If you’ve read Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis in English, it’s likely that your translation referred to the transformed Gregor Samsa as a “cockroach,” “beetle,” or, more generally, a “gigantic insect.” These renderings of the author’s original German don’t necessarily miss the mark—Gregor scuttles, waves multiple legs about, and has some kind of an exoskeleton. His charwoman calls him a “dung beetle”… the evidence abounds. But the German words used in the first sentence of the story to describe Gregor’s new incarnation are much more mysterious, and perhaps strangely laden with metaphysical significance.

Translator Susan Bernofsky writes, “both the adjective ungeheuer (meaning “monstrous” or “huge”) and the noun Ungeziefer are negations—virtual nonentities—prefixed by un.” Ungeziefer, a term from Middle High German, describes something like “an unclean animal unfit for sacrifice,” belonging to “the class of nasty creepy-crawly things.” It suggests many types of vermin—insects, yes, but also rodents. “Kafka,” writes Bernofsky, “wanted us to see Gregor’s new body and condition with the same hazy focus with which Gregor himself discovers them.”

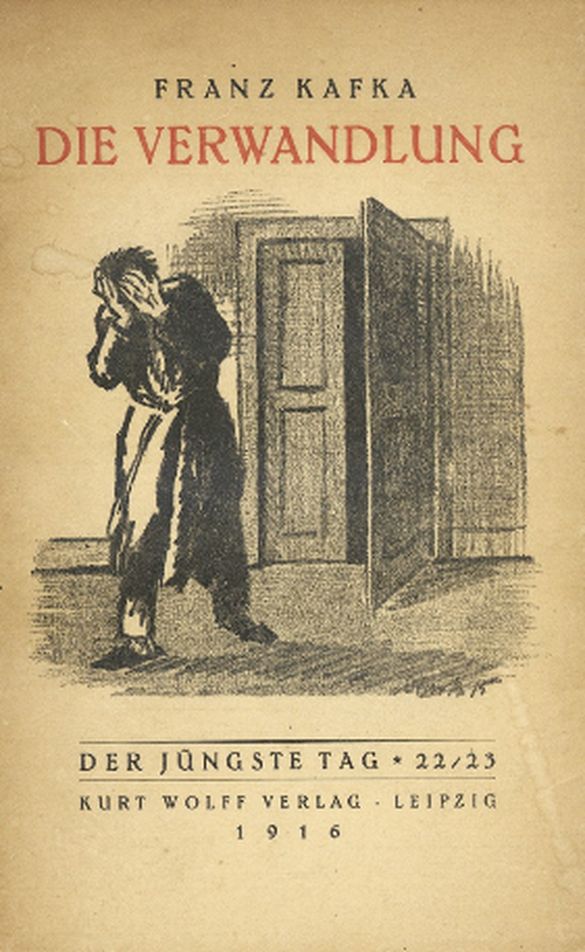

It’s likely for that very reason that Kafka prohibited images of Gregor. In a 1915 letter to his publisher, he stipulated, “the insect is not to be drawn. It is not even to be seen from a distance.” The slim book’s original cover, above, instead features a perfectly normal-looking man, distraught as though he might be imagining a terrible transformation, but not actually physically experiencing one.

Yet it seems obvious that Kafka meant Gregor to have become some kind of insect. Kafka’s letter uses the German Insekt, and when casually referring to the story-in-progress, Kafka used the word Wanze, or “bug.” Making this too clear in the prose dilutes the grotesque body horror Gregor suffers, and the story is told from his point of view—one that “mutates as the story proceeds.” So writes Dutch reader Freddie Oomkins, who further observes, “at the physical level Gregor, at different points in the story, starts to talk with a squeaking, animal-like voice, loses control of his legs, hangs from the ceiling, starts to lose his eyesight, and wants to bite his sister—not really helpful in determining his taxonomy.”

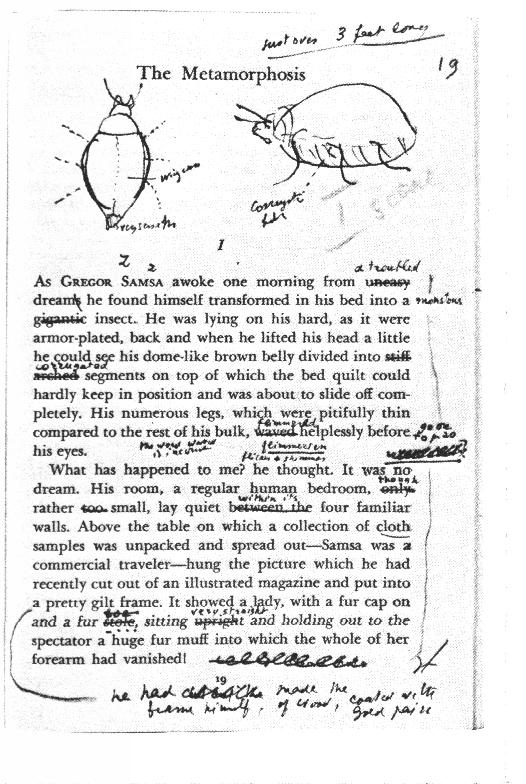

Difficulties of translation and classification aside, Russian literary mastermind and lepidopterist Vladimir Nabokov decided that he knew exactly what Gregor Samsa had turned into. And, against the author’s wishes, Nabokov even drew a picture in his teaching copy of the novella. Nabokov also heavily edited his edition, as you can see in the many corrections and revisions above. In a lecture on The Metamorphosis, he concludes that Gregor is “merely a big beetle” (notice he strikes the word “gigantic” from the text above and writes at the top “just over 3 feet long”), and furthermore one who is capable of flight, which would explain how he ends up on the ceiling.

All of this may seem highly disrespectful of The Metamorphosis’ author. Certainly Nabokov has never been a respecter of literary persons, referring to Faulkner’s work, for example, as “corncobby chronicles,” and Joyce’s Finnegans Wake as a “petrified superpun.” Yet in his lecture Nabokov calls Kafka “the greatest German writer of our time. Such poets as Rilke or such novelists as Thomas Mann are dwarfs or plastic saints in comparison with him.” Though a saint he may be, Kafka is “first of all an artist,” and Nabokov does not believe that “any religious implications can be read into Kafka’s genius.” (“I am interested here in bugs, not humbugs,” he says dismissively.)

Rejecting Kafka’s tendencies toward mysticism runs against most interpretations of his fiction. One might suspect Nabokov of seeing too much of himself in the author when he compares Kafka to Flaubert and asserts, “Kafka liked to draw his terms from the language of law and science, giving them a kind of ironic precision, with no intrusion of the author’s private sentiments.” Ungeheueres Ungeziefer, however, is not a scientific term, and its Middle German literary origins—which Kafka would have been familiar with from his studies—clearly connote religious ideas of impurity and sacrifice.

With due respect to Nabokov’s formidable erudition, it seems in this instance at least that Kafka fully intended imprecision, what Bernofsky calls “blurred perceptions of bewilderment,” in language “carefully chosen to avoid specificity.” Kafka’s art consists of this ability to exploit the ancient stratifications of language. His almost Kabbalistic treatment of signs and his aversion to graven images may consternate and bedevil translators and certain novelists, but it is also the great source of his uncanny genius.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

Hear Benedict Cumberbatch Read Kafka’s The Metamorphosis

The Art of Franz Kafka: Drawings from 1907–1917

Vladimir Nabokov (Channelled by Christopher Plummer) Teaches Kafka at Cornell

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I always assumed that the metamorphosis in Kafka’s story was not meant to be taken literally, but as a metaphorical device to show the protagonists mental anguish. A less well known story of his, but in my opinion better crafted, is The Burrow. I have thought about it often as the pandemic drags on.