How do you follow up on making a children’s movie classic? If you’re Tim Burton, you spin a tale of sex, murder and conceptual art.

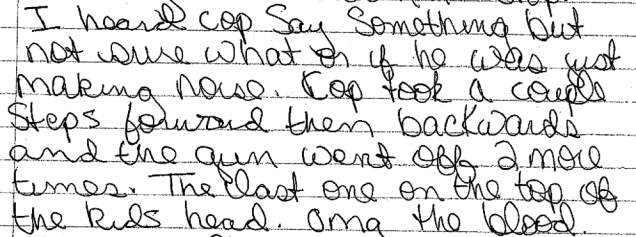

On the heels of his feature debut Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, Tim Burton adapted Ray Bradbury’s “The Jar” (1944) for an episode of the ‘80s reboot of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. In Bradbury’s story, a failing farmer buys a jar with a curious thing floating in it. It is described as “one of those pale things drifting in alcohol plasma … with its peeled, dead eyes staring out at you and never seeing you.” This thing, however, has a peculiar charisma. People come for miles to gawk at it, strangely captivated by its uncanny charm. Well, almost everyone. The farmer’s cheating wife, however, loathes it to the pit of her marrow and when she tries to get rid of it, things take a violent turn.

Burton gives the story a decidedly Reagan-era twist. Instead of being a down-and-out farmer, Knoll (played by Griffin Dunne) is a fading star of the New York art scene. The episode opens with a critic savaging Knoll’s new opening, which is filled with large, preposterous conceptual pieces. The artist flees the show and his belittling harpy of a wife in favor of the local junkyard. There, he pries the titular jar from the trunk of a 1938 Mercedes. Floating inside is what looks like a Dr. Seuss creature drown in Windex. Knoll is both fascinated and repulsed by it. So, naturally, he places it at the center of his show. The results are mixed. Sure, Knoll starts to sell art again but his wife also starts to get stabby with a kitchen knife.

The episode is delicious fun. From the eye-popping color palette to the crisp, graphic direction to the painfully ‘80s hairstyles, this work feels very much a part of the same world as Burton’s next movie, Beetlejuice. In fact, composer Danny Elfman and screenwriters Michael McDowell and Larry Wilson worked on both. You can watch it above.

Related Content:

Tim Burton’s Early Student Films

Vincent, Tim Burton’s Early Animated Film

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.