Click here for larger image, then click again to zoom in.

Backstories of famously accomplished people seem incomplete without some past difficulty or failure to be overcome. In narrative terms, these incidents provide biographies with their dramatic tension. We see Abraham Lincoln rise to the highest office in the land despite the humblest of origins; Albert Einstein rewrites theoretical physics against all academic odds, given his supposed early childhood handicaps. In many cases, these stories are apocryphal, or exaggerated for effect. But whatever their accuracy, they always seem to reflect undeniable character traits of the person in question.

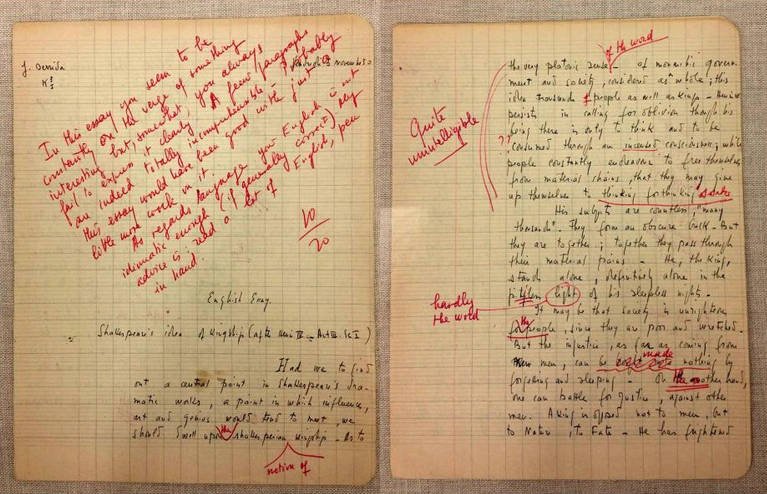

In the case of influential philosopher Jacques Derrida, progenitor of the both beloved and reviled critical theory known as “Deconstruction,” the stories of academic struggle and great mental suffering are well-documented. Furthermore, their details accord perfectly well with the mature thinker who, remarks the site Critical Theory, “can’t answer a simple god-damned question.” The good-natured snark on display in this description more or less sums up the feedback Derrida received during some formative years of schooling while he prepared for his entrance exams to France’s university system in 1951 at the age of 20.

Derrida may have “left as big a mark on humanities departments as any single thinker of the past forty years,” writes The New York Review of Books, but during this period of his life, he failed his exams twice before finally gaining admittance. Once, he “choked and turned in a blank sheet of paper. The same month, he was awarded a dismal 5 out of 20 on his qualifying exam for a license in philosophy.” One essay he submitted on Shakespeare, written in English (above), received a 10 out of 20. The feedback from Derrida’s instructor will sound very familiar to perplexed readers of his work. “Quite unintelligible,” writes the evaluator in one marginal comment. The main comment at the top of the paper reads in part:

In this essay you seem to be constantly on the verge of something interesting but, somewhat, you always fail to explain it clearly. A few paragraphs are indeed totally incomprehensible.

Another examiner—points out the NYRB—left a comment on his work “that has since become a commonplace”:

An exercise in virtuosity, with undeniable intelligence, but with no particular relation to the history of philosophy… Can come back when he is prepared to accept the rules and not invent where he needs to be better informed.

As it turns out, Derrida was not particularly interested in the rules, but in inventing a new method. Even if his “apostasy” caused him great mental anguish—“nausea, insomnia, exhaustion, and despair” (all normal features of any higher educational experience)—it’s probably fair to say he could not do otherwise. Although his intellectual biography, like the history of any revered figure, is unlikely to offer a blueprint for success, there is perhaps at least one lesson we may draw: Whatever the difficulties, you’re probably better off just being yourself.

Related Content:

130+ Free Online Philosophy Courses

8‑Bit Philosophy: Plato, Sartre, Derrida & Other Thinkers Explained With Vintage Video Games

Jacques Derrida Deconstructs American Attitudes

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Erm, that illustration… How come the writing’s in English? Why is it not attributed?

It’s in English because it’s an English class…

By the way, 10/20 isn’t too bad a grade in classe prépa (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classe_pr%C3%A9paratoire_aux_grandes_%C3%A9coles).

Ummm.… It is an English essay–as is stated in the article. Derrida’s name is in the upper left corner and the assignment “English essay” is clearly stated in the written text.

You can only get those notebooks in France. Helps the French to write with regular x heights and perfect leading.

Doesn’t guarantee perfect logic, though. ‘Seyes quadrillage’ is what you’re looking for. It already sounds like anything written on it deserves a doctorate.

http://cycle3.lorca.free.fr/old/tbi/seyesjpg.JPG

Certainly nobody would be better off trying to be Derrida.

The man makes no sense at all. Total Fraud.

You’re wrong.

Derrida has been recognized by numerous reading universities in the world as doctor honoris causa. Total fraud? What have you, “Sem,” pray tell, written or even read in history of philosophy? Do you understand, say, Kant? Does that makes sense to you? Or Husserl? Or Spinoza? Etc. You get my drift.

Derrida has been recognized by numerous leading universities in the world as doctor honoris causa. He has been published and translated in university presses around the world probably more than any other 20 century philosopher. “Total fraud?” Not even partial fraud? Just plain total? What have you, “Sem,” above, pray tell, written or even read in history of philosophy? Do you understand, say, Kant? Does that makes sense to you? Or Husserl? Or Spinoza? Etc. You get my drift. You have to be acquainted with the philosophical tradition Derrida wrote about in order to be able to comprehend him. Like in any other intellectual discipline. But for that you have to understand the word discipline.

Several years too late a reply, but I’m surprised a philosophical eminence would resort to an argument um ad verecundiam. They usually weed that out of you in the first year.