Growing up, I didn’t think about all the individual qualities that make a great movie. I just thought of Blade Runner. Whatever Ridley Scott’s 1982 adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep had, it made for high cinematic quality indeed. As naive as it sounds, it doesn’t fall much short of modern critical and target-audience consensus. Visually, intellectually, and technically, Blade Runner has endured the decades almost effortlessly; how many other tales of humans real and artificial in a dystopian future megalopolis can you say the same about, at least with a straight face? Yet back in the early eighties, you would have had to call the picture, which opened to a weekend of only $6.15 million in ticket sales against its $28 million budget, a flop. Nor could critics come up with much praise: “A waste of time,” said Gene Siskel of Siskel & Ebert. (“I have never quite embraced Blade Runner,” Ebert wrote 25 years later, “but now it is time to cave in and admit it to the canon.”)

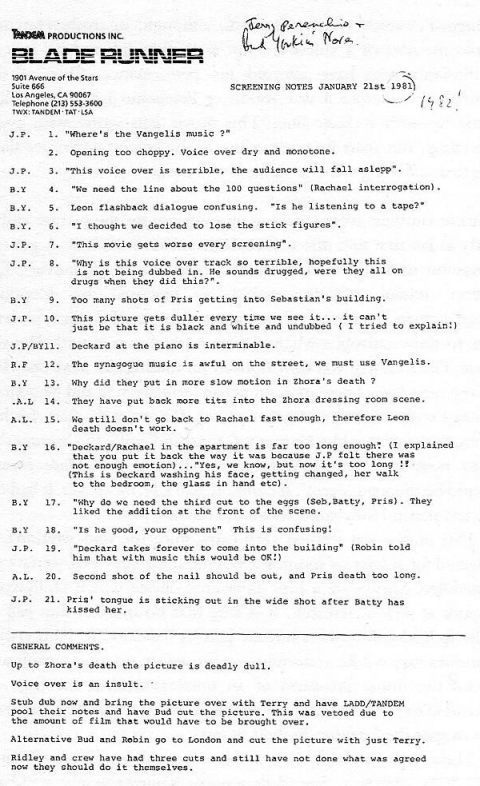

Have a look at the sheet of screening notes above (or click here to view a larger image), and you’ll find that even the studio executives didn’t like the movie. Some Blade Runner fans blame the poor initial reception on the cut that 1982’s critics and audiences saw, which differs considerably from the version so many of us revere today. They cite in particular a series of deadeningly explanatory voice-overs performed after the fact by star Harrison Ford, which sounds like a classic demand by philistine “suits” in charge until you read the notes from one executive referred to as J.P.: “Voice over dry and monotone,” “This voice over is terrible,” “Why is this voice over track so terrible.” And under “general comments”: “Voice over is an insult.” But with the offending track’s removal, the replacement of certain shots, tweaks in the plot, and the simple fullness of time, Blade Runner has gone from one of the least respected science fiction films to one of the most. Yet part of me wonders if some of those higher-ups in the screening ever made peace with it. A certain A.L., for instance, makes the fourteenth point, and adamantly: “They have to put more tits into the Zhora dressing room scene.”

via Neatorama

Related Content:

Blade Runner is a Waste of Time: Siskel & Ebert in 1982

The Blade Runner Sketchbook: The Original Art of Syd Mead and Ridley Scott Online

Blade Runner: The Final, Final Cut of the Cult Classic

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

…good to see the critics are finally onboard! I am a big Philip K. Dick fan and Scott’s adaptation of “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep” began a great run of film depictions of his work. I understand Scott and others are developing a four part BBC production of Man In the High Castle.

Sorry, but your commen on the tits comment is incorrect. It does NOT include the word “to” which changes the nature of that comment.

However, it is funny to see all the negative comments on the film which I presonally see as the number one movie of all times!

While your post is interesting, the title is at best a massive distortion. Siskel hated the film, but even Ebert’s initial review in the Chicago Sun-Times gave it three stars out of four. You even somewhat distort his later review — which is, after all, in his “Great Movies” collection — by leaving out the phrase “admiring it at arm’s length,” which occurs between “I have never quite embraced Blade Runner” and “but now it is time to cave in and admit it to the canon.” That phrase changes the point of the sentence considerably. He’s contrasting his great intellectual appreciation of the film to his somewhat more subdued emotional fondness for it.

Certainly the film’s reputation has climbed in ways almost no one would have predicted at the time, though the film we admire now is not the same one people (including me) saw then. “Blade Runner” is one of the few films in which the later director’s cuts make a truly substantive difference (probably more than any film except Lang’s “Metropolis” and Leone’s “Once Upon a Time in America,” unless someone someday finds an original cut of Welles’ “The Magnificent Ambersons”). Regardless, you don’t need the straw-man of saying everyone “originally hated” it to make your point.

When I first saw Blade Runner I was greatly disappointed. The film cut out two of the crucial elements found in the novel: Mercerism and the Buster Friendly Show. By so doing, Ridley Scott effectively excised the heart and soul of Philip K. Dick’s wonderful novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. Further, Scott moved the action from San Francisco to Los Angeles and made the android Rachael an ally rather than a betrayer. At the end of the day, Scott accomplished little more than a remake of an old Outer Limits episode called Demon With A Glass Hand, which also had to do with humanity versus robots, and was also set in the Bradbury Building. If you want to glimpse where Scott acquired the “look” of Blade Runner, check out that old TV show.