Like many of us, Russian literary great Fyodor Dostoevsky liked to doodle when he was distracted. He left his handiwork in several manuscripts—finely shaded drawings of expressive faces and elaborate architectural features. But Dostoevsky’s doodles were more than just a way to occupy his mind and hands; they were an integral part of his literary method. His novelistic imagination, with all of its grand excesses, was profoundly visual, and architectural.

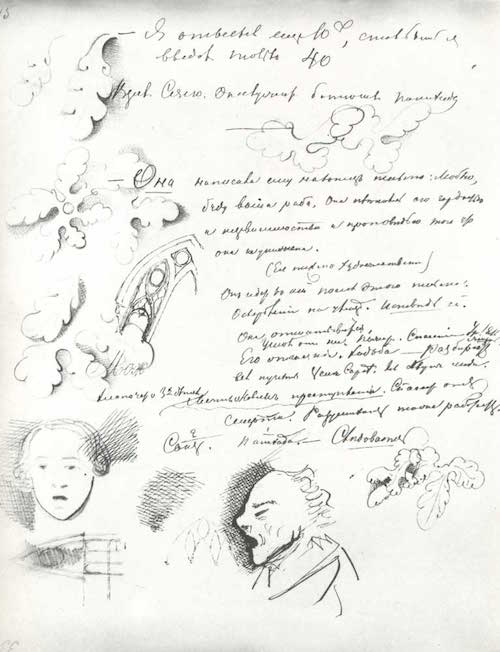

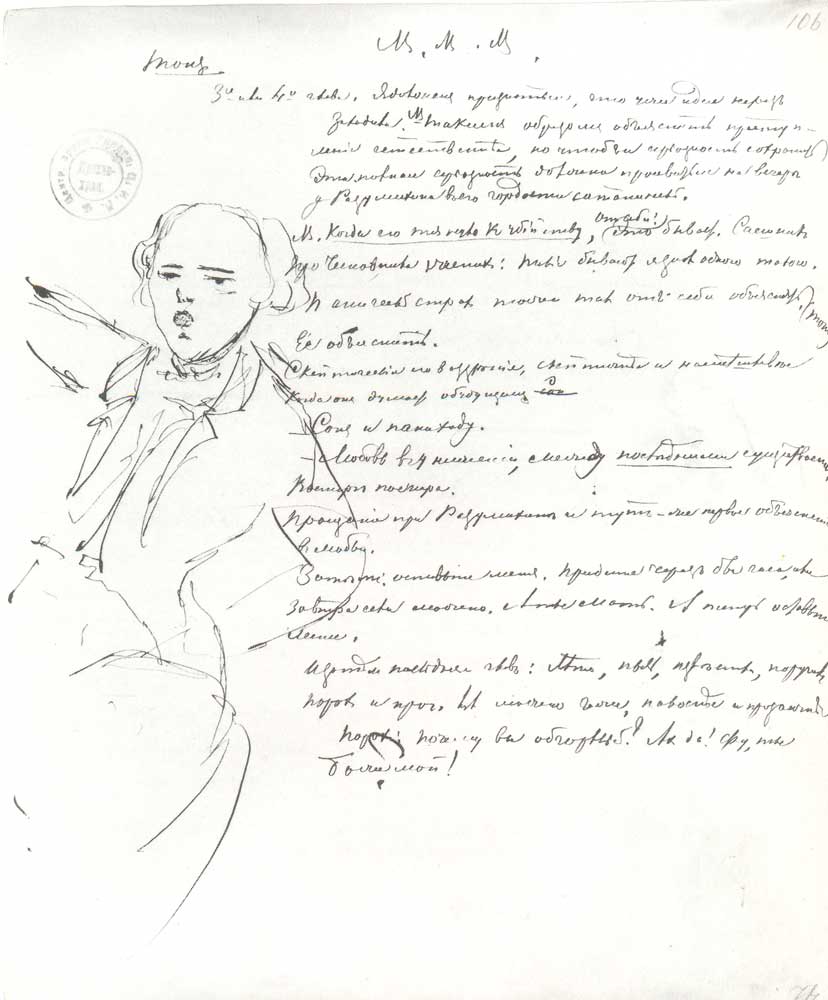

“Indeed,” writes Dostoevsky scholar Konstantin Barsht, “Dostoevsky was not content to ‘write’ and ‘take notes’ in the process of creative thinking.” Instead, in his work “the meaning and significance of words interact reciprocally with other meanings expressed through visual images.” Barsht calls it “a method of work specific to the writer.” We’ve shared a few of those manuscript pages before, including one with a doodle of Shakespeare.

Now we bring you a few more pages of doodles from the author of Crime and Punishment, a novel that, perhaps more so than any of his others, offers such vivid descriptions of its characters that I can still clearly remember the pictures I had of them in my mind the first time I read it in high school.

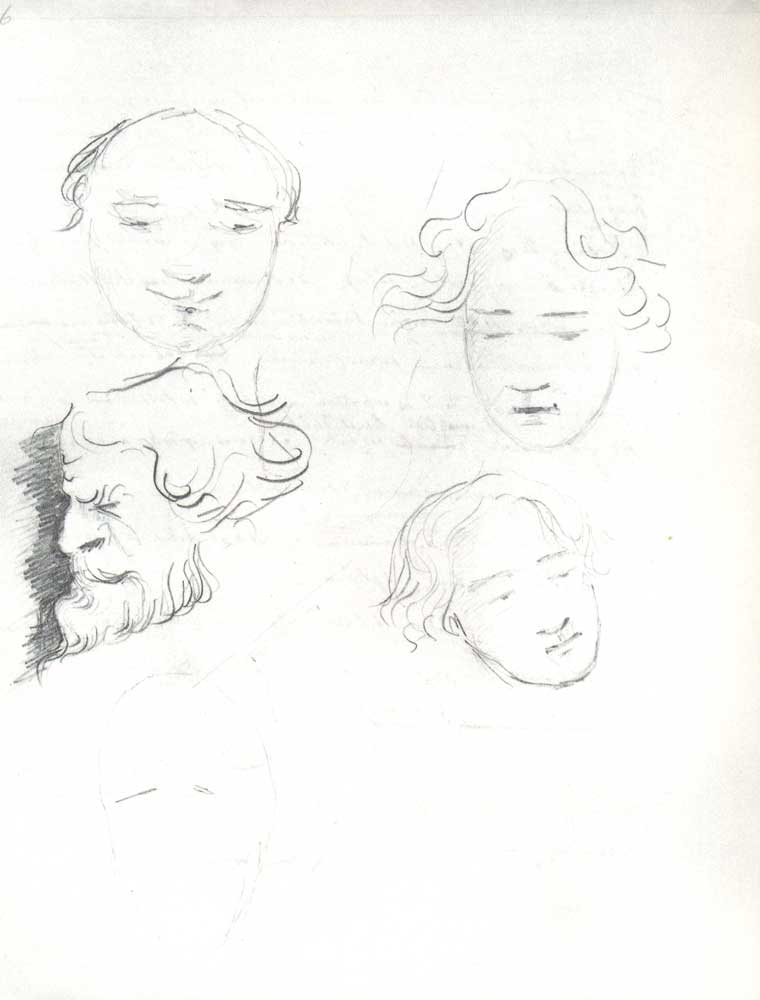

My visualizations of the angry, desperate student Raskolnikov and the sleazy sociopathic Svidrigailov do not exactly resemble the faces doodled at the the top of the post, but that is how their author saw them, at least in this early, manuscript stage of the novel.

The other faces here may be those of Sonya, police investigator Porfiry Petrovich, recidivist alcoholic father Semyon Marmelodov, and other characters in the novel, though it’s not clear exactly who’s who.

Dostoevsky had much in common with his novel’s protagonist when he began the novel in 1865. Reduced to near-destitution after gambling away his fortune, the writer was also in desperate straits. The story, writes literary critic Joseph Franks, was “originally conceived as a long short story or novella to be written in the first person,” like the feverish novella Notes From the Underground. In Dostoevsky’s manuscript notebooks, “extensive fragments of this original work are to be found here intact.”

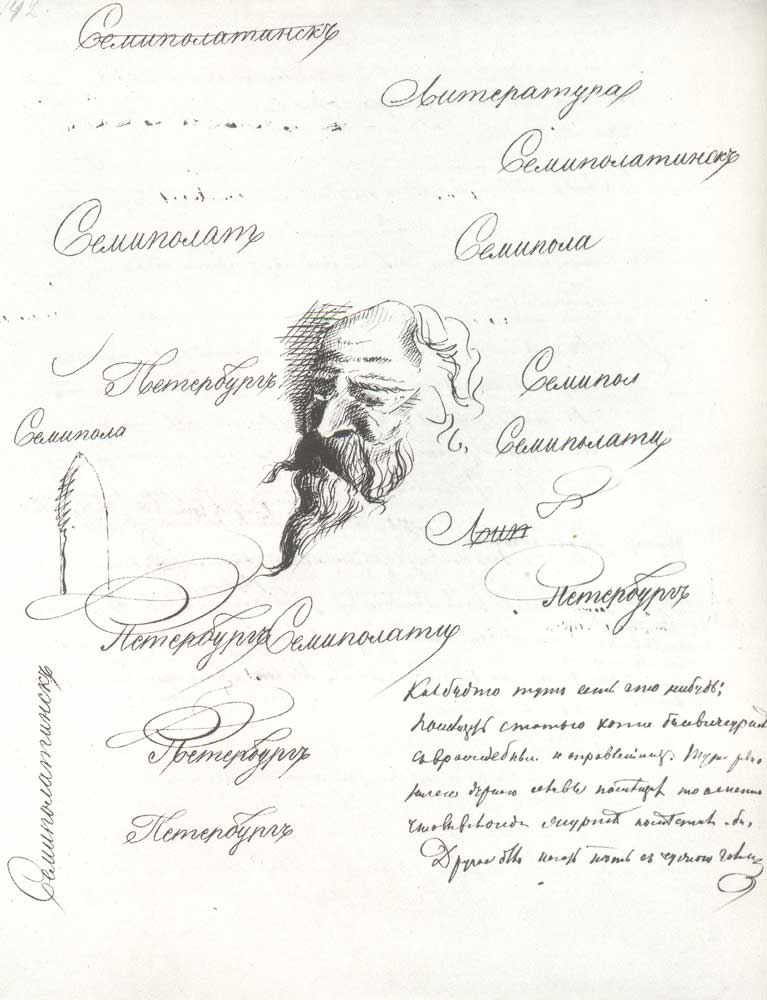

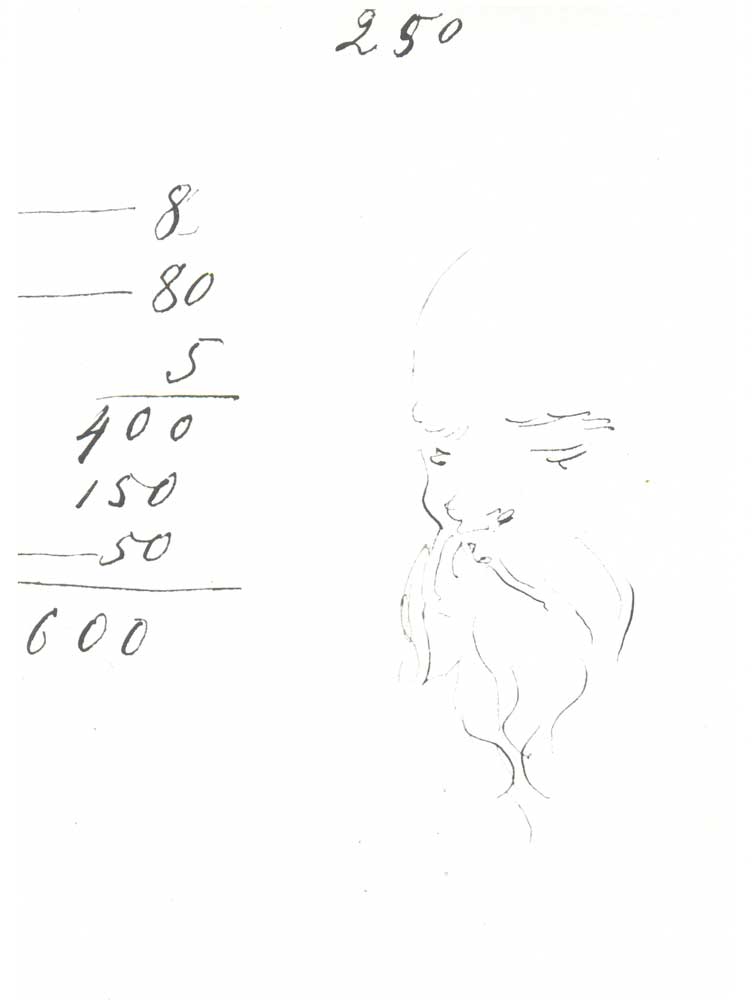

Franks quotes scholar Edward Wasiolek, who published a translation of the notebooks in 1967: “They contain drawings, jottings about practical matters, doodling of various sorts, calculations about pressing expenses, sketches, and random remarks.” In short, “Dostoevsky simply flipped his notebooks open any time he wished to write,” or to practice his calligraphy, as he does on many pages.

The pages of the Crime and Punishment notebooks resemble all of the manuscript pages of his novels in their ornamental haphazardness. You can see many more examples from novels like The Idiot, The Possessed, and A Raw Youth at the Russian site Culture, including the sketchy self portrait below, next to a few sums that indicate the author’s perpetual preoccupation with his troubled economic affairs.

Related Content:

Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

Dostoevsky Draws a Picture of Shakespeare: A New Discovery in an Old Manuscript

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Genial mi escritor favorito . Sin saberlo hago lo mismo que el , solo que mis escritos son nada. Y tenía también talento para dibujar. Un ruso que adoro y admiro intensamente.

My! Thank you for this post!!

This is amazing! Dostoevsky is my favourite writer. I just wrote an article about short stories that includes two of his own. If anyone is interested in reading, here’s a link:

https://medium.com/@SaveTheMurlocs/top-10-amazing-short-stories-that-will-make-you-think-42b996b4bf69

Dostoevsky is still and always my favorite, Crime and Punishment the best novel– and I love that he doodled his characters on notebook pages!