Most U.S. readers come to know Evelyn Waugh as the “serious” writer of the saga Brideshead Revisited (and inspirer of the 1981 miniseries adaptation). This was also the case in 1954, when Charles Rolo wrote in the pages of The Atlantic that the novel “sold many more copies in the United States than all of Waugh’s other books put together.” Yet “among the literary,” Waugh’s name evokes “a singular brand of comic genius… a riotously anarchic cosmos, in which only the outrageous can happen—and when it does happen is outrageously diverting.”

The comic Waugh’s imagination “runs to… appalling and macabre inventions,” incorporating a “lunatic logic.” The sources of that imagination now reside at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, who hold Waugh’s manuscripts and 3,500-volume library.

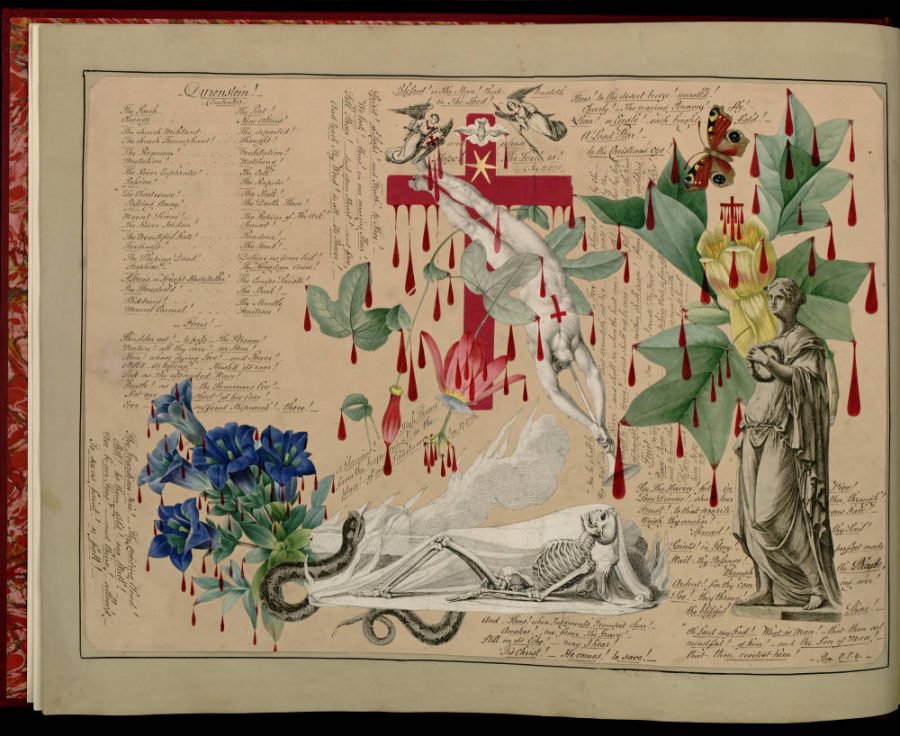

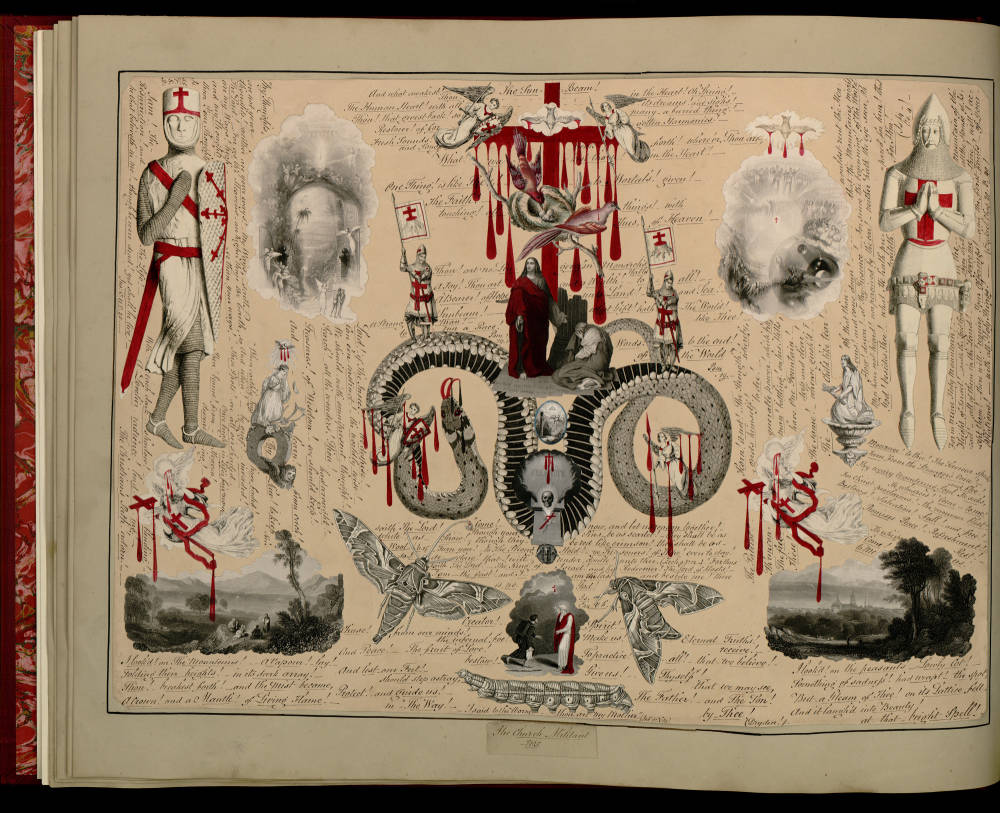

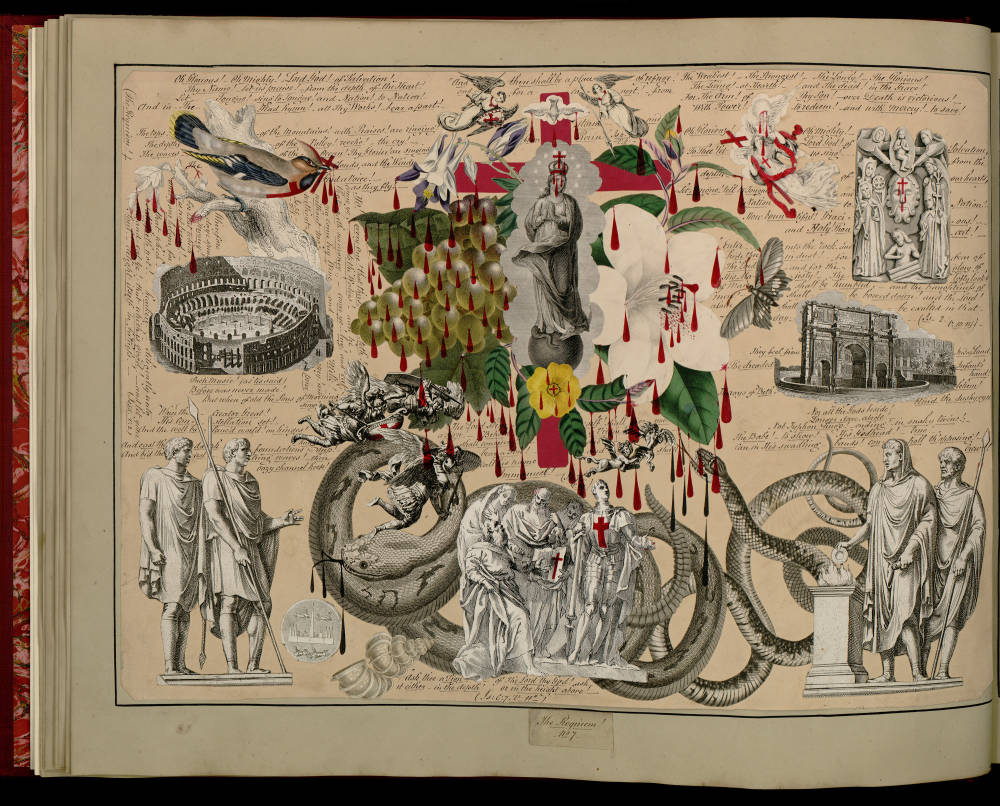

The novelist, the Ransom Center notes, “was an inveterate collector of things Victorian (and well ahead of most of his contemporaries in this regard). Undoubtedly the single most curious object in the entire library is a large oblong folio decoupage book, often referred to as the ‘Victorian Blood Book.’”

Waugh deeply admired Victorian art, and especially “those nineteenth-century enemies of technology, the Pre-Raphaelites,” writes Rolo. Still, like us, he may have looked upon scrapbooks like these as bizarre and morbidly humorous, if also possessed by an unsettling beauty. (One 2008 catalogue described them as “weird” and “rather elegant but very scary.”) More than anything, they resemble the kind of thing a goth teenager raised on Monty Python and Emily Dickinson might put together in her bedroom late at night. Such an artist would be carrying on a long “cherished tradition.”

“Victorian scrapbooking,” the Ransom Center writes, “was almost exclusively the province of women,” a way of organizing information, although “the esthetic aspect” could sometimes be “secondary.” The “Victorian Blood Book,” however, is the work of a paterfamilias named John Bingley Garland, “a prosperous Victorian businessman who moved to Newfoundland, went on to become speaker of its first Parliament, and returned to Stone Cottage in Dorset to end his days.”

Inscribed to Bingley’s daughter Amy on September 1, 1854, the book seems to have been a wedding present, made with serious devotional intent:

How does one “read” such an enigmatic object? We understandably find elements of the grotesque and surreal. But our eyes view it differently from Victorian ones. As Garland’s descendants have written, “our family doesn’t refer to…‘the Blood Book;’ we refer to it as ‘Amy’s Gift’ and in no way see it as anything other than a precious reminder of the love of family and Our Lord.”

The “Blood Book“ ‘s actual title appears to have been Durenstein!, which is the Austrian castle where Richard the Lionhearted was imprisoned. Assembled from hundreds of engravings, many by William Blake, it apparently depicts “the spiritual battles encountered by Christians along the path of life and the ‘blood’ to Christian sacrifice.” The “blood” is red India ink. The quotations surrounding each collage, according to the Garland family “are encouraging one to turn to God as our Saviour.”

One can imagine the “serious” Waugh looking on this strange object with almost reverential affection. He lapsed into a highly affected, reactionary nostalgia in his later period, announcing himself “two hundred years” behind the times. One contemporary declared, “He grows more old-fashioned every day.” But the savagely comic Waugh would not have been able to approach such a bizarre piece of folk collage art without an eye toward its use as material for his own “appalling and macabre inventions.”

See a full scanned copy of the “Victorian Blood Book,” and download high-resolution images, online at the University of Texas, Austin’s Harry Ransom Center.

Related Content:

Browse The Magical Worlds of Harry Houdini’s Scrapbooks

A Witty Dictionary of Victorian Slang (1909)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply