On Friday, a person who has insulted, demeaned, and threatened tens of millions of the country’s citizens will take the oath of office for the presidency of the United States. That’s an extraordinary thing, and the reaction will also be extraordinary—a Women’s March the following day in Washington, DC expected to draw hundreds of thousands of every gender, race, creed, and orientation. Sister marches and protests will take place in every major city on the East and West Coast and everywhere in-between, as well as internationally in cities like London, Sydney, Buenos Aires, Calgary, Barcelona, Dar es Salaam… the list goes on and on and on.

Why Women’s Marches if these events are all-inclusive? In addition to responding to the public displays of contempt for women we’ve witnessed over and over in the past year, the events intend to reaffirm the rights of all people. The organizers succinctly state that “women’s rights are human rights. We stand together, recognizing that defending the most marginalized among us is defending all of us.”

A Rawlsian progressive notion, and also a “Kingian” one, a description the march applies to its nonviolent principles. What they don’t say is that there is also significant historical precedent for the action. Over 100 years ago, another women’s march coincided with a presidential swearing-in, this time of Woodrow Wilson in March of 1913.

Marching for the cause of suffrage, women from around the country and the world arrived in DC on March 3rd, the day before Wilson’s inauguration. Many of those marchers had hiked 234 miles from New York in 17 days, bearing a letter to the President-elect, writes Mashable, “demanding that he make suffrage a priority of his administration and warning that the women of the nation would be watching ‘with an intense interest such as has never before been focused upon the administration of any of your predecessors.’” Organized by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the march promised, in their words, “the most conspicuous and important demonstration that has ever been attempted by suffragists in this country.”

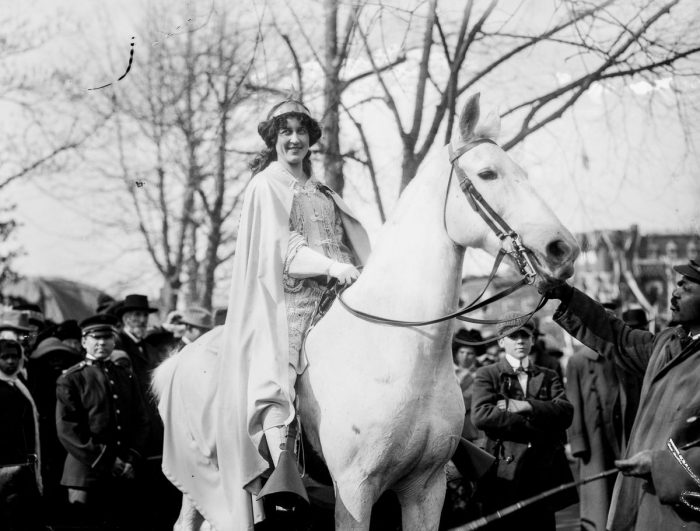

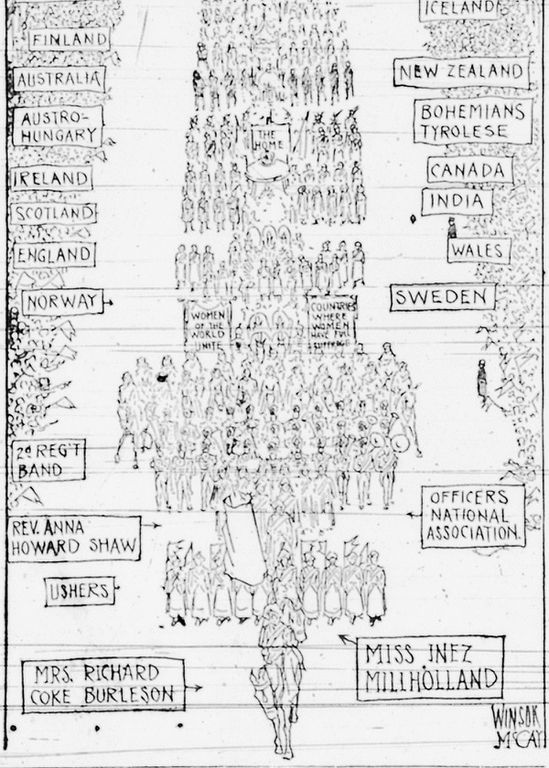

The parade was filled with pageantry. “Clad in a white cape astride a white horse,” writes the Library of Congress, “lawyer Inez Milholland led the great woman suffrage parade down Pennsylvania Avenue in the nation’s capital. Behind her stretched a long line with nine bands, four mounted brigades, three heralds, about twenty-four floats, and more than 5,000 marchers.”

As you can see in the images here from the LoC—including the drawing of the parade route above by Little Nemo cartoonist Winsor McKay—the parade drew a huge global coalition. It also drew ridicule, harassment, and violence from groups in DC for the following day’s festivities. As the LoC writes:

[A]ll went well for the first few blocks. Soon, however, the crowds, mostly men in town for the following day’s inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, surged into the street making it almost impossible for the marchers to pass. Occasionally only a single file could move forward. Women were jeered, tripped, grabbed, shoved, and many heard “indecent epithets” and “barnyard conversation.” Instead of protecting the parade, the police “seemed to enjoy all the ribald jokes and laughter and in part participated in them.” One policeman explained that they should stay at home where they belonged.

Many marchers were injured; “two ambulances ‘came and went constantly for six hours, always impeded and at times actually opposed, so that doctor and driver literally had to fight their way to give succor.’” The event included several prominent figures, including Helen Keller, “who was unnerved by the experience.” Also present was Jeannette Rankin, who, writes Mashable, “would become the first woman elected to the House of Representatives four years later.” Nelly Bly marched, as did journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, “who marched with the Illinois delegation despite the complaints of some segregationist marchers.”

In fact, though the selective images suggest otherwise, the march was more inclusive than the suffragist movement is generally given credit for. Over the objections of mostly Southern delegates, many black women joined the ranks. After “telegrams and protests poured in” protesting segregation, members of the National Association of Colored Women “marched according to their State and occupation without let or hindrance,” noted the NAACP journal Crisis. And yet, when the women’s vote was finally achieved in 1920, that general category still did not include black women. The misogyny on display that day was vicious, but still perhaps not as endemic as the country’s racism, which existed in large degree within suffragist groups as well.

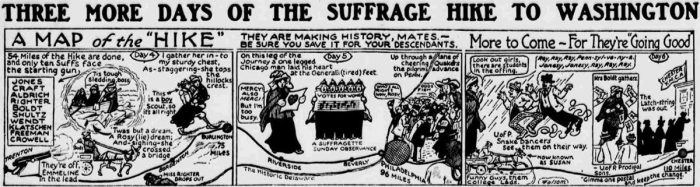

Once the press broadcast news of the marchers’ mistreatment, there was a massive public outcry that helped reinvigorate the suffrage movement. Several other artists than McKay found inspiration in the march; Cleveland Plain Dealer cartoonist James Donahey, for example, “substituted women for men in a cartoon based on the famous painting ‘Washington Crossing the Delaware,’” writes the Library of Congress. Another cartoonist, George Folsom, documented the stages of the hike from New York, with captions addressed to male readers. The strip above says, “they are making history mates—be sure you save it for your descendants.” Another strip reads “Brave women all, none braver mates. Put this away and look at it when they win.”

At the Library of Congress’s American Women site, you’ll find a wealth of resources for researching the history and impact of the 1913 Suffrage Parade. To find out more about the hundreds of contemporary Women’s Marches—open to people of every “race, ethnicity, religion, immigration status, sexual identity, gender expression, economic status, age or disability”—see the website here or read this Rolling Stone interview with organizer Linda Sarsour.

Related Content:

Odd Vintage Postcards Document the Propaganda Against Women’s Rights 100 Years Ago

Download Images From Rad American Women A‑Z: A New Picture Book on the History of Feminism

The First Feminist Film, Germaine Dulac’s The Smiling Madame Beudet (1922)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

..Well said, and well represented Mr. Jones..!!

But these protesters didn’t have a problem with Warren G Harding? Go figure.

In 1913, in the USA, you also couldn’t vote if you were a man who was: native American, Chinese immigrant, resident of DC, poor, black or latino, not a land-owner, younger than 21, or deployed overseas. And of course the vast majority-male prison population can have its voting rights taken away even today.

But many of these men could certainly be drafted into war by their “elected” government, and that did happen repeatedly in the early- and mid-20th century.

Perspective.

All excellent points, Randy. For most of the nation’s history, the vote was more far exclusive than most people know.

Thanks, Rho!

Back in the days when American women had REAL, and not First-World problems, as women here today have.

The fact that the comments section on this wonderful article consists only of men talking amongst themselves about other issues is further evidence that action is still needed.

Amy

???

Amy, women are the ones who do not give men the space to speak. Every time men talk about THEIR historical exclusion from the social and political world, THEIR lack of representation in government, THEIR unequal pay for equal work, all I hear is women dismissing these very real problems by suddenly bringing up the discrimination their minority populations have faced (while conveniently forgetting that people of either gender could belong to those groups and thus that gender is not the factor that is causing the discrimination!). Can you imagine believing that any injustice one group experiences erases the legitimacy and importance of the injustices another group faces? It’s completely unreasonable, and if we didn’t live in this infernal matriarchy no one would give any credence to such arguments!

This article was pretty kewwwl bruh.10/10 would reccomend. used it to convince my grandma of stuff.