“The timeworn image of cloistered nuns as escapists, spurned lovers or naïve waifs has little basis in reality today,” wrote Julia Lieblich in a 1983 New York Times article, “The Cloistered Life.” “It takes more than a botched-up love affair to lure educated women in their 20’s and 30’s to the cloister in the 1980’s.”

The devotion that drew women to cloistered life in the fast-paced 80s, or today, also drew women in the middle ages. But in those days, an education was much harder to come by. Many women became nuns because no other opportunities were available. “Convent offerings,” Eudie Pak explains at History.com, “included reading and writing in Latin, arithmetic, grammar, music, morals, rhetoric, geometry and astronomy.” Other pursuits included “spinning, weaving and embroidery,” particularly among more affluent nuns.

Those “from lesser means were expected to do more arduous labor as part of their religious life.” Who knows what kinds of hardships 14th century Benedictine English nun Joan of Leeds endured while at St. Clement priory in York? The tedium alone may have driven her over the edge. Nor do we know why she first entered the convent—whether driven by faith, a desire for self-improvement, a “botched-up love affair,” or a less-than-voluntary commitment.

We know almost nothing of Joan’s life, except that at some time in 1318, she faked her death, left behind a fake body to bury, and escaped the convent to pursue what William Melton, then Archbishop of York, called “the way of carnal lust.” Joan’s sisters aided in her great escape, as the archbishop wrote in a letter: “numerous of her accomplices, evildoers, with malice aforethought, crafted a dummy in the likeness of her body in order to mislead the devoted faithful.”

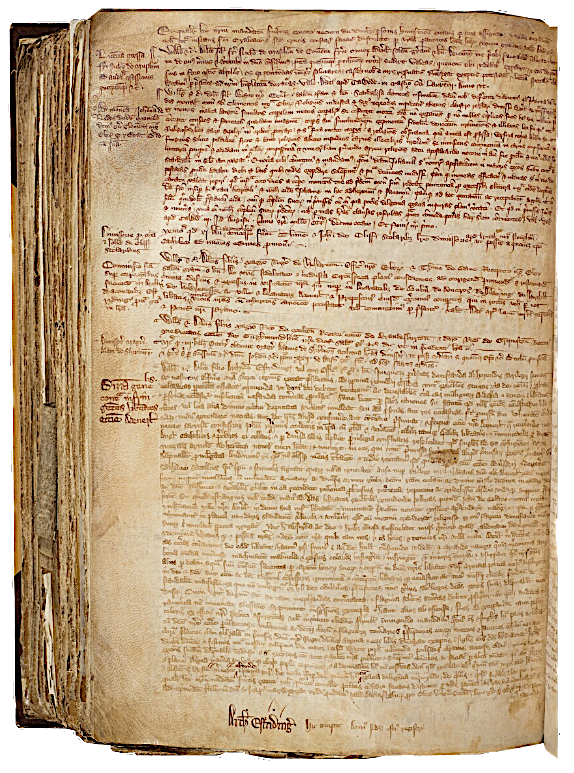

The episode—or what we know of it from Melton’s register—struck University of York professor Sarah Rees Jones as “extraordinary—like a Monty Python sketch.” Joan’s story has become a highlight of The Northern Way, a project that “seeks to assess and analyze the political roles of the Archbishops of York over the period 1306–1406.” A number of records from the period have been digitized, including William Melton’s registry, in which Joan’s escape appears (see the page of scribal notes above).

One of the archbishop’s roles involved interceding in such cases of runaway monks and nuns. “Unfortunately,” Rees Jones remarks, “we don’t know the outcome of the case” of Joan. Often, as one might expect, escapes like hers—though few as picaresque—had to do with “not wanting to be celibate…. Many of the people would have been committed to a religious house when they were in their teens, and then they didn’t all take to the religious life.”

The archbishop put matters rather less charitably: “Having turned her back on decency and the good of religion,” he writes, “seduced by indecency, she involved herself irreverently and perverted her path of life arrogantly to the way of carnal lust and away from poverty and obedience, and, having broken her vows and discarded the religious habit, she now wanders at large to the notorious peril to her soul and to the scandal of all of her order.”

Or, as we might say today, she was ready to embark on a new life path. So desperately ready, it seems, that we might only hope Joan of Leeds remained “at large” and found happiness elsewhere. Learn more about The Northern Way project here.

Related Content:

Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

One of the reasons I love history is that I learn, whether fact or speculation, kernels of information the peak my interest and make me wonder about what really happened. As in the book I just read titled “Pope Joan.” The only female pope, who, despite some evidence, the church fails to acknowledge. Thank you for the interesting article.

It’s possible that nun Joan of Leeds, born about 1295, is none other than Joan Rawson — wife (legal or not) of Ralph Rawson, Bishop of Bath and Wells (born 1309), mother of Robert (?) Rawson I.