The phrase “history is written by the victors” is a cliché, which means that it is at least half true; official histories are, to a significant degree “written,” or dictated, by ruling elites. But as far as the actual writing down, and excavating, narrating, arguing about, and revising of history goes… well, that is the work of historians, who may work for powerful institutions but who are not themselves—with several notable exceptions, of course—politicians, generals, or captains of industry.

This is all to the good. Historians, and Twitterstorians, can tell stories and present evidence that the victors might rather see disappear. And they can tell stories we never knew that we were missing, but which humanize the past by restoring the lives of ordinary people with ordinary concerns. Stories of everyday ancient Romans and Egyptians, for example, or of ancient Romans in Egypt, visiting and vandalizing the pyramids.

In one such poignant story, circulating on Twitter, a Roman woman named Terentia carved into the limestone facing of the Great Pyramid sometime around 120 AD a touching poem for her brother, who had just recently died. As told by medievalist, linguist, and Senior Editor at History Today Dr. Kate Wiles, the poem might have been lost to the ages had it not been discovered by German pilgrim Wilhelm von Boldensele in 1335.

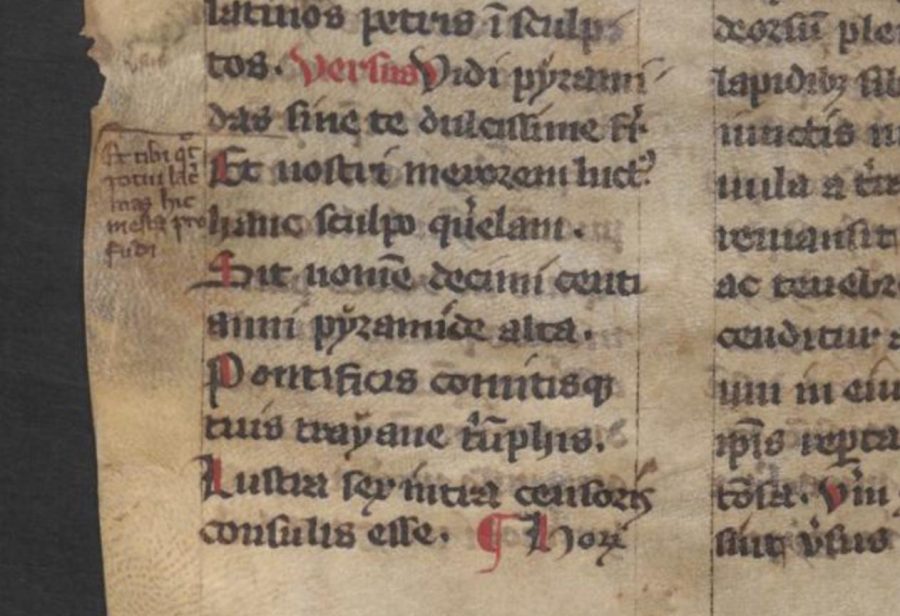

Knowing Latin, Von Boldensele read the poem, found it moving, and copied it down. (See his manuscript at the top.) Wiles quotes a part of the prose English translation:

I saw the pyramids without you, my dearest brother, and here I sadly shed tears for you, which is all I could do. And I inscribe this lament in memory of our grief. May thus be clearly visible on the high pyramid the name of Decimus Gentianus….

We can surmise that Terentia must have had some means to travel, but in Wiles’ abridged Twitter version of the story, we also might assume she could be anyone at all, grieving the loss of a close relative. Terentia’s grief is no less moving or real when we learn that the inscription goes for on several lines Wiles cut for brevity.

Turning to Emily Ann Hemelrijk’s book Matrona Docta: Educated Women in the Roman Elite from Cornelia to Julia Domna, Dr. Wiles’ source for the Great Pyramid poem, we find that Terentia wasn’t just an educated, upper class woman, she was a very well-connected one. The inscription goes on to identify her brother as “a pontifex and companion to your triumphs, Trajan, and both censor and consul before his thirtieth year of age.”

In his anthology Women Writers of Ancient Greece and Rome, Ian Michael Plant provides even more historical context. Of Terentia, we know little to nothing save the Von Boldensele’s copy of her six hexameters (and possibly more that he ignored). Of Decimus Gentianus, however, we know that he not only served as a consul under Trajan but also as governor of Macedonia under Hadrian. Terentia “chose the pyramid for her epitaph to provide a suitably grand and everlasting site for her tribute to him,” writes Plant. (Cue Shelly’s “Ozymandias.”)

Not only is the poem about a victor, but it appears to shift its address from him to the ultimate victor, Emperor Trajan, in its final lines. Should this change our appreciation of the story as a slice of Roman tourist life and example of ancient women’s writing? No, but it shows us something about what history gets preserved and why. Despite historians’ best efforts, especially in public-facing work, to make the past more accessible and relatable, they, too, are limited by what other cultures chose to preserve and what to pass over.

Hemelrijk admits, “the poem is no literary masterpiece,” but Von Boldersele saw enough merit in its sentiments to record it for posterity. He also made a judgment about the inscription’s historical import, given its references, which is probably the reason we have it today.

via Dr. Kate Wiles

Related Content:

Play Caesar: Travel Ancient Rome with Stanford’s Interactive Map

How the Egyptian Pyramids Were Built: A New Theory in 3D Animation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply