Recently, a Metafilter user asked the question: which books do you reread again and again, and why— whether for “comfort, difficulty, humour, identification, whatever”? It got me thinking about a few of the ways I’ve discovered such books.

Writing an essay or book about a novel is one good way to find out how well it holds up under multiple readings. You stare at plot holes, implausible character development, inconsistent chronologies, and other literary flaws (or maybe features) for weeks, months, sometimes even years. And you also live with the language that first seduced you, the characters who drew you in, the images, places, atmospheres you can’t forget….

But reading alone can mean that blind spots never get addressed. We hold to our biases, positive and negative, despite ourselves. Another great way to test the durability of work of fiction is to teach it for years, or otherwise read it in a group of engaged people, who will see what you don’t, can’t, or won’t, and help better your appreciation (or deepen your dislike).

Having spent many years doing both of these things as a student and teacher, there are a few books that survived semester after semester, and still sit prominently on my shelves, where at any time I can pull them down, open them up, and be immediately absorbed. Then there are books I read when younger, and which seemed so mysterious, so possessed of an almost religious significance, I returned to them again and again—looking for the most enchanted sentences.

If I had to narrow down to a short list the books I consistently reread, those books would come out of all three experiences above, and they would include, in no necessary order—

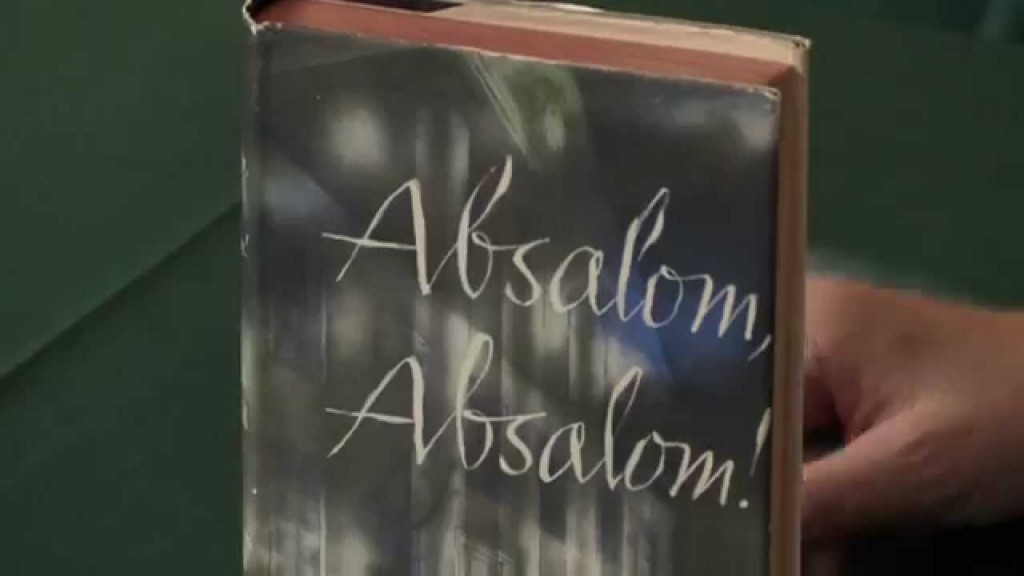

Absalom, Absalom!, by William Faulkner: I’ve written several essays on this novel, over the course of several years, and I love it as much or more as when I first picked it up. It’s a book that becomes both more grim and more darkly humorous as time goes on; its vertiginous narrative strategy creates an inexhaustible number of ways to see the story.

Wuthering Heights, by Emily Bronte: I read this novel as a child and understood almost nothing about it but the ghostly setting of “wiley, windy moors” (as Kate Bush described it) and the furious emotional intensity of Heathcliff and Catherine. These elements kept me coming back to discover just how much Bronte—like Faulkner—encircles her reader in a cyclone of possibility; multiple stories, told from multiple characters, times, and places, swirl around, never settling on what we most want in real life but never get there either—simple answers.

Song of Solomon, by Toni Morrison: Morrison’s novel extracts from the 20th century African American experience a tale of profound individual struggle, as characters in her fictional family fight to define themselves against social inequities and to transcend oppressive identities. Their failures to do so are just as poignant as their successes, and characters like Pilate and Milkman achieve an almost archetypal significance through the course of the novel. Morrison creates modern myth.

The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, by Michael Chabon. I taught this novel for years because it seemed like, and was, a great way to introduce students to the complications of plot, the joys of speculative fiction, and the empathetic imagining of other people and cultures that the novel can enable. I can think of many ways some critics might find Chabon’s book politically “problematic,” but my consistent enjoyment of its wild-eyed story has never diminished since I first picked up the book and read it straight through in a couple of days, fully convinced by its fictional world.

Labyrinths, by Jorge Luis Borges. The Argentinian writer’s best-known collection of stories and essays requires patient rereading. My first encounter with the book early in college provoked amazement, but little comprehension. I still can’t say that I understand Borges, but every time I reread him, I seem to discover some new alcove, and sometimes a whole other room, filled with inscrutable, mysterious treasures.

This list is not in any way comprehensive, but it covers a few of the books that have stayed with me, each of them for well over a decade, and a few of the reasons why. What books do you reread, and why? What is it about them that keeps you returning, and how did you discover these books? While I stuck with fiction above, I could also make a list of philosophical books, as well as poetry. Feel free to include such books in the comments section below as well.

Related Content:

The 10 Greatest Books Ever, According to 125 Top Authors (Download Them for Free)

Vladimir Nabokov Names the Greatest (and Most Overrated) Novels of the 20th Century

Read 700 Free eBooks Made Available by the University of California Press

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The single novel I’ve returned to most often is Kipling’s Kim. The richness of his tapestry, the love he feels for his characters, the urgency of the plot, and Kipling’s keen awareness of the complexity and moral ambiguity of British colonialism allow new meaning to emerge for me each time I return. The other novels that I’ve returned to more than twice include Moby Dick, The Once and Future King (although the appeal of that had begun to get musty last time I tried it), all twelve volumes of Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time, and, for easy pleasure, almost anything by Terry Pratchett.

Einstein’s Dreams by Alan Lightman

I return to books that have more than one way of access, that can be contemplated as an object, a tessellated polyhedron of multiple meanings. What come to mind are certain thick novels which contain a whole universe in them:

Lanark, by Alasdair Gray

Against the day, by Thomas Pynchon

Middlemarch, by George Eliot

Tristram Shandy, by Lawrence Sterne

La vie mode d’emploi, by Georges Perec

Rayuela, by Julio Cortázar

Earthly Powers, by Anthony Burgess

Rebecca, by Daphne du Maurier. Her gift for description and mood is a joy to read.

The Haunting of Hill House, by Shirley Jackson. A masterpiece.

Anno Dracula, by Kim Newman. Alternate history/Historical fiction of the highest order.

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee. She makes writing seem so effortless, it takes my breath away.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s, by Truman Capote. A gem of place and time, it is a lesson in the craft of writing.

Oh man, _Absalom, Absalom!_ is peerless. Also love the Chabon and the Borges. My other candidates would be:

_Light in August_, by Faulkner

_Little, Big_, by John Crowley

_Deathless_, by Catherynne M. Valente

I’m sure there are others (including many of Philip K. Dick’s novels), but these are the first to jump to mind.

If you liked Borges, you will probably enjoy Cortazar, the other great Latin American shaman. ‘Rayuela’ (Hopscotch) is an amazing experience and also the novel (or counter-novel, as it was reffered by Cortázar himself) born to be reread, among other things, because of his structure, which splits into two different sequences of chapters.

The american author and journalist C. D. B. Bryan stated in 1966: “Hopscotch is the most significant novel I have read, and one to which I return from time to time. No other novel by a living author [little shiver here] has influenced me as much, nor has interested and enchanted me more than Hopscotch. No other novel has explored so fully and completely man’s compulsion to explain human life, to seek its meaning, to challenge its mysteries. No other novel of late has devoted so much love and attention to the whole range of the writer’s art”.

Walker Percy: Love in the Ruins. The subtitle captures it: The Adventures of a Bad Catholic at a Time Near the End of the World. A little science fiction, a little romance, and a lot of philosophic world view and perspective on the human condition. Seems more relevant each time I read it. Maybe that says something about the trajectory of world events.

The Unbearable Lightness Of Being by Milan Kundera

A Hundred Years Of Solitude by Garcia Marquez

The Catcher in Rye

The Sun Also Rises

Sandman by Neil Gaiman

Gunter Grass~ Dog Years

Lawrence Durrell~ The Alexandria Quartet (Yes, it’s cheating, I know)

Peter Matthiessen~ Shadow Country

Robert Graves~ I, Claudius

Walker Percy~ Lost In The Cosmos

All 20 of Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey/Maturin series.

All 11 of C.P. Snow’s Strangers and Brothers series.

Short works for my short attention span:

1. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (Joyce)

2. The Old Man & the Sea (Hemingway)

3. Death in Venice (Mann)

4. Ficciones (Borges)

5. The Metamorphosis (Kafka)

Brothers Karamazov by Dostoyevsky

So many characters, so many motives and complicated psychological portraits. And reading it is just like a going through a soap opera :)

I agree with all of your 5 selections (especially Absalom, Absalom), but I must add a non fiction piece–Walden by HD Thoreau. I would omit Bronte if I had to remove 1 in order to add Walden. Mostly simply the most thoughtful and wryly comic book ever writ! I re-read it once per year.

Little, Big was one of my favorite discoveries in reading during 2015.

The works of Shakespeare, Moby Dick, and Walden.

Ford Madox Ford, “The Good Soldier”

Thomas hardy, “Jude the Obscure”

Melville ~ Moby Dick

Whitman ~ Leaves of Grass

Dostoyevsky ~ Crime and Punishment

Flaubert ~ Sentimental Education

Nabokov ~ Lolita, Ada

Maxwell ~ So Long, See You Tomorrow

McCarthy ~ Blood Meridian

Louise Erdrich’s The Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando.

Durrell — The Alexandria Quartet

Kazantzakis — The Last Temptation Of Christ

Duncan — I, Lucifer

Benoit — The Supreme Doctrine

It is a joy to return to a truly great read. I will likely read them all again before I depart.

Peter Temple’s books — every one of the nine. My favourite author of all times.

Michael Crichton’s “Timeline”.

Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey and Maturin series.

Rose Tremain’s “Music and Silence”.

Dickens’ “Little Dorrit” and “Our Mutual Friend”.

Hilary Mantel’s “Wolf Hall”.

Even Dick Francis’ “Banker” !

There now: a selection to offset all that amazingly high-falutin’ reading already mentioned.

[grin]