Some of the U.S.‘s greatest secular sages also happen to be some of its greatest cranks, contrarians, and critics. I refer to a category that includes Ambrose Bierce, H.L. Mencken, and Hunter S. Thompson. The many differences between these characters don’t eclipse a fundamental similarity: not a one embraced any of the usual pieties about the inherent, infallible greatness of Western Civilization, though each one in his own way made a significant contribution to the Western canon. We would be greatly remiss if we did not include among them perhaps the greatest American satirist of all, Mark Twain.

Twain skewered all comers, usually with such wit and invention that we smile and nod even when we feel the sting ourselves. Such was his talent, to deflate puffery in Western literature, politics, religion, and… as we will see, in art. “Throughout his career”—writes UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library—“Twain expressed his strong reactions to Western painting and sculpture, particularly the Old Masters, both in his published works and in private.” He offered up some hilariously irreverent takes on some of the most revered works of art in history: “his opinions are often passionate, sometimes eccentric, and always lively.” Take for example Twain’s tepid assessment of that most recognizable of Renaissance masterpieces, the Mona Lisa. In an unpublished draft called “The Innocents Adrift,” an account of an 1891 boat trip down the Rhone River, Twain “admitted to being puzzled by the adulation accorded” the painting.

To Twain, the Mona Lisa seemed “merely a good representation of a serene & subdued face… The complexion was bad; in fact it was not even human; there are no people of that color.” The painting’s greenish hue prompted one of Twain’s companions, possibly an invention of the author’s, to exclaim in response, “that smoked haddock!” “After some discussion,” write the UC Berkeley librarians, “the travelers concede that it requires a ‘trained eye’ to appreciate certain aspects of art.” Such training in art appreciation seemed to Twain as much genuine education as instruction in studied, insincere poses.

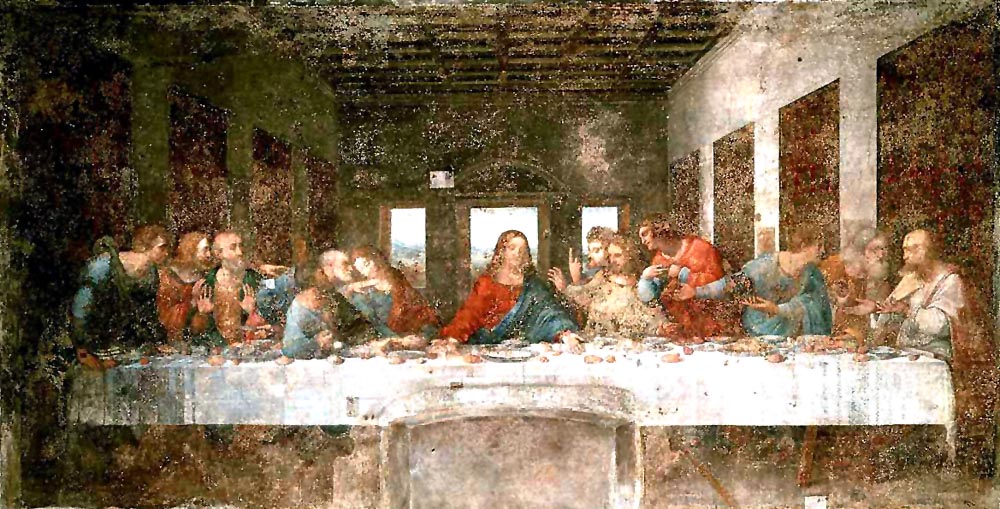

The author took his first “grand tour” in 1867—travelling through Europe and the Levant on the cruise ship Quaker City in the company of many “prosperous—and very proper—passengers.” Unlike these bourgeois travelling companions’ “conventional appreciation for all that they saw,” Twain—writing as a correspondent for the San Francisco Alta California—confessed himself underwhelmed. In particular, he described another Da Vinci, The Last Supper—“the most celebrated painting in the world”—as a “mournful wreck.” (The work was then unrestored; see it above as it looked 100 years later in the 1970s.) Twain later revised his observations for his first full-length book, 1869’s Innocents Abroad, a caricature of ugly American tourists filled with what William Dean Howells called “delicious impudence.” While the others marveled at Da Vinci’s crumbling fresco, Twain, in the current parlance, expressed a great big “meh.”

The world seems to have become settled in the belief, long ago, that it is not possible for human genius to outdo this creation of Da Vinci’s.… The colors are dimmed with age; the countenances are scaled and marred, and nearly all expression is gone from them; the hair is a dead blur upon the wall, and there is no life in the eyes.… I am satisfied that the Last Supper was a very miracle of art once. But it was three hundred years ago.

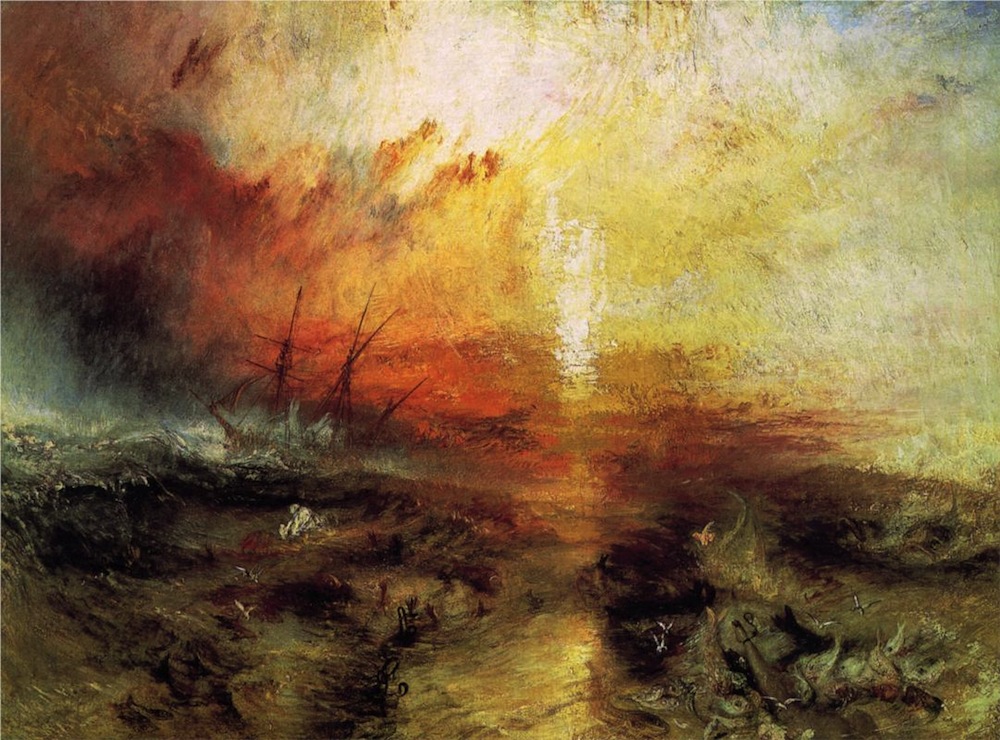

Twain and the professional critics did not always disagree. Take J.M.W. Turner’s famously riotous canvas Slave Ship (or Slavers Overthrowing the Dead and Dying: Typhoon Coming On), above. John Ruskin may have praised the work as the “noblest sea… ever painted by man” and it has come down to us as a violent representation of the horrors of the slave trade, occasioned in part, writes Stephen J. May, by Turner’s sense of “shared guilt about his own role and England’s role in condoning and perpetuating slavery’s malevolent legacy.” The anti-slavery, anti-imperialist Twain would surely have appreciated the sentiment; the painting, however, not so much. Other critics felt similarly, one calling Slave Ship a “gross outrage on nature.” Twain’s summation in an 1878 notebook is much more colorful, a piece of vintage Samuel Clemens undercutting: “Slave Ship—Cat having a fit in a platter of tomatoes.”

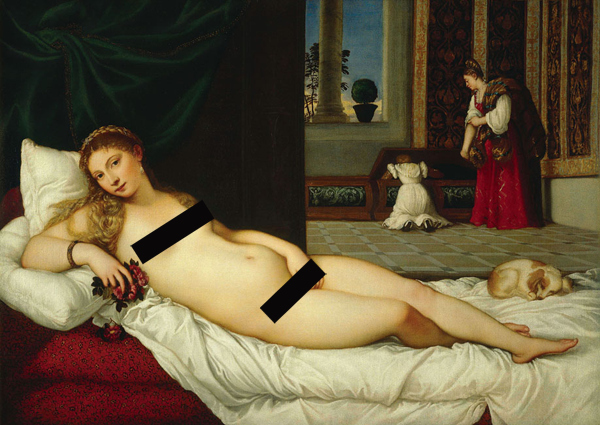

For all his snide portraits of conventional middle-class attitudes toward art, Twain could also be a bit of a prig, as we see in his response to Titian’s Venus of Urbino. In this, he was not so far removed from our own cultural attitudes (or Facebook and Google’s attitudes) about nudity. The censored version of the painting above (see the original here) comes to us via Buzzfeed, who write “Remember kids, blood and gore are fine but boobs will make you blind.” Twain seemed to have unironically agreed, railing in his 1880 travel book A Tramp Abroad against the “indecent license” afforded artists and calling Titian’s suggestive reclining nude “the foulest, the vilest, the obscenest picture the world possesses.” (Ah, if only he had lived to see the internet’s foulest depths.)

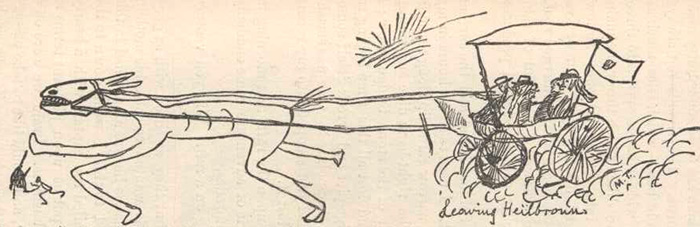

Twain’s own meager contributions to the visual arts—consisting of a dozen sketches, like that above, made for A Tramp Abroad—fall somewhat short of the standards he set for other artists. Nevertheless, he recalled in The Innocents Abroad his dismay at the “acres of very bad drawing, very bad perspective, and very incorrect proportions” in the museums and churches across Europe. What, we might wonder, could possibly move such a harsh, unsparing critic? In art, it seems, Twain valued “strict realism, grandeur of theme and scale, and propriety”—all on display in abundance in American artist Frederic Edwin Church’s The Heart of the Andes, below.

After viewing this idealized South American landscape in St. Louis, Twain called the enormous (over five feet high by ten feet wide) canvas a “most wonderfully beautiful painting.” “We took the opera glasses,” he wrote to his brother, “and examined its beauties minutely…. There is no slurring of perspective about it.” He recommended multiple viewings: “Your third visit will find your brain gasping and straining with futile efforts to take all the wonder in… and understand how such a miracle could have been conceived and executed by human brain and human hands.”

Twain, won over by this sublime spectacle, seems to have temporarily surrendered his critical faculties. In reading his response, I found myself wanting to egg him on: C’mon, what about this soft, gauzy lighting, those lumpy mountains, and the kitschy, overly-sentimental look of the whole thing? But there was room enough in Twain’s critical arsenal for genuine awe as for amused contempt at what he saw as phony expressions of the same. And that breadth of character is what made Mark Twain, well, Mark Twain.

Related Content:

Mark Twain Creates a List of His Favorite Books For Adults & Kids (1887)

Mark Twain Drafts the Ultimate Letter of Complaint (1905)

Mark Twain Writes a Rapturous Letter to Walt Whitman on the Poet’s 70th Birthday (1889)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I like so many things about Mark Twain. I have finally found something that I do not agree with him about. His taste in art is very very different from mine. I really like the Turner painting and was surprised that he was offended by the nude.

… M’am, Sir,

Very interesting, I love your article … but I repeat myself !

Thank you.

He was only rabble rousing, as was his wont.

When you write “sublime spectacle,” I’m reminded of how Clemens described a sunrise over Haleakala, on the island of Maui, in the 1860s. It’s a description that the tourism authorities still called on when I first visited there 25 years ago: “the sublimest spectacle ever witnessed.” This was a cut-down version of his actual quote: “the sublimest spectacle ever witnessed through the bottom of a tumbler.”

On this page to read about Twain’s wits, I had to triple take at your reproduction of the Venus of Urbino **CENSORED**. Open culture indeed! Il Braghettone (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniele_da_Volterra) is alive and well in the USA, it seems. Now that is one painter Twain would have loved.

I know I’m late to the party, but better late than never:

Without giving proper context to the passages where Twain criticized these paintings, the article gives off the vibe that Twain was a great hater of great art. This isn’t true in the least! If it was your intention to make Twain out to be a Southern yokel with unrefined, plebeian tastes, then according to some of the other comments posted here (by people who evidently haven’t read much of Twain beyond Huck and Tom’s adventures), you’ve certainly succeeded!

I have “A Tramp Abroad” lying before me right now. Here is the proper context to Twain’s comment about Titian’s Venus:

The chapter starts off with Twain complaining about the sudden moral censorship in media and arts. He points out that in Florence, for instance, the city has put fig-leaves on all of the marble statues, which he thought was a particularly stupid and ineffective act, since the naked statues weren’t provocative to begin with. However, he noted, very graphic nude paintings haven’t been “fig-leaved” or censored, and remain in full view of the public. He essentially called people out for being selectively moral — naked statues are bad, but nude paintings are okay.

As an example of a particularly provocative painting, he mentioned Titian’s Venus and pointed out that if he was to explicitly describe the act she was committing (namely, pleasuring herself), he’d raise a howl around the world for being grossly indecent. But if he had been a painter like Titian and drew the act, people would hail him a genius.

Did the person who wrote this article even read his sources? Or was he or she trying to slag off on Mark Twain? How sad must one’s life be, to either be too stupid to understand Mark Twain or too much of a scumbag to quote him properly.

As for his comments on Turner and other “Old Masters”, it was all tongue-in-cheek, and Mark Twain’s own comments about his photographs and drawings are obviously jokes, like Kurt Vonnegut’s sketches. You can’t take them seriously. Mark Twain was a SATIRIST, a HUMORIST, a COMEDIC WRITER. Does anybody know what humor means anymore, or only two-bit pseudo-journalistic reviews like this article are all that’s left in the world?

I think that if Titian or Da Vinci had been alive to meet Twain, they would have found his comments absolutely hilarious!

If somebody’s respect for Mark Twain diminishes this article, or this article fuels their existing jealousy of such giants like Twain, all’s worse for them and better for the rest of us normal readers. No true admirer of Twain loses respect for him, and nobody cares about those pathetic weak-minded noodles who think they are above classical American writers and try to besmirch their good reputation, but merely end up looking like obnoxious, pseudo-intellectual trash.

Surely the censored painting is a joke; or this site caters to Jehovah’s Witnesses.