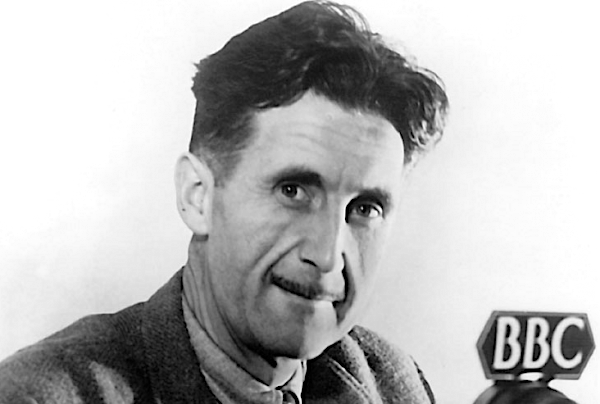

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Most everyone who knows the work of George Orwell knows his 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language” (published here), in which he rails against careless, confusing, and unclear prose. “Our civilization is decadent,” he argues, “and our language… must inevitably share in the general collapse.” The examples Orwell quotes are all guilty in various ways of “staleness of imagery” and “lack of precision.”

Ultimately, Orwell claims, bad writing results from corrupt thinking, and often attempts to make palatable corrupt acts: “Political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible.” His examples of colonialism, forced deportations, and bombing campaigns find ready analogues in our own time. Pay attention to how the next article, interview, or book you read uses language “favorable to political conformity” to soften terrible things.

Orwell’s analysis identifies several culprits that obscure meaning and lead to whole paragraphs of bombastic, empty prose:

Dying metaphors: essentially clichés, which “have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves.”

Operators or verbal false limbs: these are the wordy, awkward constructions in place of a single, simple word. Some examples he gives include “exhibit a tendency to,” “serve the purpose of,” “play a leading part in,” “have the effect of.” (One particular peeve of mine when I taught English composition was the phrase “due to the fact that” for the far simpler “because.”)

Pretentious diction: Orwell identifies a number of words he says “are used to dress up a simple statement and give an air of scientific impartiality to biased judgments.” He also includes in this category “jargon peculiar to Marxist writing” (“petty bourgeois,” “lackey,” “flunkey,” “hyena”).

Meaningless words: Abstractions, such as “romantic,” “plastic,” “values,” “human,” “sentimental,” etc. used “in the sense that they not only do not point to any discoverable object, but are hardly ever expected to do so by the reader.” Orwell also damns such political buzzwords as “democracy,” “socialism,” “freedom,” “patriotic,” “justice,” and “fascism,” since they each have “several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another.”

Most readers of Orwell’s essay inevitably point out that Orwell himself has committed some of the faults he finds in others, but will also, with some introspection, find those same faults in their own writing. Anyone who writes in an institutional context—be it academia, journalism, or the corporate world—acquires all sorts of bad habits that must be broken with deliberate intent. “The process” of learning bad writing habits “is reversible” Orwell promises, “if one is willing to take the necessary trouble.” How should we proceed? These are the rules Orwell suggests:

(i) Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

(ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

(iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

(iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

(v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

(vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

What constitutes “outright barbarous” wording he does not say, exactly. As the internet cliché has it: Your Mileage May Vary. You may find creative ways to break these rules without thereby being obscure or justifying mass murder.

But Orwell does preface his guidelines with some very sound advice: “Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations. Afterward one can choose—not simply accept—the phrases that will best cover the meaning.” Not only does this practice get us closer to using clear, specific, concrete language, but it results in writing that grounds our readers in the sensory world we all share to some degree, rather than the airy world of abstract thought and belief that we don’t.

These “elementary” rules do not cover “the literary use of language,” writes Orwell, “but merely language as an instrument for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought.” In the almost eighty years since his essay, the quality of English prose has likely not improved, but our ready access to writing guides of all kinds has. Those who care about clarity of thought and responsible use of rhetoric would do well to consult them often, and to read, or re-read, Orwell’s essay.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

10 Writing Tips from Legendary Writing Teacher William Zinsser

Stephen King’s 20 Rules for Writers

V.S. Naipaul Creates a List of 7 Rules for Beginning Writers

Nietzsche’s 10 Rules for Writing with Style

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.

Leave a Reply