There are too many things people don’t know about Zora Neale Hurston, renowned primarily for her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. That’s not to slight the novel or its significant influence on later writers like Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou, but to say that Hurston’s scholarly work deserves equal attention. A student of famed anthropologist Franz Boas while at Barnard College, Hurston became “the first African American to chronicle folklore and voodoo,” notes the Association for Feminist Anthropology. Before turning to fiction, she traveled the Caribbean and the American South, collecting stories, histories, and songs and publishing them in the collections Mules and Men and Tell My Horse.

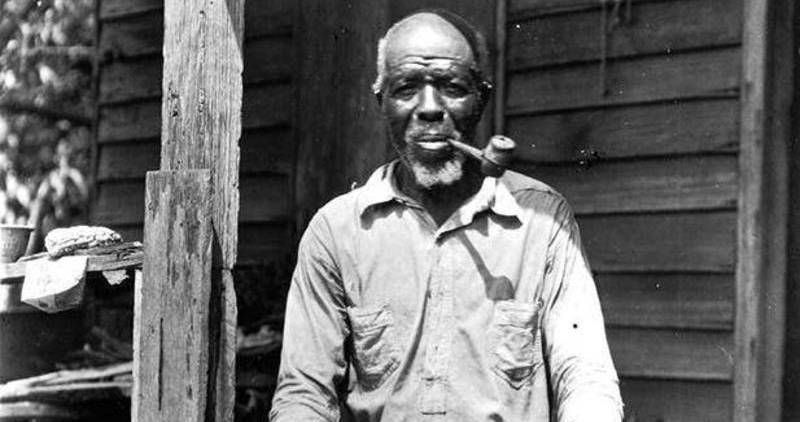

Hurston’s work in ethnography informed her fiction and opened up the field to other African American scholars. It also produced one of the most important works of American nonfiction in the 20th century, a book that, until now, sat in manuscript form at Howard University’s library, where only academics could access it. Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” tells the story of Cudjo Lewis (1840–1935), the last known survivor of the Atlantic slave trade, in his own words. Hurston met Lewis—born Oluale Kossola in what is today the country of Benin—in 1927. She conducted three months of interviews and published a study, “Cudjo’s Own Story of the Last African Slaver,” that same year.

But when she tried to publish the interviews as a book in 1931, she was told she had to change Lewis’ language. “For at least two publishing houses,” writes Meagan Flynn, “Lewis’s heavily accented dialect was seen as too difficult to read.” Hurston refused. Now, the book has finally been published by HarperCollins, with Lewis’s speech intact as Hurston recorded it. HarperCollins editor Deborah Plant tells NPR, “We’re talking about a language that he had to fashion for himself in order to negotiate this new terrain he found himself in.”

As published excerpts of the book show, his speech is not hard to understand. He describes the kind of bewilderment all enslaved Africans must have felt after arriving on alien shores and forced to toil day in and day out under threat of whipping or worse: “We doan know why we be bring ’way from our country to work lak dis,” he says, “Everybody lookee at us strange. We want to talk wid de udder colored folkses but dey doan know whut we say.”

Lewis tells the story of his capture by the King of Dahomey, whose warriors raided his village of Takkoi and sold the captives to American Captain William Foster, operating an illegal operation (the slave trade had been outlawed for almost 60 years). Forced aboard the ship Clotilda with over 100 other African men and women, Lewis was transported to Mobile, Alabama and sold to a businessman named Timothy Meaher. “Cudjo and his fellow captives were forced to work on Meaher’s mill and shipyard,” Gabe Paoletti writes at All That’s Interesting. “As a slave, he started to go by the name ‘Cudjo,’ a day-named given to boys born on a Monday, as Meaher could not pronounce the name ‘Kossola.’”

Deborah Plant sees the rejection of Hurston’s book in the 30s as akin to Lewis’s loss of his name, country, and culture. “Embedded in his language is everything of his history,” she says. “To deny him his language is to deny his history, to deny his experience, which is ultimately to deny him period, to deny what happened to him.”

87 years after the book’s writing, Lewis’s story offers a timely reminder of the history of slavery. The book arrives just after the discovery of what historians and archaeologists believe to be the wreck of the Clotilda, a vessel owned and operated, says AL.com reporter Ben Raines in the video above, by two already wealthy men who smuggled slaves to prove that they could get away with it, then burned the evidence, the ship, to escape detection.

When police arrived at Meaher’s property to charge him with illegally smuggling enslaved people, he “had hidden away the captives,” writes Paoletti, “and had erased all trace of them having been there.” Thanks to Hurston, we have an invaluable firsthand account of what it was like for one West African man who not only endured war and capture at the hands of a rival tribe, but also sale at a slave market, the middle passage across the Atlantic, and forced labor in the deep South—and who lived through the Civil War, Emancipation, Reconstruction and well into the early 20th Century.

Related Content:

Hear Zora Neale Hurston Sing Traditional American Folk Song “Mule on the Mount” (1939)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply