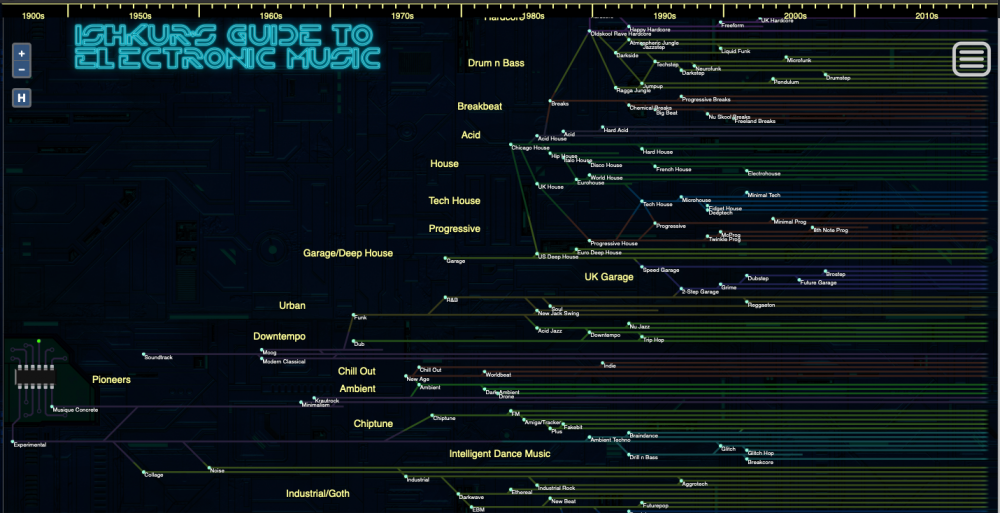

In a very short span of time, the descriptor “electronic music” has come to sound as overly broad as “classical.” But where what we (often incorrectly) call classical developed over hundreds of years, electronic music proliferated into hundreds of fractal forms in only decades. A far steeper quality curve may have to do with the ease of its creation, but it’s also a factor of this accelerated evolution.

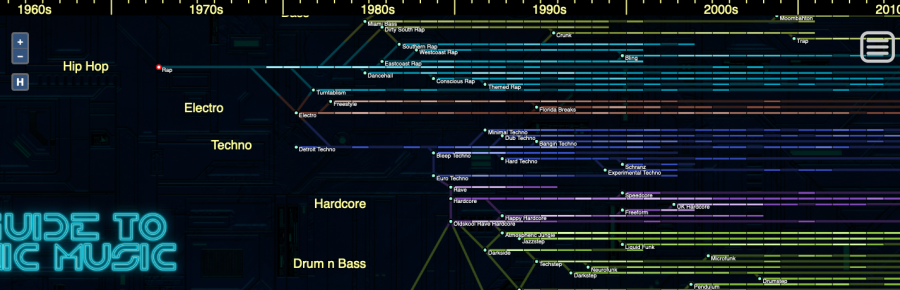

Music made by machines has transformed since its early 20th-century beginnings from obscure avant-garde experiments to massively popular genres of global dance and pop. This proliferation, notes Ishkur—designer of Ishkur’s Guide to Electronic Music—hasn’t always been to the good. Take what he calls “trendwhoring,” a phenomenon that spawns dozens of new works and subgenera in short order, though it’s arguable whether many of them should exist.

Ishkur, describes this process below in an excerpt from his erudite, sardonic “Frequently Unasked Questions”:

If fart noises were suddenly popular, each scene would trendwhore it with fartstep, fartcore, techfart, farthouse, fart trance, etc. It is especially noticeable in classic tracks that are remixed into modern genres, which some might consider sacreligious. A good example is the Dream Trance hit Robert Miles — Children, in which there is now a Hardstyle version, a Dutch House version, a McProg version, a Eurotrance version, a Goa Trance version, and even a Snap version and a shitty Brostep version. None of these genres existed when the original song came out in 1995.

Viciously irreverent tone and completist attention to detail are typical throughout this encyclopedia, an interactive Flash flowchart that chronicles the development of 100s of genres, subgenres, microgenres, etc., with streaming musical examples of every one. It’s a deeply researched, and continually expanding project first created by Ishkur, aka Kenneth John Taylor, in 1999. In 2003, Taylor updated and expanded the project and moved it to its current location. He has continuously updated it since then.

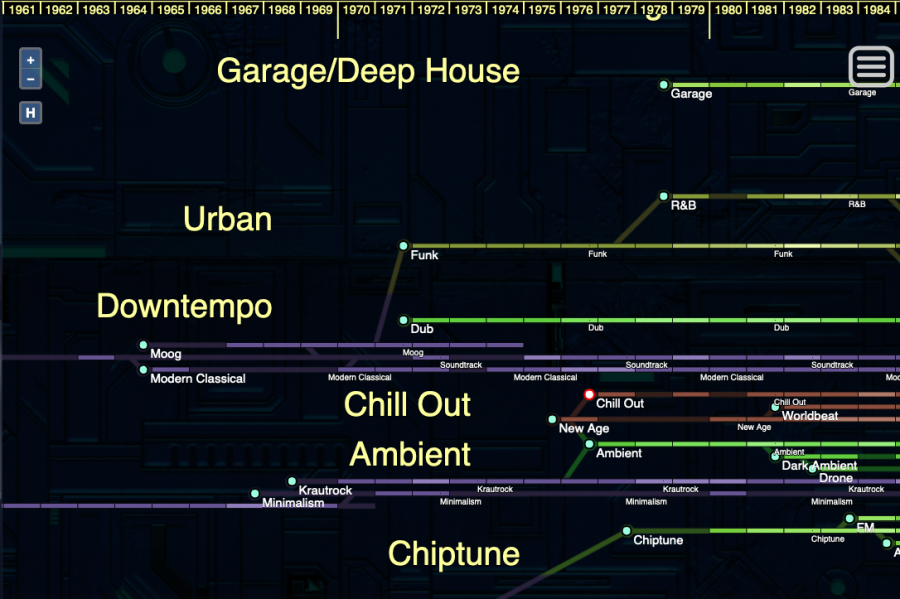

The recorded examples on Taylor’s timeline currently span around 80 years, from 1937 to 2019—a tiny drop in the great ocean of musical history. Nonetheless, the music shows how rich and complex electronic music history truly is, despite its potential—as its developmental speed (and tempos) increased—to produce disposable, derivative compositions as much as chart-burning classics and innovative, mind-expanding creative work.

As you zoom into the chart and click on the dots next to each genre, you’ll have the option to pull up Taylor’s witty guides, as informative as they are unsparingly critical. He explains “Chill Out,” for example, as a grab-bag term for electronic easy listening that “goes down easy like a fresh glass of cool lemonade or lightly sprinkled vanilla sundae…. Not only did it appeal to post-comedown party kids but their moms too, as heard in movie soundtracks, advertisement jingles, or played over the radio while shopping at the market.”

Does he approve of any forms of electronic music? Obviously. No one would spend this much time and effort and amass “30 years of back issues of Electronic Music and Keyboard magazine” and “an ungodly number of books” on a subject they despised. It’s just that he’s… well, a purist, you might say. Any media, for example, of any kind, that “uses the acronym ‘EDM,’” he writes “is complete donkey balls and should not be relied on as a source for anything.” He’s also ambitiously comprehensive, including Hip Hop and all of its variants in the mix, a move most historians of electronic music do not make, for fear of getting it wrong, perhaps, or because of cultural biases and narrow ideas about what electronic music is.

The data visualization crossed with extensive pop musicology crossed with an almost quaint kind of ultra-nerdy online snark has something for everyone. But don’t call it art, as one interviewer did. “I feel uneasy about this,” Ishkur answered. “It’s a joke more than anything. Very funny. Very silly. I poke fun at a lot of genres. It’s meant to be entertainment.” This is the standard internet disclaimer, but if you follow the guide’s branching streams through hundreds of expanding genres and scenes, you might just find you’ve become a serious student of electronic music yourself, while learning not to take any of it too seriously.

Ishkur’s guide has recently been updated for 2019. He’s also released a “15 hour DJ set of electronic music,” he announced on Twitter, “spanning several eras and a wide range of genres, all mixed in that inimitable Ishkur style.” Get the mix here.

Related Content:

The History of Electronic Music in 476 Tracks (1937–2001)

Hear Seven Hours of Women Making Electronic Music (1938–2014)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply