After about a century of indirect company rule, India became a full-fledged British colony in 1858. The consequences of this political development remain a matter of heated debate today, but one thing is certain: it made India into a natural destination for enterprising Britons. Take the aspiring clergyman turned Nottingham bank employee Samuel Bourne, who made his name as an amateur photographer with his pictures of the Lake District in the late eighteen-fifties. When those works met with a good reception at the London International Exhibition of 1862, Bourne realized that he’d found his true métier; soon thereafter, he quit the bank and set sail for Calcutta to practice it.

It was in the city of Shimla that Bourne established a proper photo studio, first with his fellow photographer William Howard, then with another named Charles Shepherd. (Bourne & Shepherd, as it was eventually named, remained in business until 2016.) Bourne traveled extensively in India, taking the pictures you can see collected in the video above, but it was his “three successive photographic expeditions to the Himalayas” that secured his place in the history of photography.

In the last of these, “Bourne enlisted a team of eighty porters who drove a live food supply of sheep and goats and carried boxes of chemicals, glass plates, and a portable darkroom tent,” says the Metropolitan Museum of Art. When he crossed the Manirung Pass “at an elevation of 18,600 feet, Bourne succeeded in taking three views before the sky clouded over, setting a record for photography at high altitudes.”

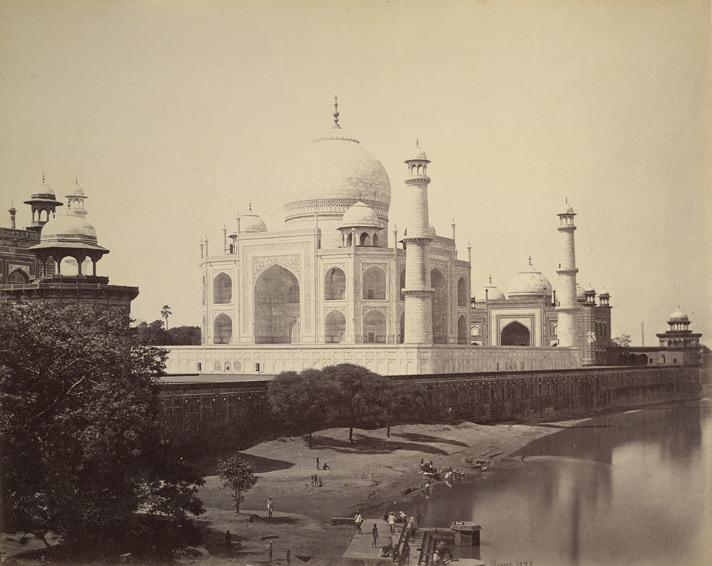

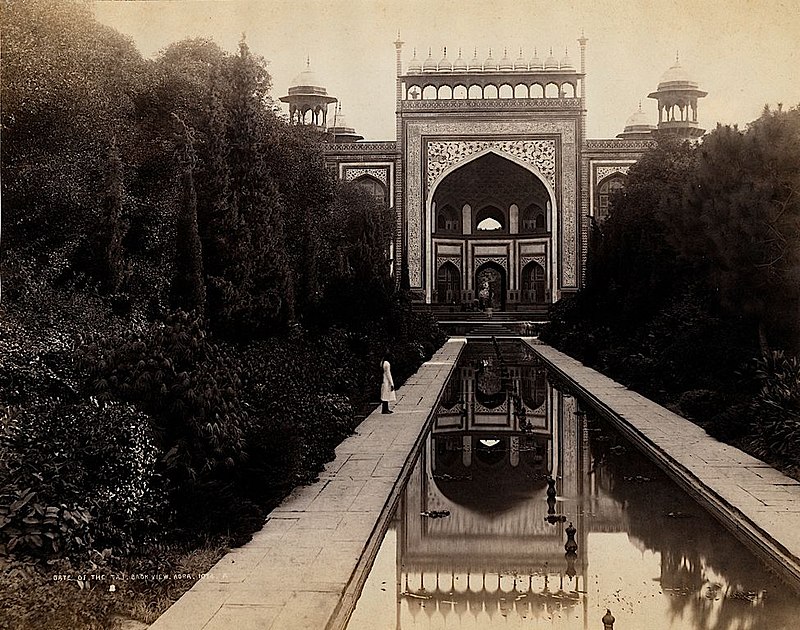

Though he spent only six years in India, Bourne managed to take 2,200 high-quality pictures in that time, some of the oldest — and indeed, some of the finest — photographs of India and its nearby region known today.

In addition to views of the Himalayas, he captured no few architectural wonders: the Taj Mahal and the Ramnathi temple, of course, but also Raj-era creations like what was then known as the Government House in Calcutta (see below).

Colonial rule has been over for nearly eighty years now, and in that time India has grown richer in every sense, not least visually. It hardly takes an eye as keen as Bourne’s to recognize in it one of the world’s great civilizations, but a Bourne of the twenty-first century probably needs something more than a camera phone to do it justice.

Related content:

The First Photograph Ever Taken (1826)

The Oldest Known Photographs of Rome (1841–1871)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Great 👍/ 👌

==========

India 🇮🇳/ BHARAT Civilization is 5000 or more years old.

Great photos!

Thankyou mam .i am from Kasganj near Agra (India/Bharat)

Thankyou mam .i am Gulshan from Kasganj near Agra (India/Bharat)