Public libraries are unsung heroes of their communities. Many a busy working adult can take their importance for granted. But parents of young children know—the library is a quiet haven, place of wonder and discovery, and free resource for all sorts of educational experiences. Given the importance of libraries in kids’ lives, it’s no wonder that six of the top ten most-checked-out books—according to the New York Public Library—are children’s books.

The NYPL calculated the most checked out books in its history in honor of its 125th anniversary. Given that it houses the second largest collection in the U.S., after the Library of Congress, and serves millions in the most linguistically diverse city in the country, its circulation numbers give us a reasonable sampling of near-universal tastes.

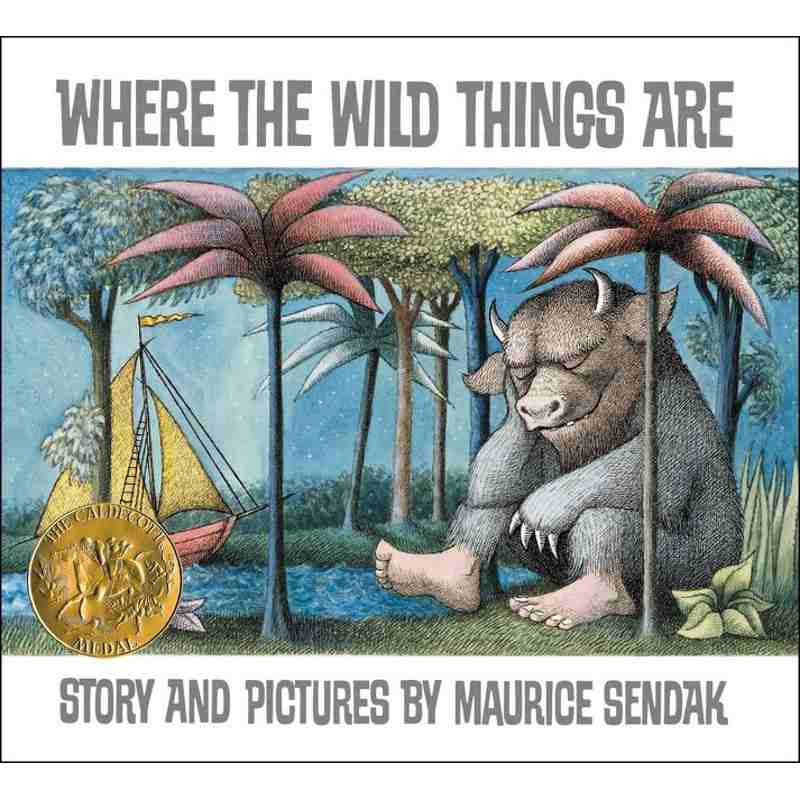

These include timeless classics of children’s literature: Ezra Jack Keats’ Caldecott-winning The Snowy Day tops the list, “in print and in the Library’s catalog continuously since 1962”; The Cat in the Hat comes in at a close second. Where the Wild Things Are and The Very Hungry Caterpillar round out the list of books for the very young.

Where is the stalwart Goodnight Moon, you may ask? Here we have a juicy bit of lore:

By all measures, this book should be a top checkout (in fact, it might be the top checkout) if not for an odd piece of history: extremely influential New York Public Library children’s librarian Anne Carroll Moore hated Goodnight Moon when it first came out. As a result, the Library didn’t carry it until 1972. That lost time bumped the book off the top 10 list for now. But give it time.

For now, Margaret Wise Brown’s 1947 classic receives honorable mention. Classic kids’ books circulate a lot because they’re widely read, but also because they’re short, which leads to more turnover, the Library points out. Length of time in print is also a factor, which makes the presence of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, published in 1998, particularly impressive.

- The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats: 485,583 checkouts

- The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss: 469,650 checkouts

- 1984 by George Orwell: 441,770 checkouts

- Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak: 436,016 checkouts

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee: 422,912 checkouts

- Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White: 337,948 checkouts

- Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury: 316,404 checkouts

- How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie: 284,524 checkouts

- Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling: 231,022 checkouts

- The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle: 189,550 checkouts

Like J.K. Rowling’s modern classic, all of the remaining books on the list are novels—save outlier How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie—and all are novels read extensively by middle and high school students, a further sign of the significance of public libraries.

Some students may only be required to read a small handful of novels in their school career, and whether they follow through, and maybe go on to read more and more books, and maybe write a few books of their own, may depend upon those novels constantly circulating for everyone through institutions like the New York Public Library.

See the full list above and learn more about the project at NPR and the NYPL.

via Metafilter

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.