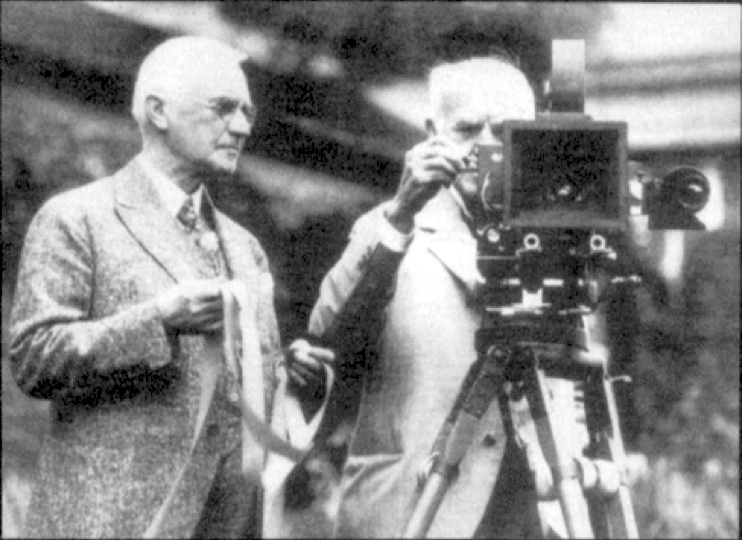

Eastman giving Edison the first roll of movie film, via Wikimedia Commons

This piece picks up where Part 1 of Peter Kaufman’s article left off yesterday…

The epistemological nightmare we seem to be in, bombarded over our screens and speakers with so many moving-image messages per day, false and true, is at least in part due to the paralysis that we – scholars, journalists, and regulators, but also producers and consumers – are still exhibiting over how to anchor facts and truths and commonly accepted narratives in this seemingly most ephemeral of media. When you write a scientific paper, you cite the evidence to support your claims using notes and bibliographies visible to your readers. When you publish an article in a magazine or a journal or a book, you present your sources – and now when these are online often enough live links will take you there. But there is, as yet, no fully formed apparatus for how to cite sources within the online videos and television programs that have taken over our lives – no Chicago Manual of Style, no Associated Press Stylebook, no video Elements of Style. There is also no agreement on how to cite the moving image itself as a source in these other, older types of media.

The Moving Image: A User’s Manual, published by the MIT Press on February 25, 2025, looks to make some better sense of this new medium as it starts to inherit the mantle that print has been wearing for almost six hundred years. The book presents 34 QR codes that resolve to examples of iconic moving-image media, among them Abraham Zapruder’s film of the Kennedy assassination (1963); America’s poet laureate Ada Límon reading her work on Zoom; the first-ever YouTube video shot by some of the company founders at the San Francisco Zoo in 2005; Darnella Frazier’s video of George Floyd’s murder; Richard Feynman’s physics lectures at Cornell; courseware videos from MIT, Columbia, and Yale; PBS documentaries on race and music; Wikileaks footage of America at war; January 6 footage of the 2021 insurrection; interviews with Holocaust survivors; films and clips from films by and interviews with Sergei Eisenstein, John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, François Truffaut and others; footage of deep fake videos; and the video billboards on the screens now all over New York’s Times Square. The electronic edition takes you to their source platforms — YouTube, Vimeo, Wikipedia, the Internet Archive, others — at the click of a link. The videos that you can play facilitate deep-dive discussions about how to interrogate and authenticate the facts (and untruths!) in and around them.

At a time when Trump dismisses the director of our National Archives and the Orwellian putsch against memory by the most powerful men in the world begins in full force, is it not essential to equip ourselves with proper methods for being able to cite truths and prove lies more easily in what is now the medium of record? How essential will it become, in the face of systematic efforts of erasure, to protect the evidence of criminal human depravity – the record of Nazi concentration camps shot by U.S. and U.K. and Russian filmmakers; footage of war crimes, including our own from Wikileaks; video of the January 6th insurrection and attacks at the American Capitol – even as political leaders try to scrub it all and pretend it never happened? We have to learn not only how to watch and process these audiovisual materials, and how to keep this canon of media available to generations, but how to footnote dialogue recorded, say, in a combat gunship over Baghdad in our histories of American foreign policy, police bodycam footage from Minneapolis in our journalism about civil rights, and security camera footage of insurrectionists planning an attack on our Capitol in our books about the United States. And how should we cite within a documentary a music source or a local news clip in ways that the viewer can click on or visit?

Just like footnotes and embedded sources and bibliographies do for readable print, we have to develop an entire systematic apparatus for citation and verification for the moving image, to future-proof these truths.

* * *

At the very start of the 20th century, the early filmmaker D. W. Griffith had not yet prophesied his own vision of the film library:

Imagine a public library of the near future, for instance, there will be long rows of boxes or pillars, properly classified and indexed, of course. At each box a push button and before each box a seat. Suppose you wish to “read up” on a certain episode in Napoleon’s life. Instead of consulting all the authorities, wading laboriously through a host of books, and ending bewildered, without a clear idea of exactly what did happen and confused at every point by conflicting opinions about what did happen, you will merely seat yourself at a properly adjusted window, in a scientifically prepared room, press the button, and actually see what happened.

No one yet had said, as people would a century later, that video will become the new vernacular. But as radio and film quickly began to show their influence, some of our smartest critics began to sense their influence. In 1934, the art historian Erwin Panofsky, yet to write his major works on Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer, could deliver a talk at Princeton and say:

Whether we like it or not, it is the movies that mold, more than any other single force, the opinions, the taste, the language, the dress, the behavior, and even the physical appearance of a public comprising more than 60 per cent of the population of the earth. If all the serious lyrical poets, composers, painters and sculptors were forced by law to stop their activities, a rather small fraction of the general public would become aware of the fact and a still smaller fraction would seriously regret it. If the same thing were to happen with the movies, the social consequences would be catastrophic.

And in 1935, media scholars like Rudolf Arnheim and Walter Benjamin, alert to the darkening forces of politics in Europe, would begin to notice the strange and sometimes nefarious power of the moving image to shape political power itself. Benjamin would write in exile from Hitler’s Germany:

The crisis of democracies can be understood as a crisis in the conditions governing the public presentation of politicians. Democracies [used to] exhibit the politician directly, in person, before elected representatives. The parliament is his public. But innovations in recording equipment now enable the speaker to be heard by an unlimited number of people while he is speaking, and to be seen by an unlimited number shortly afterward. This means that priority is given to presenting the politician before the recording equipment. […] This results in a new form of selection—selection before an apparatus—from which the champion, the star, and the dictator emerge as victors.

At this current moment of champions and stars – and dictators again – it’s time for us to understand the power of video better and more deeply. Indeed, part of the reason that we sense such epistemic chaos, mayhem, disorder in our world today may be that we haven’t come to terms with the fact of video’s primacy. We are still relying on print as if it were, in a word, the last word, and suffering through life in the absence of citation and bibliographic mechanisms and sorting indices for the one medium that is governing more and more of our information ecosystem every day. Look at the home page of any news source and of our leading publishers. Not just MIT from its pole position producing video knowledge through MIT OpenCourseWare, but all knowledge institutions, and many if not most journals and radio stations feature video front and center now. We are living at a moment when authors, publishers, journalists, scholars, students, corporations, knowledge institutions, and the public are involving more video in their self-expression. Yet like 1906, before the Chicago Manual, or 1919 before Strunk’s little guidebook, we have had no published guidelines for conversing about the bigger picture, no statement about the importance of the moving-image world we are building, and no collective approach to understanding the medium more systematically and from all sides. We are transforming at the modern pace that print exploded in the sixteenth century, but still without the apparatus to grapple with it that we developed, again for print, in the early twentieth.

* * *

Public access to knowledge always faces barriers that are easy for us to see, but also many that are invisible. Video is maturing now as a field. Could we say that it’s still young? That it still needs to be saved – constantly saved – from commercial forces encroaching upon it that, if left unregulated, could soon strip it of any remaining mandate to serve society? Could we say that we need to save ourselves, in fact, from “surrendering,” as Marshall McLuhan wrote some 60 years ago now, “our senses and nervous systems to the private manipulation of those who would try to benefit from taking a lease on our eyes and ears and nerves, [such that] we don’t really have any rights left”? Before we have irrevocably and permanently “leased our central nervous systems to various corporations”?

You bet we can say it, and we should. For most of the 130 years of the moving image, its producers and controllers have been elites—and way too often they’ve attempted with their control of the medium to make us think what they want us to think. We’ve been scared over most of these years into believing that the moving image rightfully belongs under the purview of large private or state interests, that the screen is something that others should control. That’s just nonsense. Unlike the early pioneers of print, their successors who formulated copyright law, and their successors who’ve gotten us into a world where so much print knowledge is under the control of so few, we – in the age of video – can study centuries of squandered opportunities for freeing knowledge, centuries of mistakes, scores of hotfooted missteps and wrong turns, and learn from them. Once we understand that there are other options, other roads not taken, we can begin to imagine that a very different media system is – was and is – eminently possible. As one of our great media historians has written, “[T]he American media system’s development was the direct result of political struggle that involved suppressing those who agitated for creating less market-dominated media institutions. . . . [That this] current commercial media system is contingent on past repression calls into question its very legitimacy.”

The moving image is likely to facilitate the most extraordinary advances ever in education, scholarly communication, and knowledge dissemination. Imagine what will happen once we realize the promise of artificial intelligence to generate mass quantities of scholarly video about knowledge – video summaries by experts and machines of every book and article ever written and of every movie and TV program ever produced.

We just have to make sure we get there. We had better think as a collective how to climb out of what journalist Hanna Rosin calls this “epistemic chasm of cuckoo.” And it doesn’t help – although it might help our sense of urgency – that the American president has turned the White House Oval Office into a television studio. Recall that Trump ended his February meeting with Volodymyr Zelenskyy by saying to all the cameras there, “This’ll make great television.”

The Moving Image: A User’s Manual exists for all these reasons, and it addresses these challenges. And these challenges have everything to do with the general epistemic chaos we find ourselves in, with so many people believing anything and so much out there that is untrue. We have to solve for it.

As the poets like to say, the only way out is through.

–Peter B. Kaufman works at MIT Open Learning. He is the author of The New Enlightenment and the Fight to Free Knowledge and founder of Intelligent Television, a video production company that works with cultural and educational institutions around the world. His new book, The Moving Image: A User’s Manual, is just out from the MIT Press.

Leave a Reply