When the Moog synthesizer appeared in the late 60s, musicians didn’t know what it was for, so they found some very creative uses for it, including making novelty tracks like “Pop Corn,” a huge hit for Gershom Kingsley from the 1969 album Music to Moog By. But the Moog was more than a quirky new toy. It was a revelation for what synthesized sound could do, of a technology that seemed like it might have unlimited possibility if harnessed by the right hands. The Moog showed up in 1967 on albums by the Doors, the Monkees, the Byrds—psychedelic bands who understood its futuristic promise.

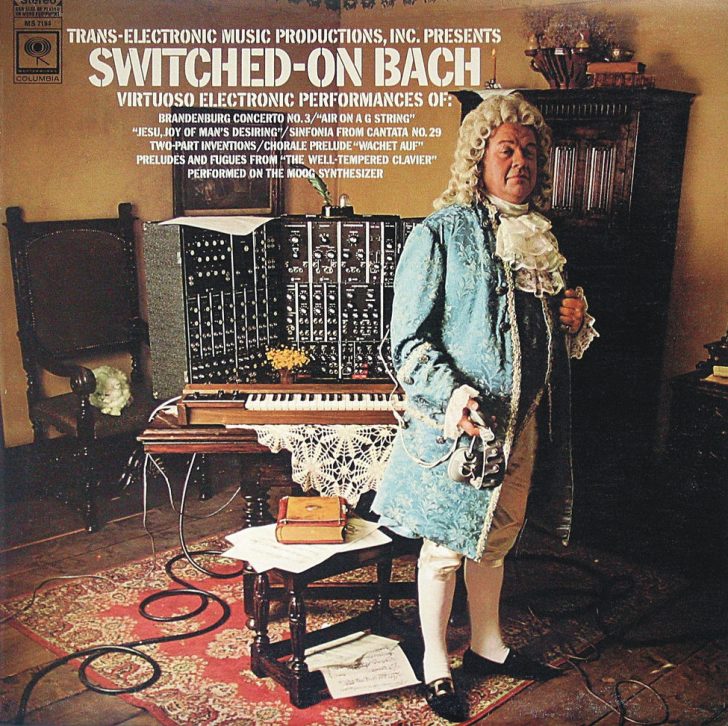

Yet it also entered the homes of millions of listeners through a classical album. In 1968, the Moog featured solo on the highest-selling classical album of all time, Switched on Bach, by electronic composer and pianist Wendy Carlos, known for her work with Stanley Kubrick on the scores of films like Clockwork Orange and The Shining. Carlos met Moog in 1964 at a conference for the Audio Engineering Society and had the chance to investigate one of his early modular synths. “It was a perfect fit,” she says, “he was a creative engineer who spoke music: I was a musician who spoke science. It felt like a meeting of simpatico minds.”

Carlos helped Moog develop his designs, he helped her find her voice, the fuzzy, buzzing, droning, humming sound of an analog synth, which somehow made a perfect fit for selections from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier and Two-Part Inventions. When Carlos released Switched on Bach, her first studio album, it was “an immediate success,” as Moog himself said. “We witnessed the birth of a new genre of music”—fully synthesized keyboard music, without any acoustic instruments involved whatsoever. The Moog proved itself, and Carlos impressed both pop fans and the classical community, many of whom fully embraced the phenomenon.

A recording of Switched on Bach premiered at Carnegie Hall, Leonard Bernstein presented an arrangement of Bach’s “Little” Fugue in G minor arranged for Moog, organ, and orchestra at one of his Young People’s Concerts, and no less a Bach authority than Glenn Gould praised the album, noting that it had “made electronic music mainstream” even as it introduced entire new audiences to Bach. Carlos has since preserved her mystique through intense personal privacy and strict control of her copyright. You’ll find precious little of her music on the internet: a snippet here and there, but no Switched on Bach streaming online.

It is well worth paying for the pleasure (I’d recommend doing so by tracking down an original vinyl pressing.) Carlos released a follow-up the next year, The Well-Tempered Synthesizer, then another interpretation of Switched on Bach for the album’s 25th anniversary. This year it turns 50. You can celebrate not only by listening to the original, but checking out its equally majestic follow-up albums, the Special Edition Box Set, and a recent “spiritual successor” to Carlos’ original, Craig Leon’s 2015 Bach to Moog, a re-interpretation of Bach using the very same synthesizer Carlos did those many years ago. Almost.

The System 55, the collection of large, clunky banks of patch bays, oscillators, filters, envelopes, etc. that Carlos used, was reissued three years ago. In the short documentary above, you can see producer and composer Leon talk about Carlos’ contributions to modern, and classical, music and his own hybrid use of the early synthesizer with midi and a string section. He demonstrates how radically the distinctive Moog sound can be shaped by its wonky dials and switches, but also how it can subtly color the sound of other instruments without imposing itself. Such a revolutionary instrument required a truly revolutionary album to announce it to the world.

Related Content:

Hear Seven Hours of Women Making Electronic Music (1938- 2014)

The History of Electronic Music in 476 Tracks (1937–2001)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply