Images courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Actor George Takei was once best known as Star Trek’s Mr. Sulu. He still is, of course, but over the last couple decades his friendly, intelligent, and wickedly funny presence on social media has landed him a new popular role as a civil liberties advocate. Takei’s activist passion is informed not only by his status as a gay man, but also by his childhood experiences. At the age of 5, Takei was rounded up with his American-born parents and taken to a Japanese internment camp in Arkansas, where he would live for the next three years. In an interview with Democracy Now, Takei spoke frankly about this history:

We’re Americans…. We had nothing to do with the war. We simply happened to look like the people that bombed Pearl Harbor. But without charges, without trial, without due process—the fundamental pillar of our justice system—we were summarily rounded up, all Japanese Americans on the West Coast, where we were primarily resident, and sent off to 10 barb wire internment camps—prison camps, really, with sentry towers, machine guns pointed at us—in some of the most desolate places in this country.

Takei and his family were among over 100,000 Japanese-Americans—over half of whom were U.S. citizens—interned in such camps.

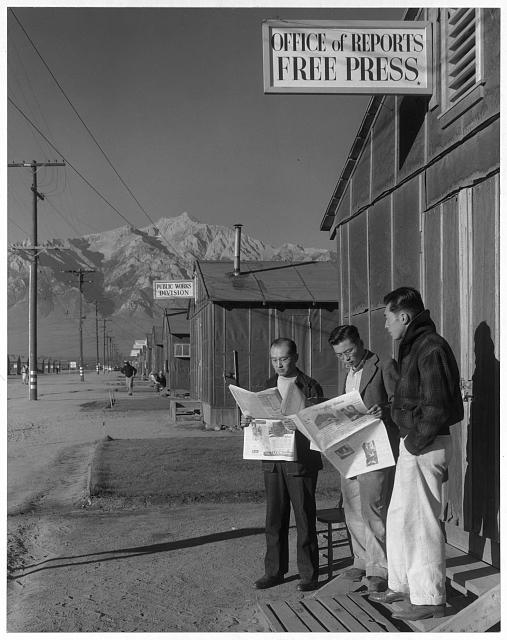

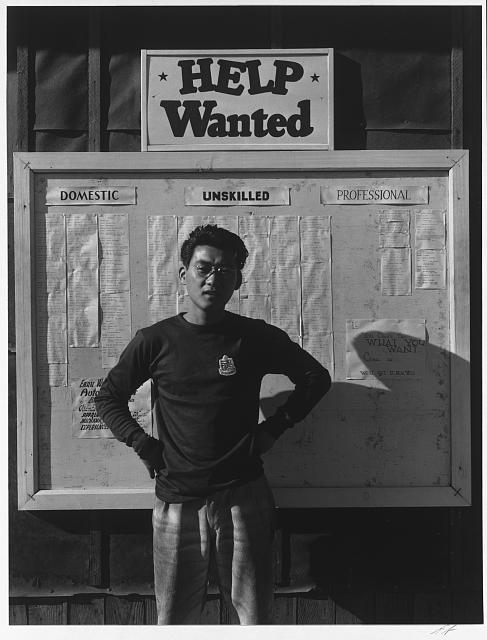

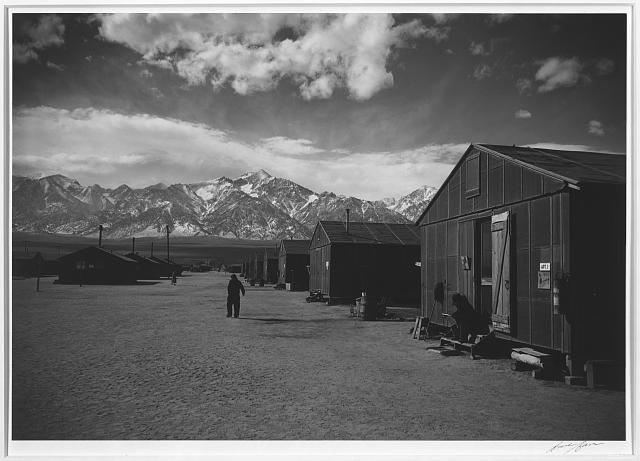

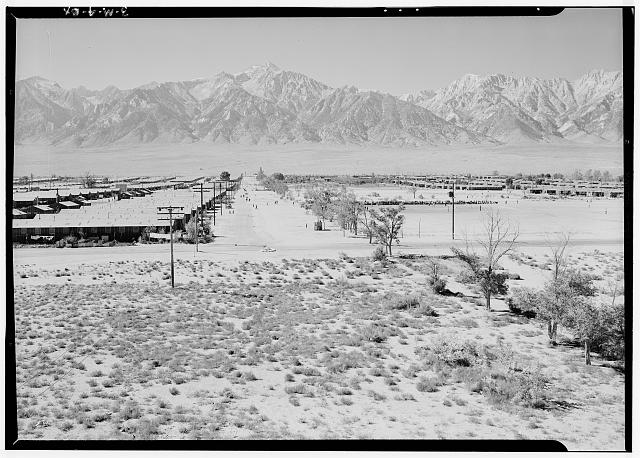

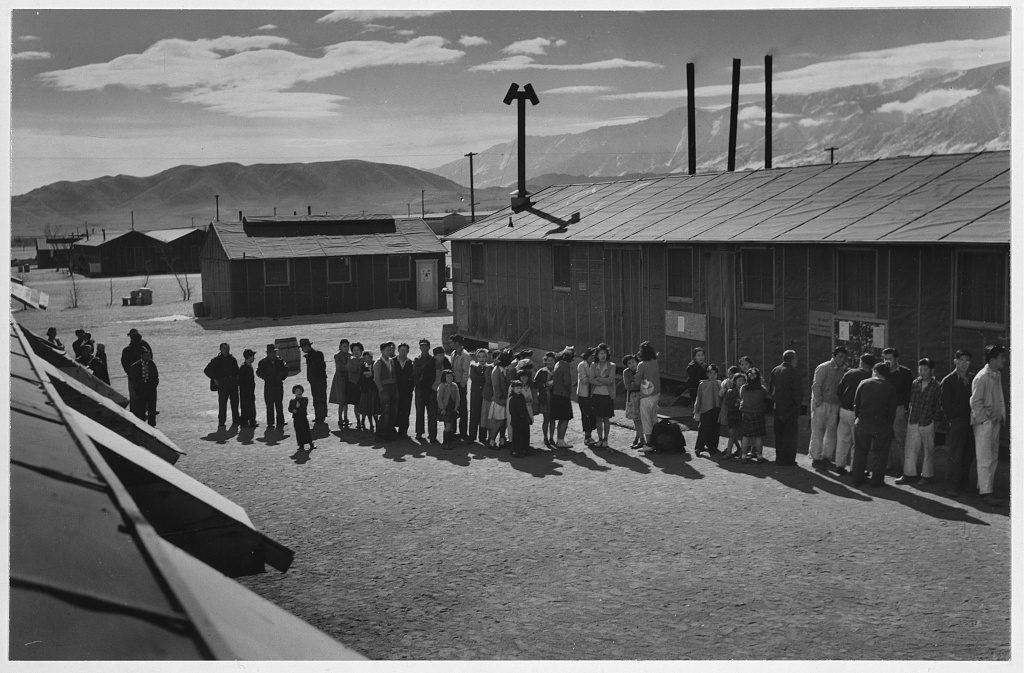

Into one of these camps, Manzanar, located in the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas, celebrated photographer Ansel Adams managed to gain entrance through his friendship with the warden. Adams took over 200 photographs of life inside the camp.

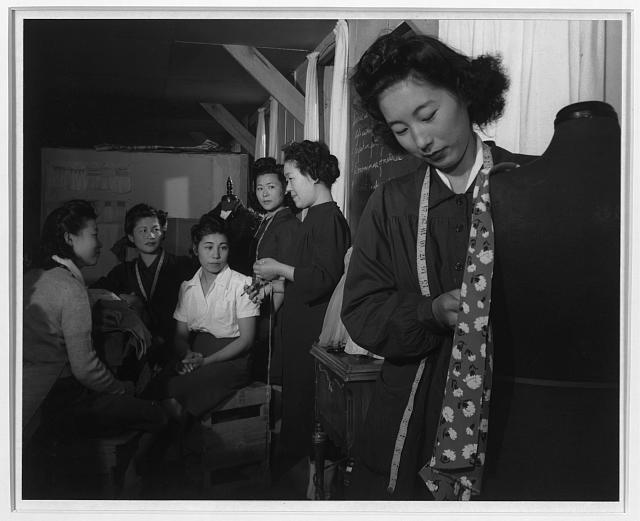

In 1965, he donated his collection to the Library of Congress, writing in a letter, “The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, business and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and dispair [sic] by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment.”

Adams had another purpose as well—as scholar of the period Frank H. Wu describes it—“to document some aspects of the internment camp that the government didn’t want to have shown.” These include “the barbed wire, and the guard towers, and the armed soldiers.” Prohibited from documenting these control mechanisms directly, the photographer “captured them in the background, in shadows,” says Wu: “In some of the photos when you look you can see just faintly that he’s taking a photo of something, but in front of the photo you can see barbed wire, or on the ground you can see the shadow of barbed wire. Some of the photos even show the blurry outline of a soldier’s shadow.”

The photographs document the daily activities of the internees—their work and leisure routines, and their struggles to maintain some semblance of normalcy while living in hastily constructed barracks in the harshest of conditions.

Though the landscape, and its climate, could be desolate and unforgiving, it was also, as Adams couldn’t help but notice, “magnificent.” The collection includes several wide shots of stretches of mountain range and sky, often with prisoners staring off longingly into the distance. But the majority of the photos are of the internees—men, women, and children, often in close-up portraits that show them looking variously hopeful, happy, saddened, and resigned.

You can view the entire collection at the Library of Congress’ online catalog. Adams also published about 65 of the photographs in a book titled Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese Americans in 1944. The collection represents an important part of Adams’ work during the period. But more importantly, it represents events in U.S. history that should never be forgotten or denied.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

Dr. Seuss’ World War II Propaganda Films: Your Job in Germany (1945) and Our Job in Japan (1946)

Ansel Adams Reveals His Creative Process in 1958 Documentary

Dr. Seuss Draws Anti-Japanese Cartoons During WWII, Then Atones with Horton Hears a Who!

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.

Leave a Reply