demanded, writes World History Encyclopedia’s Joshua Mark, “that the government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony demonstrate by what authority they exercised their power,” arguing for the revocation of its charter “because the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony had not only misrepresented themselves in obtaining the charter but had no right to colonize the region in the first place as it was legally in Gorges’ patent.” As the long (and in any case futile) legal proceedings dragged on, Morton got the idea of turning his extensive briefs for the trial into “a three-volume work of history, natural history, satire, and poetry” called New English Canaan, a Biblical allusion underscoring Morton’s critical view of the Puritans as “abusing the natives and the land for profit and then justifying their actions in the name of their god and the scriptures.”

Linda Cantoni at Hot off the Press writes that “the first two books of New English Canaan are mostly non-controversial, containing Morton’s observations on the native Americans, whom he respected greatly, and on the rich natural resources in New England. It was in the third book that Morton rolled up his sleeves and got down to his real purpose of skewering the New England Puritans, who, he said, ‘make a great shewe of Religion, but no humanity.’ ” As a result, writes Mental Floss’ Jake Rossen, “his book was perceived as an all-out attack on Puritan morality, and they didn’t take kindly to it. So they banned it,” making New English Canaan what Christie’s called “America’s first banned book” when they auctioned a copy off for $60,000. But you can read it for free at Project Gutenberg, bearing in mind the most American lesson of all from the life of Thomas Morton: when all else fails, publish a tell-all memoir.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

The British Library Digitizes Its Collection of Obscene Books (1658–1940)

Read 14 Great Banned & Censored Novels Free Online: For Banned Books Week 2014

When Christmas Was Legally Banned for 22 Years by the Puritans in Colonial Massachusetts

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply