As a tourist in England, one may be persuaded to pick a piece of merchandise with the now-ubiquitous slogan “Keep Calm and Carry On,” from a little-displayed World War II motivational poster rediscovered in 2000 and turned into the 21st-century’s most cheeky emblem of stiff-upper-lip-ness. Travel across the Channel, however, and you’ll find another version of the sentiment, drawn not from war memorabilia but the ancient warning of memento mori.

“Keep Calm and Remember You Will Die” say magnets, key chains, and other souvenirs emblazoned with the logo of the Paris Catacombs, a major tourist attraction that sells timed tickets “to manage the large queue that forms daily outside the nondescript entrance on the Place Denfert-Rochereau (formerly called the Place d’Enfer, or Hell Square),” writes Allison Meier at Public Domain Review. Still profoundly creepy, the Catacombs were once as forbidding to descend into as their walls of skulls and bones are to gaze upon, requiring visitors to carry flaming torches into their depths.

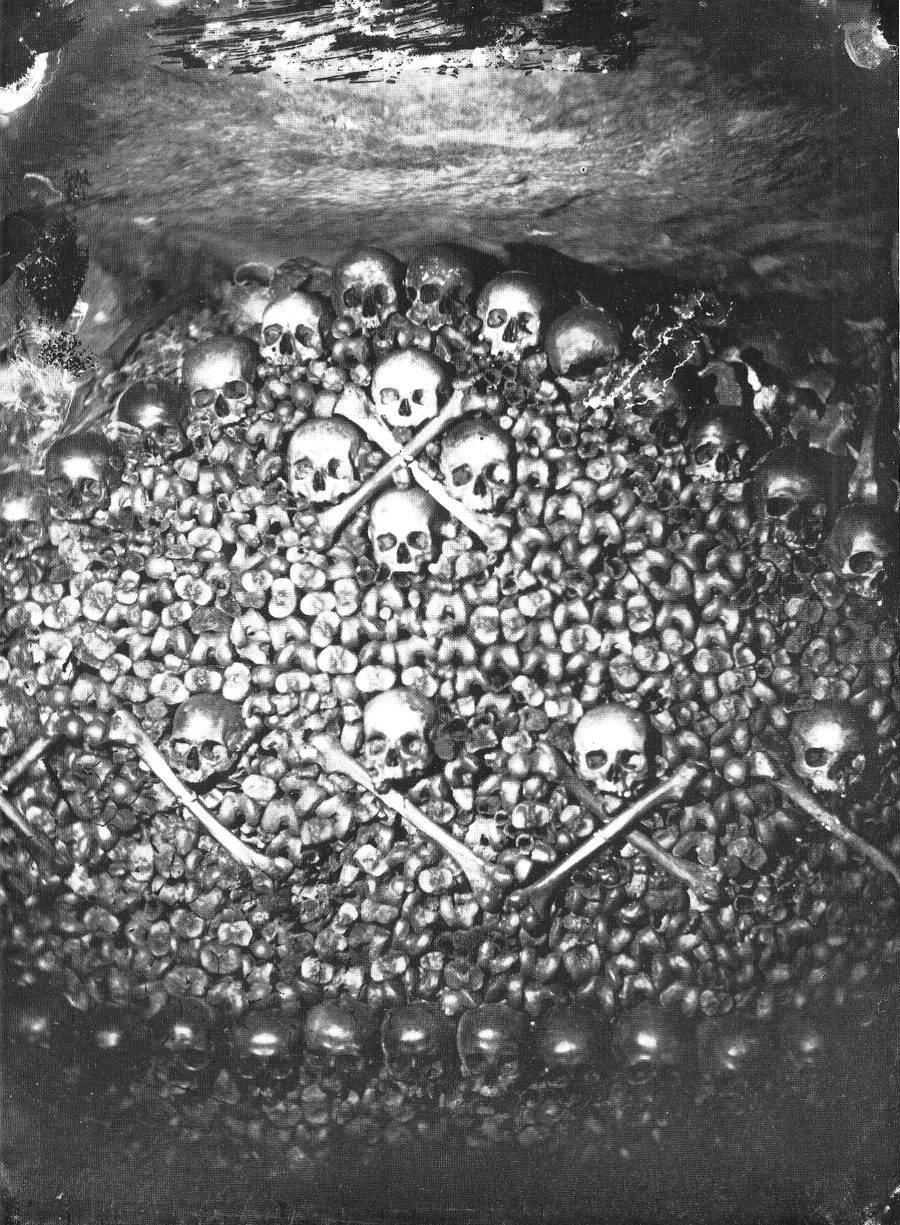

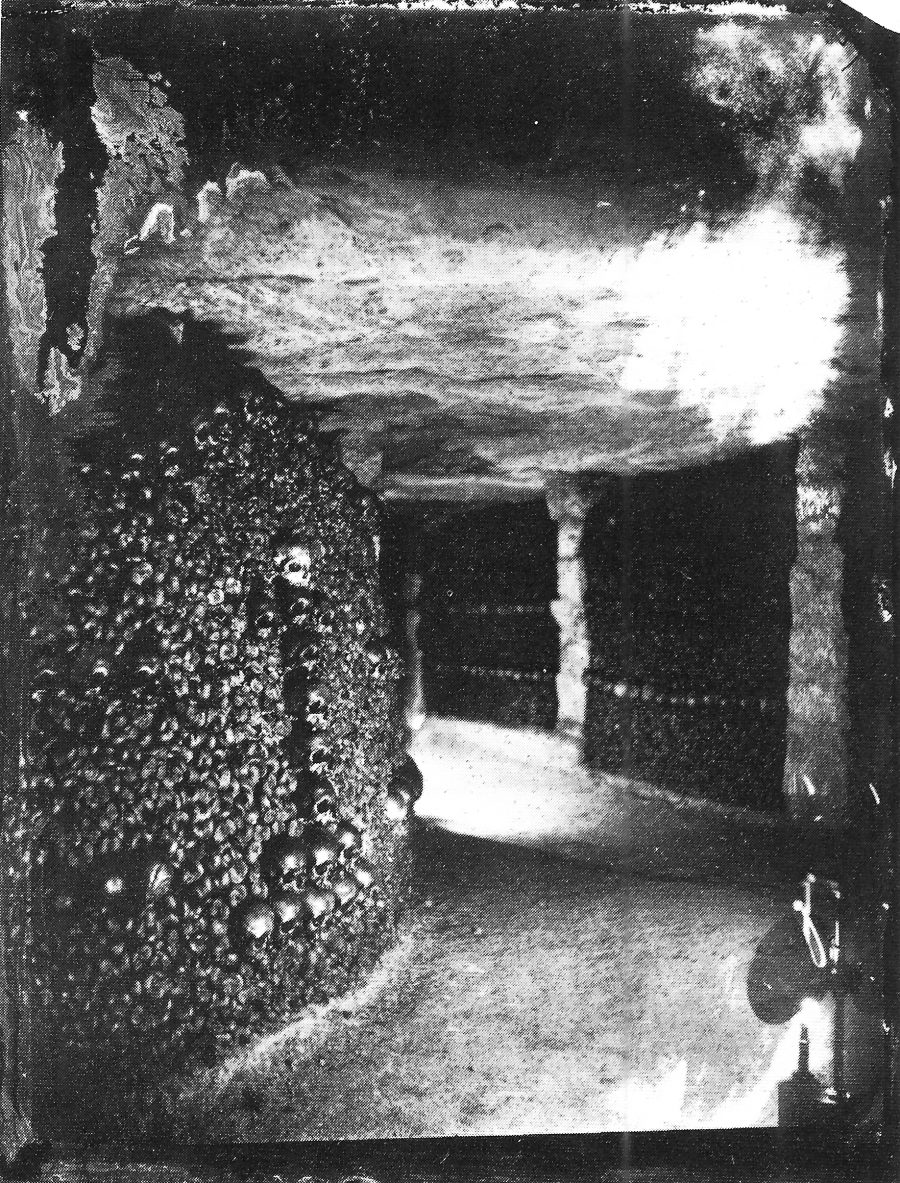

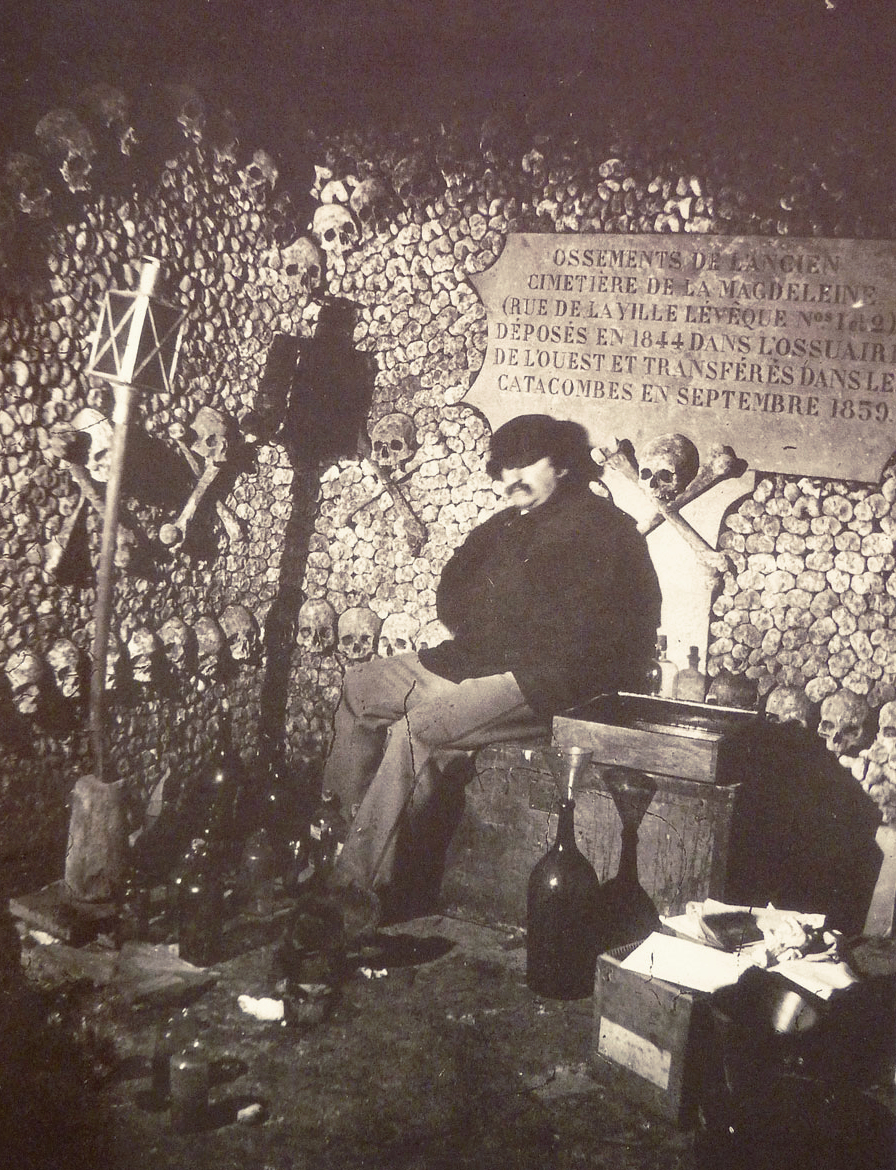

When pioneering photographer Félix Nadar “descended into this ‘empire of death’ in the 1860s artificial lighting was still in its infancy.” Using Bunsen batteries “and a good deal of patience,” Nadar captured the Catacombs as they had never been seen. He also documented the completion of “artistic facades” of skulls and long bones, built “to hide piles of other bones,” notes Strange Remains, from an estimated six million corpses exhumed from overcrowded Parisian cemeteries in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Nadar (the pseudonym of Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, born 1820), helped turn the Catacombs into the globally famous destination they became. His “subterranean photographs,” writes Matthew Gandy in The Fabric of Space: Water, Modernity, and the Urban Imagination, “played a key role in fostering the growing popularity of sewers and catacombs among middle-class Parisians, and from the 1867 Exposition onward the city authorities began offering public tours of underground Paris.” The Catacombs became, in Nadar’s own words, “one of those places that everyone wants to see and no one wants to see again.”

Visitors came seeking the grim fascinations they had seen in Nadar’s photos, taken during a “single three-month campaign,” Meier notes, sometime in 1861, after the photographer “pioneered new approaches to artificial light.” The project was an irresistible photographic essay on the leveling force of mortality. In an essay titled “Paris Above and Below,” published in the 1867 Exposition guide, Nadar described the “egalitarian confusion of death,” in which “a Merovingian king remains in eternal silence next to those massacred in September ’92.”

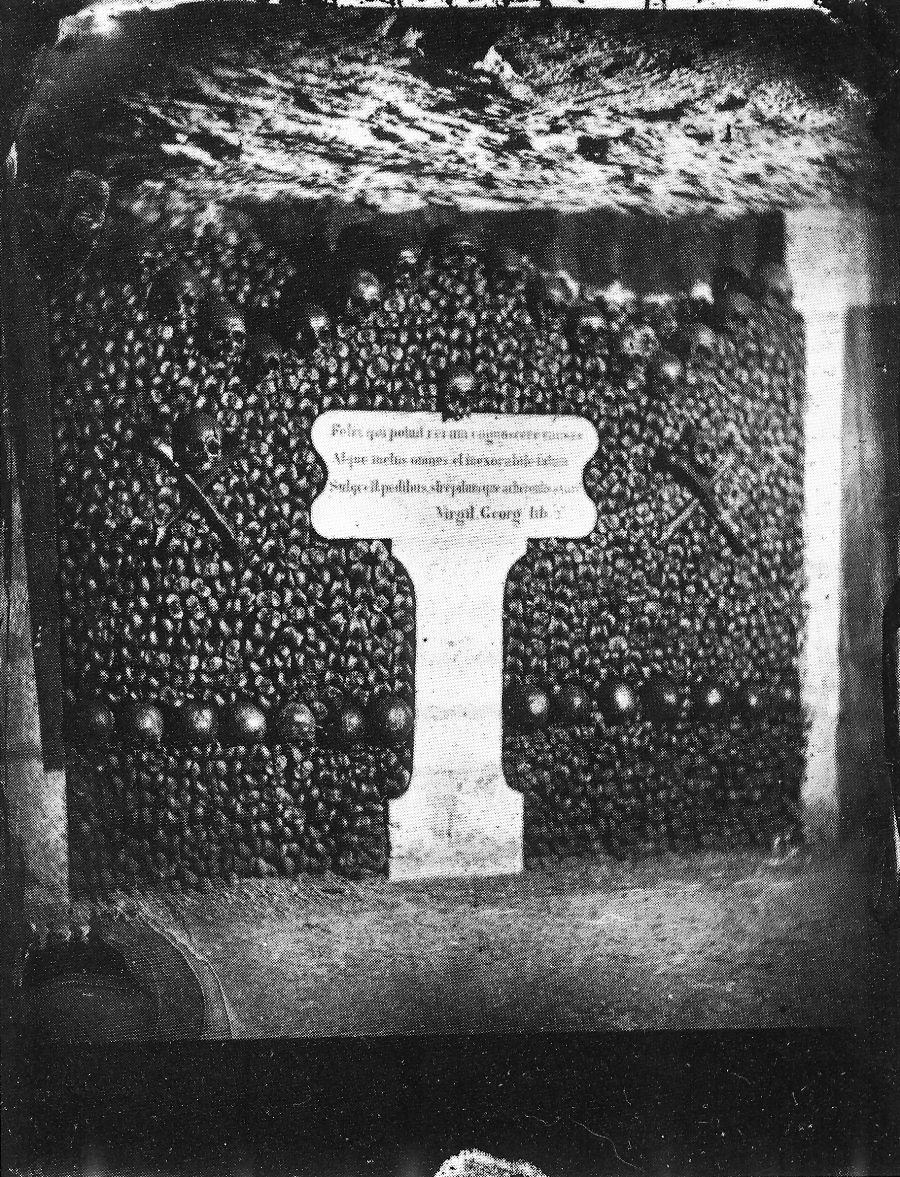

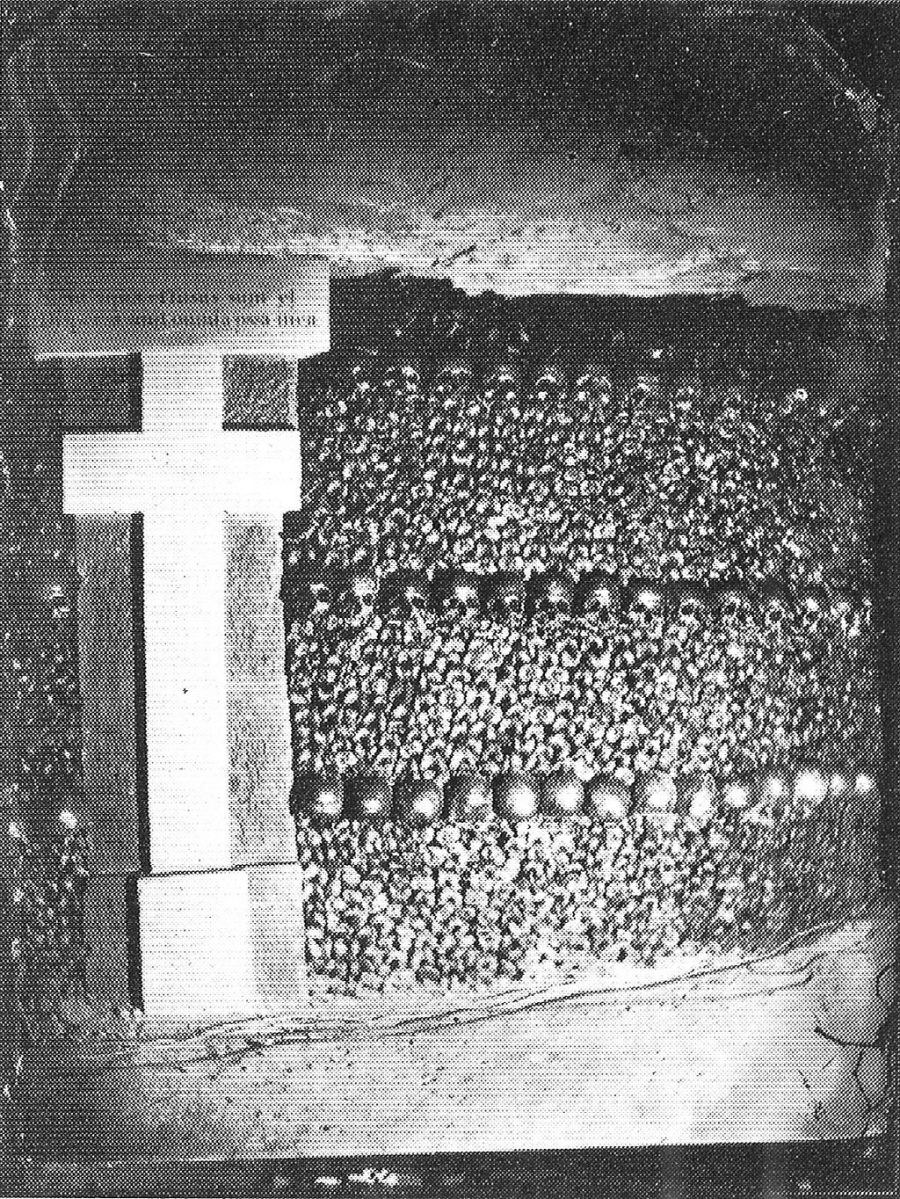

The ancient and the modern dead, peasants, aristocrats, victims of the Revolutionary terror all piled together, “every trace implacably lost in the unaccountable clutter of the most humble, the anonymous.” The huge necropolis initially had no shape or order. Its 19th century redesign reflected that of the Parisian streets above. In 1810, Napoleon authorized quarries inspector Héricart de Thury to undertake a renovation that accounted for what Thury called “the intimate rapport that will surely exist between the Catacombs and the events of the French Revolution.”

This “rapport” not only included the “mass burial of the victims of the 1792 September Massacres” Nadar references in his essay, but also, Meier points out, the arrangement of bones in “patterns, rows, and crosses; altars and columns were installed below the earth. Plaques with evocative quotations were added to encourage visitors to reflect on mortality.” Because of the long exposure times the photographs required, Nadar used mannequins to stand in for the living workers who completed this work. The only living body he captured was his own, in the self-portrait above.

Learn more about the history of the Catacombs and Nadar’s now-legendary photographic project at Public Domain Review and see many more memento mori images here.

Related Content:

Notre Dame Captured in an Early Photograph, 1838

Take a Visual Journey Through 181 Years of Street Photography (1838–2019)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply