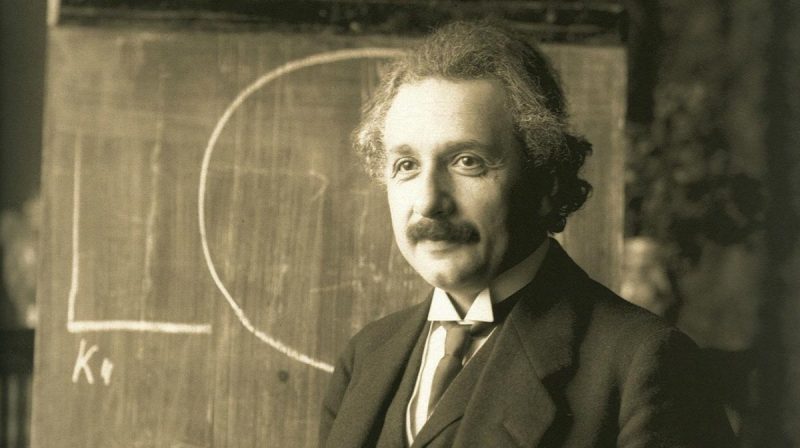

Image by Ferdinand Schmutzer, via Wikimedia Commons

The concept of one-world government has long been a staple of violent apocalyptic prophecy and conspiracy theories involving various popes, the UN, FEMA, the Illuminati, and lizard people. In the real world, one-world government has been a goal of the global Comintern and many of the corporate oligarchs who triumphed over the Soviets in the Cold War. For good reason, perhaps—with the exception of sci-fi utopias like Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek—we generally tend to think of global government as a threatening idea. But that has not always been the case, or least it wasn’t for Albert Einstein who proposed global governance after the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Einstein’s role in the development of those weapons may have been minimal, according to the physicist himself (the truth is a little more complicated). But he later expressed regret, or at least a total rethinking of the issue, in his many interviews, letters, and speeches. In 1952, for example, Einstein wrote a short essay called “On My Participation in the Atom Bomb Project” in which he recommended that all nations “abolish war by common action” and referred to the pacifist example of Gandhi, “the greatest political genius of our time.”

Five years earlier, we find Einstein in a less than hopeful mood. In a 1947 open letter to the General Assembly of the United Nations, he laments that “since the victory over the Axis powers… no appreciable progress has been made either toward the prevention of war or toward agreement in specific fields such as control of atomic energy and economic cooperation.” The solution as he saw it required a “modification of the traditional concept of national sovereignty.” It’s a clause that might have launched a thousand militia manifestoes. Einstein elaborates:

For as long as atomic energy and armaments are considered a vital part of national security no nation will give more than lip service to international treaties. Security is indivisible. It can be reached only when necessary guarantees of law and enforcement obtain everywhere, so that military security is no longer the problem of any single state. There is no compromise possible between preparation for war, on the one hand, and preparation of a world society based on law and order on the other.

So far this sounds not simply like a one-world government but like a one-world police state. But Einstein’s proposal gets a much more comprehensive treatment in an earlier Atlantic Monthly editorial published in 1945. Here, he admits that many of his ideas are “abstractions” and lays out a scheme to ostensibly protect against global totalitarianism.

Membership in a supranational security system should not, in my opinion, be based on any arbitrary democratic standards. The one requirement from all should be that the representatives to supranational organization—assembly and council—must be elected by the people in each member country through a secret ballot. These representatives must represent the people rather than any government—which would enhance the pacific nature of the organization.

The greatest obstacle to a global government was not, Einstein thought, U.S. mistrust, but Russian unwillingness. After making every effort to induce the Soviets to join, he writes in his UN letter, other nations should band together to form a “partial world Government… comprising at least two-thirds of the major industrial and economic areas of the world.” This body “should make it clear from the beginning that its doors remain wide open to any non-member.”

Einstein corresponded with many people on the issue of one-world government, recommending in one letter that a “permanent world court” be established to “constrain the executive branch of world government from overstepping its mandate which, in the beginning, should be limited to the prevention of war and war-provoking developments.” He does not foresee the problem of an executive who seizes power through nefarious means and ignores institutional checks on power and privilege. As for the not-insignificant matter of the economy, he writes that “the freedom of each country to develop economic, political and cultural institutions of its own choice must be guaranteed at the outset.”

Ideological conflicts over economics seemed to him “quite irrational,” as he wrote in his Atlantic editorial. “Whether the economic life of America should be dominated by relatively few individuals, as it is, or these individuals should be controlled by the state, may be important, but it is not important enough to justify all the feelings that are stirred up over it.” Like any honest intellectual, Einstein reserved the right to change his mind. By 1949 he had come to see socialism as a necessary antidote to the “grave evils of capitalism”—the gravest of which, he wrote, is “an oligarchy of private capital the enormous power of which cannot be effectively checked even by a democratically organized political society”—even one, presumably, with global legislative reach.

Related Content:

Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

This article is very misleading.

Anyone who has read Einstein’s books will know that he was dead against one world government. He makes this very clear in his own words.

it is well known that einstein advocated one world government after wwII. i saw a lecture on television in the 70s where he advocated this.

here is audio from one of these lectures

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lmQYtzhe0w