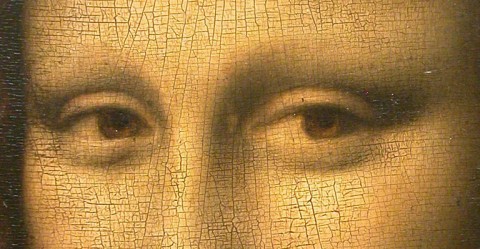

Every year, five million visitors stream into the Louvre in Paris, making it the most visited museum in the world. And, more than any other painting, visitors head to see Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, painted circa 1503 — 1519.

It’s tempting to attribute the popularity of the Mona Lisa to the enduring genius of da Vinci. But, as NPR’s All Things Considered recounts, there was a time when the painting hardly attracted public attention, and what turned the painting into an object of public adoration was something baser than genius itself: brazen theft. Click here and NPR will tell you the story of the great Mona Lisa heist that went down on August 21, 1911, almost 100 years ago…

Related Content:

A Virtual Tour of the Sistine Chapel

Google “Art Project” Brings Great Paintings & Museums to You

MoMA Puts Pollock, Rothko & de Kooning on Your iPad

Once again, the NPR Radio broadcast regarding the theft of the Mona Lisa is being promoted and unfortunately there is almost no truth to the information presented in the story.

Writer/Director Joe Medeiros has spent the last 35 years researching this story and the last four years shooting his documentary, THE MISSING PIECE: THE TRUTH ABOUT THE MAN WHO STOLE THE MONA LISA.www.monalisamissing.com

Here is the site for the press release regarding Medeiros. He is considered the leading expert in the world on the theft and Peruggia’s life story.

http://www.cisionwire.com/falco-ink/r/mona-lisa-stolen-100-years-ago–august-21–1911,c9148515

HERE ARE THE RESEARCHED VERIFIABLE FACTS THAT CORRECT NPR’S STORY:

The Louvre was not closed on a Monday because of a holiday.

It was closed every Monday for cleaning and general maintenance. (Today the Louvre is closed on a Tuesday for the same reason. We shot in the Louvre on a Tuesday and saw how few workers there were.)

Three men did not hide in a closet on Sunday night and did not exit the Louvre at 7 am.

The legend of the three men and the closet came from a 1932 article in the Saturday Evening Post written by a former Hearst journalist named Karl Decker. Decker claimed that the theft was a conspiracy to sell Mona Lisa forgeries. Three men were required to steal the painting because she weighed nearly 220 pounds. Many people have played “telephone” with this story so today it comes across as fact but it isn’t.

We have examined Decker’s story and his background extensively and believe his story to be an utter fabrication. We have also found what we believe are the articles that Decker used for his research – including one about the Mona Lisa’s weight. The Chief Scientist of the Louvre, Michel Menu, told me that the wooden panel of the Mona Lisa weighs merely 2 kilos or about 4.6 pounds. The Mona Lisa and frame including the glass can be carried by one man. In fact, Vincent Delieuvin, the Louvre curator in charge of the Mona Lisa told me that he has carried her that way himself.

One man Vincenzo Peruggia entered the Louvre on that Monday at 7 am.

He simply blended in with the other workers. There was no need to hide overnight. Because there was no real security at the time he could enter the museum with ease. He was familiar with the Louvre because he had worked there.

He was dressed in a workman’s smock which painters and workers of the day often wore. He was out of the Louvre 30–40 minutes later. A shop clerk named Andre Bouquet who was on his way to work saw a man carrying a wrapped “package” under his arm throw something into a little ditch next to the Louvre. It was a doorknob from an interior door that Peruggia had removed, thinking he could exit the museum through that door. Bouquet couldn’t give a good description of Peruggia because he was across the street and behind Peruggia.

The Mona Lisa was not in a glass case

The Mona Lisa and 1600 other paintings were put behind glass because of recent vandalism to several of the masterpieces. (It was a huge undertaking, more than the 2 Louvre framers could handle. A company named Gobier who did the glazing work at the Louvre was brought in to help. Because he was a trusted worker with the company, Peruggia was one of 5 men assigned to cut and clean the glass He worked November 1909 to January 1910 and again from November 1910 to January 1911. He became very knowledgeable of the ins and outs of the museum.

There was no large bulge in anyone’s jacket and it wasn’t covered with a blanket.

Although considered a small painting, the Mona Lisa is approximately 21x30 inches. Peruggia was 5’3”. The painting would be too large to stuff under a coat or a smock. (I tried it with a replica of the painting my daughter who is Peruggia’s height.) Peruggia had no blanket with him. Why did he need to? He simply took off his smock and wrapped it around the painting. The blanket story comes from a newspaper article where someone saw a man carrying something under a blanket and boarding a train. The man was later found. It wasn’t Peruggia and he didn’t have the Mona Lisa.

Two years in a trunk

Peruggia says he built the trunk in the winter of 1911. So for the first few months, he said it was hidden on a table in his room covered by a cloth or in his 6x6 closet, turned to the wall so it looked like a piece of wood. One can assume it was there in the closet in November 1911 when an Inspector of the Surete came to Peruggia’s room to question him.

Peruggia also admitted giving the painting to his friend Vincenzo Lancellotti to hold for 6 weeks. Vincenzo Lancellotti and his brother Michele are often cited as Peruggia’s accomplices. Although Peruggia said he did tell Lancellotti of his intention to take the painting and he did show, and then give it to Lancellotti afterwards, Lancellotti denied involvement. The Lancellottis were arrested but subsequently released without charges.

We interviewed the nephew of Michele Lancellotti in Italy. He tells a completely different story which is entertaining but not backed by any proof. This story is in my film.

Picasso was not arrested

His good friend, the poet Apollinaire was arrested. Picasso was merely questioned because he, unknowingly, had stolen statues from the Louvre in his possession. Apollinaire spent 8 days in jail.

Peruggia tried to sell the painting and an expert from a local gallery was called in to examine it

Peruggia did admit he wanted to be compensated for returning the painting to Italy and the record does show that he did have money in mind. The expert from the “local gallery” was Giovanni Poggi, the Director of the Uffizi – Florence’s famous art museum. Peruggia wanted the Mona Lisa returned there. Poggi, the art dealer Alfredo Geri and Peruggia took the painting to the Uffizi. Poggi called his superior in Rome to come and authenticate the painting. Once it was, Peruggia was arrested the next day.

This groundbreaking documentary will right 100 years of erroneous history and for the first time present both an historically accurate presentation about the facts surrounding the theft and Vincenzo Peruggia’s life story. Medeiros has examined over 1,500 primary source documents to establish the truth about Peruggia and the greatest little known art crime in history. He also has the last interview every given by Peruggia’s only daughter, Celestina Peruggia. Medeiros went to see her to learn about her father, but discovered she knew less about him that he did. He died at her feet when she was a toddler. She gave Medeiros her blessing to bring her the truth about her fathers life and his unthinkable theft. At the end of the film, Peruggia’s true motives are revealed to both Celestina and the world. Celestina Peruggia passed away in March 2011, but she is resting in peace knowing the truth about her father will finally be told in Medeiros’ documentary, THE MISSING PIECE.

I suggest you contact Guy Raz and NPR to let them know they are presenting FALSE, SENSATIONALIZED HISTORY. For such an esteemed news outlet, it is disheartening to know they did not check their facts before airing this story.

Respectfully,

Justine Medeiros

Executive Producer,

The Missing Piece

the story of the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911 is one that interests many, many people. To show your support for the True History of that event, please take down your link to the NPR story. Write a blog entry about Joe Medeiros’ documentary instead. You have been privileged to receive an early preview of the real facts presented in the film. Use them to your advantage. (I am a Senior Researcher and Translator for Joe Medeiros’ film)

Leonardo da Vinci is one of a kind and a famous painter that we have heard after his formation of Mona Lisa, it is pretty clear that over 5 million visitors in a year, this is very interesting to everyone else that his passion has exist throughout of this handiwork with Mona Lisa creation. I really want to provoke about the full story on how Mona Lisa paint has been swoop.

http://www.lespressesdureel.com/EN/ouvrage.php?id=3503&menu=

Does Mona Lisa deserve her mustache? An erudite review of 180 pre- and post-Duchamp caricatures and misappropriations.

Linguist, semiotician and art historian, Marc Décimo is Senior Lecturer in French Linguistics at the University of Orléans and Regent of the College of ‘Pataphysics (Chair of Literary, Ethnographical and Architectural Amoriography). He is the editor of Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor’s memories with Marcel Duchamp, and of Brisset’s complete works. He published around twenty books on fous littéraires and historical avant-gardes, including an essay on Brisset (Jean-Pierre Brisset — Prince des Penseurs), and numerous books on Duchamp: Duchamp mis à nu (“Duchamp laid bare”), Duchamp facile (“Duchamp made easy”)…