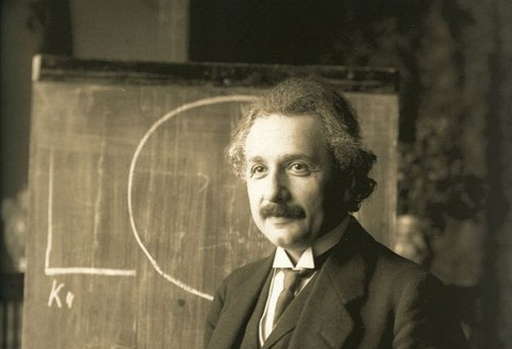

Here is a rare recording of Albert Einstein reading his speech on the immediate aftermath of World War II, “The War is Won, But the Peace is Not”:

The speech was delivered on December 10, 1945, at the Fifth Nobel Anniversary Dinner at the Hotel Astor in New York. Only four months earlier, the United States had dropped atomic bombs on civilian populations in the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Einstein didn’t work on the atomic bomb, but in 1939 he had signed a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt urging him to procure uranium and accelerate nuclear research. In his speech, Einstein draws a comparison between contemporary physicists and the founder of the Nobel Prize, who invented dynamite.

Physicists find themselves in a position not unlike that of Alfred Nobel himself. Alfred Nobel invented the most powerful explosive ever known up to his time, a means of destruction par excellence. In order to atone for this, in order to relieve his human conscience, he instituted his awards for the promotion of peace and for achievements of peace. Today, the physicists who participated in forging the most formidable and dangerous weapon of all times are harassed by an equal feeling of responsibility, not to say guilt. And we cannot desist from warning, and warning again, we cannot and should not slacken in our efforts to make the nations of the world, and especially their governments, aware of the unspeakable disaster they are certain to provoke unless they change their attitude toward each other and toward the task of shaping the future.

But Einstein says he is troubled by what he sees in the months following World War II.

The war is won, but the peace is not. The great powers, united in fighting, are now divided over the peace settlements. The world was promised freedom from fear, but in fact fear has increased tremendously since the termination of the war. The world was promised freedom from want, but large parts of the world are faced with starvation while others are living in abundance. The nations were promised liberation and justice. But we have witnessed, and are witnessing even now, the sad spectacle of “liberating” armies firing into populations who want their independence and social equality, and supporting in those countries, by force of arms, such parties and personalities as appear to be most suited to serve vested interests. Territorial questions and arguments of power, obsolete though they are, still prevail over the essential demands of common welfare and justice.

Einstein then goes on to talk about a specific case: the plight of his own people, the European Jews.

While in Europe territories are being distributed without any qualms about the wishes of the people concerned, the remainders of European Jewry, one-fifth of its prewar population, are again denied access to their haven in Palestine and left to hunger and cold and persisting hostility. There is no country, even today, that would be willing or able to offer them a place where they could live in peace and security. And the fact that many of them are still kept in the degrading conditions of concentration camps by the Allies gives sufficient evidence of the shamefulness and hopelessness of the situation.

Einstein concludes by calling for “a radical change in our whole attitude, in the entire political concept.” Without doing so, he says, “human civilization will be doomed.”

Note: The full text of “The War is Won, But the Peace is Not” is available in the Einstein anthologies Out of My Later Years and Ideas and Opinions.

Evil exists and always has. No “radical change” will eradicate it. The best that can be hoped for is that there are enough people in each generation to stand up to it.

The talk should have remained that of the atomic bomb and not be used as a vehicle for other situations that, still today, need sorting out.

The real horror of what they created has not been explained by any means sufficiently. A Nobel prize is not even a beginning of recompense for what they did and what we live with today as a constant threat from various sources and prey to the whim of those in power of some sort or other.

The world itself is at risk, the destruction of this planet is in the balance and single issues are not the topic but the all encompassing destructive force that really seems rather inevitable as the world populations war amongst themselves continually and seem unable to live lives and protect themselves, others and this planet.

Peace is for the wicked, those who rule over others with cloaks adorned. Simple men who attempt to gain peace in the world we live in find themselves tirelessly grinding the stone into a wee little pebble of truth to toss into the pond of heartache in the end. A simple man must find closure and understanding in the fact that peace is for the wicked. In times when the mind wonders the vast expanses of the human condition we must accept our current state, our less than equal value. The simple man has the power to find peace within himself, but peace in the world; only for the wicked.

gayyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyy jewwww

“In times when the mind wonders the vast expanses of the human condition we must accept our current state, our less than equal value. The simple man has the power to find peace within himself, but peace in the world; only for the wicked.”

We must accept no such thing. I and I are one. There can be nothing but equality.

“Simple men who attempt to gain peace in the world we live in find themselves…”

Einstein simple?

You’re simple. You’re wicked. They’re both just words but this is 2016 and YOU’RE THE ONE! #YOU’RETHEONE2016

If I have to decide between your grim fatalism, and Einstein’s message of, however thin, hope, I have to choose the latter. It seems more and more clear that the survival of the race is at stake, and, as a father, especially, I have to believe there is hope that it will survive. There is nothing wicked about that.

True

If you read the whole speech then you will see that the radical change he is talking about is brotherhood among the people powerful enough to control the destiny of mankind. Which is basically an encouragement of the United Nations to be good to each other first and foremost, because if things get bad between the leaders of nuclear countries, then good and evil people might be killed together by nuclear war.

People can stand up to evil, but militaries are not so much about good and evil, they are (defensively speaking) about protecting their nation whether or not that nation is mostly good or mostly evil.

A bomb doesn’t care if you are good or evil when it explodes.

Thank you very much