Those who find their way into the rich emotional and aesthetic realm of Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky (see our collection of Free Tarkovsky movies online) might at first assume that nobody can put the experiential appeal of his cinema into words. The well-known writer and Tarkovsky fan Geoff Dyer demonstrated this, in a sense, with his highly entertaining book Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room, which ostensibly describes the director’s acclaimed Stalker but actually heads off in a thousand different digressive directions, all of them driven by the writer’s appreciation for the movie. Pictures like Stalker, Solaris, Nostalghia, or The Mirror may set off within you a range of reactions to film you’d never thought possible, but wouldn’t that only make them more difficult to talk about? Rarely do the much-discussed musical rather than intellectual properties of cinema as an art form seem as relevant as when you watch Tarkovsky; the old line comparing writing about music to dancing about architecture comes to mind.

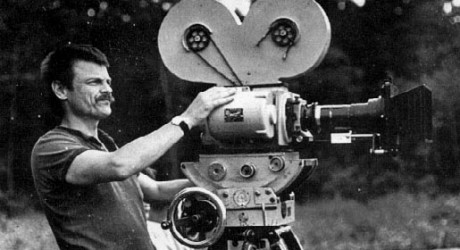

But Tarkovsky himself thought of film as sculpture, as he explains in the posthumously published treatise on his craft Sculpting in Time. The book has much to teach about the unique artistic potential of the medium as this master understood it, and it reveals that, indeed, one can speak cogently about Tarkovsky, and nobody can do it more cogently than Tarkovsky himself. This ability he also displays in the documentary Voyage in Time, from which we’ve previously featured a clip of his advice to young filmmakers. Here we have a less-seen portrait, but one that makes a similarly thorough examination, with interviews, dramatizations, and historical footage, of the auteur’s reality: Donatella Baglivo’s 1983 Tarkovsky: A Poet in Cinema. (Watch it online here.) From Baglivo’s short but choice prompts, Tarkovsky expounds on not just his life and work but the essential importance of fighting, the conceptual nonexistence of happiness, what childhood determines about us, wartime’s impact on fantasies, and the salutary effects of a year laboring in Siberia — all in the first fifteen minutes of this 140-minute argument that film, at its most powerful, doesn’t just get you talking about film; it demands that you talk about existence itself.

Related Content:

Tarkovsky Films Now Free Online

Tarkovsky’s Advice to Young Filmmakers: Sacrifice Yourself for Cinema

Tarkovsky’s Solaris Revisited

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Very First Films: Three Student Films, 1956–1960

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Tarkovsky? The best ever, the master.

Thanks for this.