The Venus de Milo is one of art’s most widely recognized female forms.

The Mona Lisa may be the first stop on many Louvre visitors’ agendas, but Venus, by virtue of being unclothed, sculptural, and prominently displayed, lends herself beautifully to all manner of souvenirs, both respectful and profane.

Delacroix, Magritte, Dali, and The Simpsons have all paid tribute, ensuring her continued renown.

Renoir is that rare bird who was impervious to her 6’7” charms, describing her as the “big gendarme.” His own Venus, sculpted with the help of an assistant nearly 100 years after the Venus de Milo joined the Louvre’s collection, appears much meatier throughout the hip and thigh region. Her celebrity cannot hold a candle to that of her armless sister.

In the Vox Almanac episode above, host Phil Edwards delves into the Venus de Milo’s appeal, taking a less delirious approach than sculptor Auguste Rodin, who rhapsodized:

…thou, thou art alive, and thy thoughts are the thoughts of a woman, not of some strange, superior being, artificial and imaginary. Thou art made of truth alone, outside of which there is neither strength nor beauty. It is thy sincerity to nature which makes thee all powerful, because nature appeals to all men. Thou art the familiar companion, the woman that each believes he knows, but that no man has ever understood, the wisest not more than the simple. Who understands the trees? Who can comprehend the light?

Edwards opts instead for a Sharpie and a tiny 3‑D printed model, which he marks up like a plastic surgeon, drawing viewers’ attention to the missing bits.

The arms, we know.

Also her earlobes, most likely removed by looters eager to make off with her jewelry.

One of her massive marble feet (a man’s size 15) is missing.

And so is a portion of the plinth on which she once stood.

Interestingly, the plinth was among the items discovered by accident on the Greek island of Milos in 1820, along with two pillars topped with busts of Hercules and Hermes, the bisected Venus, and assorted marble fragments, including — maybe — an upper arm and hand holding a round object (a golden apple, mayhaps?)

Edwards doesn’t delve into the conflicting accounts surrounding the wheres and whys of this discovery. Nor does he go into the complications of the sculpture’s acquisition, and how it very nearly wound up on a ship bound for Constantinople.

What he’s most interested in is that plinth, which would have given the lie to the long-standing assertion that the Venus de Milo was created in the Classical era.

This incorrect designation made the Louvre’s newest resident a most welcome replacement for the loot France had been compelled to return to the Vatican in the wake of Napoleon’s first abdication.

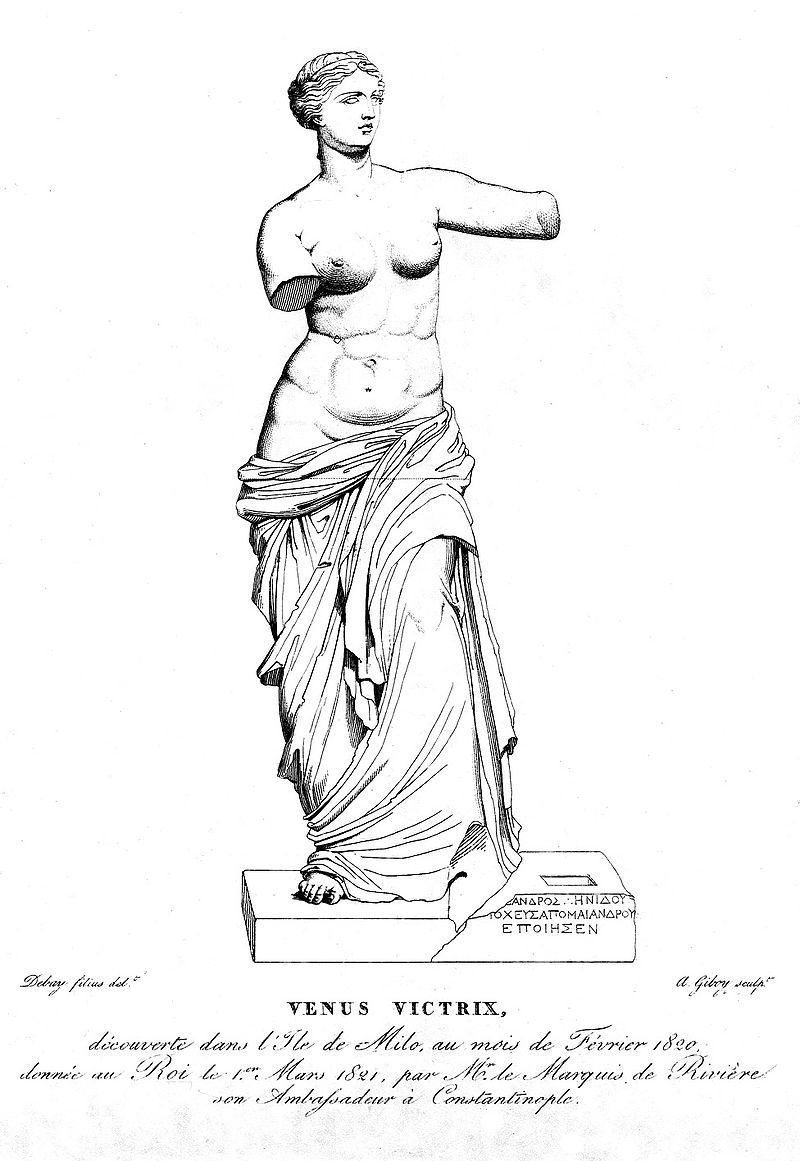

The plinth may have been “lost” under mysterious circumstances, but its inscription was preserved in a sketch by A. Debay, whose father had been a student of Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon’s now-banished First Painter, a Neo-Classicist.

(David’s final painting, Mars Disarmed by Venus and the Three Graces, completed a couple of years after Venus de Milo was installed in the Louvre, was considered a bust.)

Debay’s faithful recreation of the plinth’s inscription as part of his study of the Venus de Milo offers clues as to her creator — “ …andros son of …enides citizen of …ioch at Meander made.”

It also dates her creation to 150–50 BCE, corroborating notes French naval officer Jules d’Urville had made in Greece weeks after the discovery.

The birth of this Venus should have been attributed to the Hellenistic, not Classical period.

This would have been problematic for both France and the Louvre, as art historian Jane Ursula Harris writes in The Believer:

Had her true author been known, she likely would’ve been locked away in the museum’s archive, if not sold off. Hellenistic art had by then been denigrated by Renaissance scholars who re-conceived it in anti-classical terms, finding in its expressive, experimental form and emotional content a provocative realism that defied everything their era stood for: modesty, intellect, and equanimity…It helped that the Venus de Milo possessed several classical attributes. Her strong profile, short upper lip, and smooth features, for example, were in keeping with Classical figural conventions, as was the continuous line connecting her nose and forehead. The partially-draped figure with its attenuated silhouette – which the Regency fashion of the day imitated with its empire bust-line – also recalled classical sculptures of Aphrodite, and her Roman counterpart, Venus. Yet despite all these classical identifiers, the Venus de Milo flaunted a definitive Hellenistic influence in her provocatively low-slung drapery, high waist line, and curve-enhancing contrapposto—far more sensual and exaggerated than classical ideals allowed.

It took the Louvre over a hundred years to come clean as to its star sculpture’s true provenance.

What happened to the plinth remains anyone’s guess.

The only mystery the museum’s website seems concerned with is one of identity — is she Aphrodite, goddess of beauty, or Poseidon’s wife, Amphitrite, the sea goddess worshipped on the island on which she was discovered?

For a deeper dive into the Venus de Milo’s complicated journey to the Louvre, we recommend Rachel Kousser’s article, “Creating the Past: The Venus de Milo and the Hellenistic Reception of Classical Greece,” which can be downloaded free here. Or do as Vox’s Edwards suggests and 3‑D print a tiny Venus de Milo in a decidedly non-Classical color using MyMiniFactory’s free pattern.

Related Content:

The Making of a Marble Sculpture: See Every Stage of the Process, from the Quarry to the Studio

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply