Some of the best, most succinct writing advice I ever received came from the great John McPhee, via one of his former students: “Writing is paying attention.” What do you see, hear, taste, etc.? Questions of style, syntax, and punctuation come later. Obsess over them before you’ve learned to pay attention, and you’ll have nothing of interest to write about. And in order to notice what you’re noticing, you’ve got to record it; so keep a notebook with you at all times to jot down overheard expressions, thrilling sights and insights, dramatic chance encounters… hoarding material, all the time.

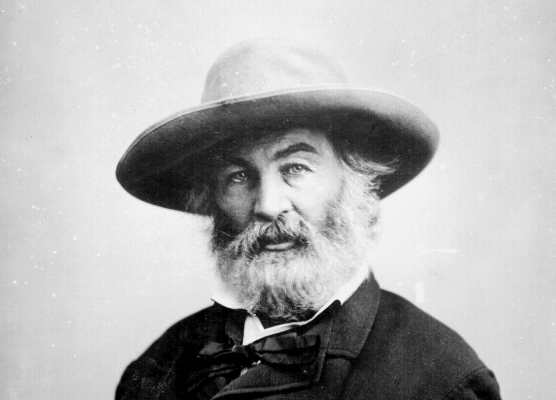

Amongst the tidal wave of advice you’ll encounter when you first begin to write—much of it contradictory and some of little practical benefit—you’d have a hard time finding anyone who disagrees with McPhee. Not even Walt Whitman, who embraced contrariness and contradiction like no other American writer, thus becoming all the more an honest reflection of the nation. Few writers spent more time noticing than Whitman, who seemingly recorded everything he saw and heard on his travels. “I heard what the talkers were talking,” he proclaimed, “I perceive after all so many uttering tongues.” Whitman—as a project called HarvardX Neuroscience dubs him—was a “poet of perception.”

But he was also a hard-headed realist with a bent toward the utilitarian and a scrappy resourcefulness that made him an artistic survivor. Whitman contained multitudes, not only in his poetry but in his writing advice. When editors of The Signal, newspaper of The College of New Jersey, asked the poet in 1888 to advise young scholars on the “literary life,” he obliged, giving the paper a brief interview in which the “gray-haired, handsome, aged poet of Camden” proffered the following (condensed in list form below):

1. Whack away at everything pertaining to literary life—mechanical part as well as the rest. Learn to set type, learn to work at the ‘case’, learn to be a practical printer, and whatever you do learn condensation.

2. To young literateurs I want to give three bits of advice: First, don’t write poetry; second ditto; third ditto. You may be surprised to hear me say so, but there is no particular need of poetic expression. We are utilitarian, and the current cannot be stopped.

3. It is a good plan for every young man or woman having literary aspirations to carry a pencil and a piece of paper and constantly jot down striking events in daily life. They thus acquire a vast fund of information. One of the best things you know is habit. Again, the best of reading is not so much in the information it conveys as the thoughts it suggests. Remember this above all. There is no royal road to learning.

Whitman’s advice contains sound, practical tips on what we might today call “professionalization.” Should we take his admonishment against writing poetry seriously? Why not? For a good portion of his life, Whitman earned a living “whacking away,” as he liked to say often, at more utilitarian forms of writing, from reportage to an advice column. Whitman took seriously his role as a voice of working people and perhaps saw this interview as an occasion to address them.

Whitman’s “seething rejection of poetry,” writes Nicole Kukawski in the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, should not surprise us; it is “simply part of his attack on conventionality in all respects… poetry can never be ‘utilitarian’—in no way can it reach the masses for their benefit.” Unlike our day, poetry was ubiquitous in late nineteenth century America, part of an entrenched, highly conventional polite discourse. Who knows, maybe a Whitman of the early 21st century would feel very differently on this point. Surely we could use a great deal more “poetic expression” these days.

Whitman’s final piece of advice accords fully with John McPhee’s—and several hundred other writers and teachers. But in Whitman’s estimation, noticing, and acquiring “a vast fund of information,” was not only essential to the literary life but also key to pursuing an “individualistic,” real-world self-education. “One subject about which Whitman did not contradict himself,” writes Kukawski, “was his consistent belief that the scholar should learn by encountering life instead of reading books alone.” There may be no better exemplar of that philosophy in American letters than Walt Whitman himself.

via Austin Kleon

Related Content:

Walt Whitman’s Poem “A Noiseless Patient Spider” Brought to Life in Three Animations

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Always write from within, let it flow, never force it!The Lords Blessing

Because you came to me before the end

Now it is for your soul that I will send

You have realized your sin’s and that is good

You are sorry for sinning against your brotherhood

In the end you were no longer fighting Life

You finally gave in to its strife

You finally realized that I wanted you to love me by faith not fear

That is why you couldn’t see me but knew that I was here

At first you hated life and its demands

Until you reached out for my loving hands

Tell your family, “Please do not grieve!”

For I promised eternity for he that would believe

Tell them you will be waiting in the Promised Land

Someday together you will play in the sand

Tell them to go after that one that went astray

Bring them closer, don’t push them away

Work together, stay by their side

Teach them my love, but don’t insult their pride

Show them my love, raise their spirits high

Tell your family I needed you here in heaven up high

Tell them please do not shed a tear

Before long they will join you here

Tell them that I have forgiven you for all of your sin

Tell them I also opened heavens gate to let you in

Be a good friend and a good host

Show them the way to the Holy Ghost

Be there when they fall to lift them high

Do all these things and they join you in the sky

By: Wayne Hoss

I really like this concept. It is true that in writing you can tell when the writer means it or doesn’t mean it. Imagery that is made up does not feel genuine, and it becomes easy to lose your reader. If you take the time to observe, you can create the kind of imagery that will capture a reader. Thank you for all of your helpful tips for aspiring writers!