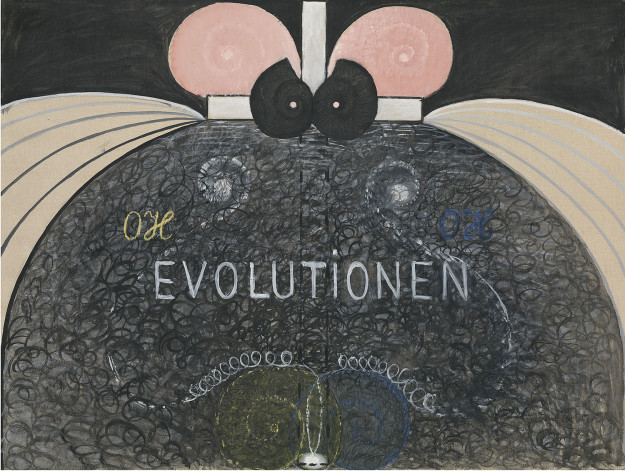

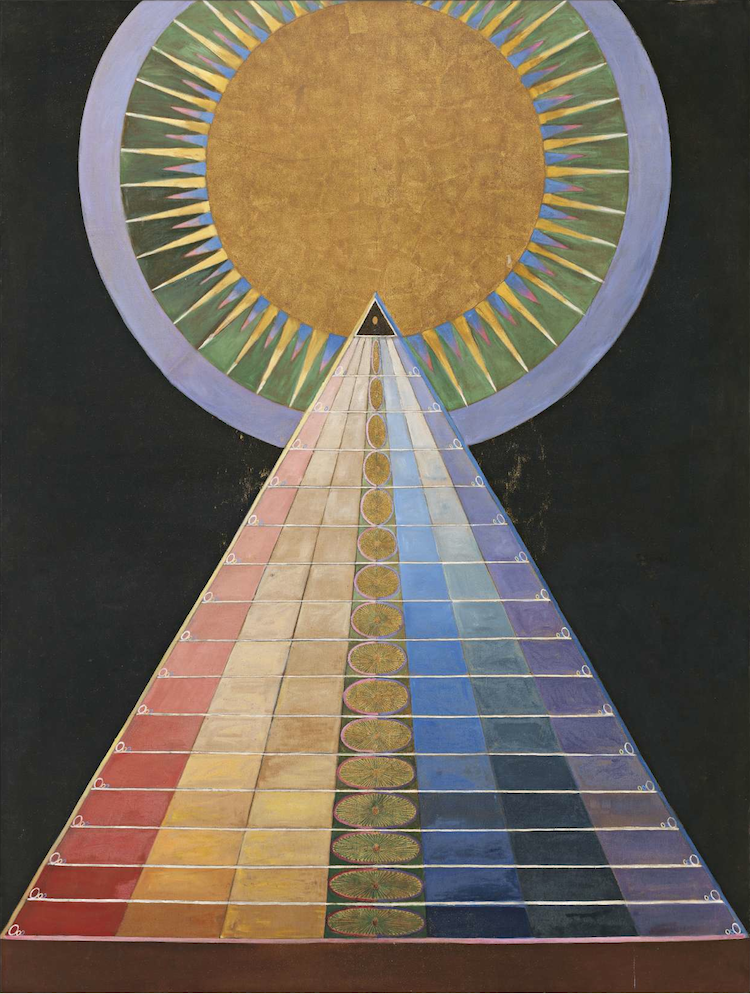

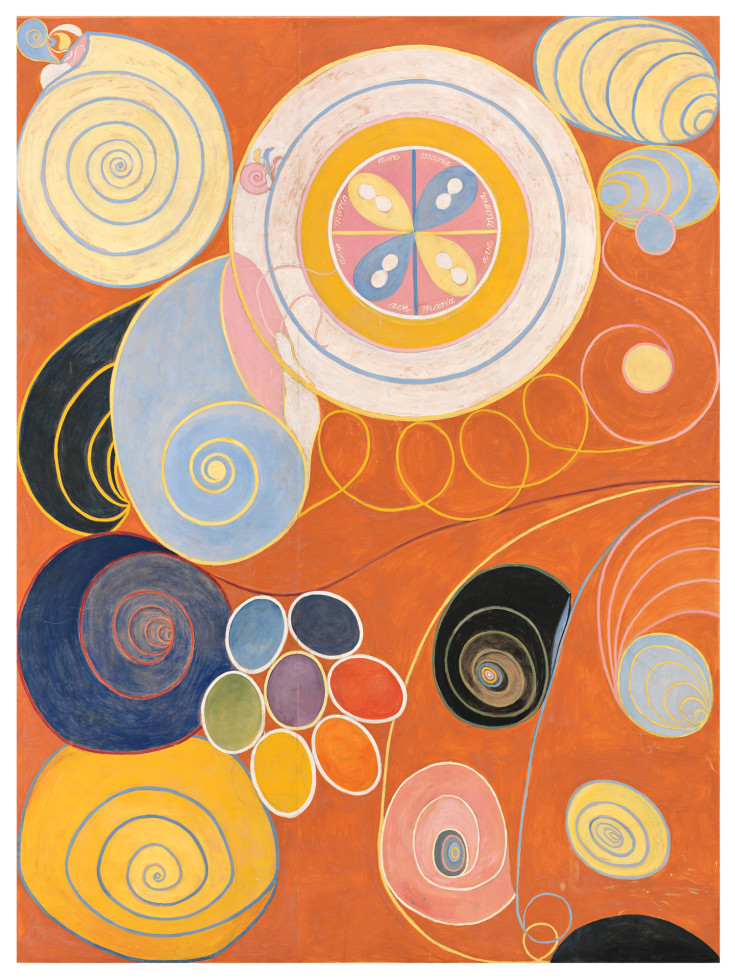

In a post last year, Colin Marshall wrote of the Swedish abstract painter Hilma af Klint, who “developed abstract imagery,” notes Sweden’s Moderna Museet, “several years before” contemporaries like Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich. Much like Kandinsky, who articulated his theories in the treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art, af Klint “assumed that there was a spiritual dimension to life and aimed at visualizing context beyond what the eye can see.” Influenced by spiritualism and theosophy, she “sought to understand and communicate the various dimensions of human existence.”

Born in 1862 and raised in the Swedish countryside, af Klint began her studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm after her family relocated to the city. “After graduating and until 1908,” Moderna Museet writes, “she had a studio at Kungsträdgården in central Stockholm.

She painted and exhibited portraits and landscapes in a naturalist style.” But as a result of her experiences in séances in the late 1870s, af Klint became interested in “invisible phenomena.”

In 1896, Hilma af Klint and four other women formed the group “De Fem” [The Five]. They made contact with “high masters” from another dimension, and made meticulous notes on their séances. This led to a definite change in Hilma af Klint’s art. She began practising automatic writing, which involves writing without consciously guiding the movement of the pen on the paper. She developed a form of automatic drawing, predating the surrealists by decades. Gradually, she eschewed her naturalist imagery, in an effort to free herself from her academic training. She embarked on an inward journey, into a world that is hidden from most people.

During one such séance, in 1904, af Klint reported that she had “received a ‘commission,’” Kate Kellaway writes at The Guardian, “from an entity named Amaliel who told her to paint on ‘an astral plane’ and represent the ‘immortal aspects of man.’” From 1906 to 1915, she produced 193 paintings, “an astonishing outpouring,” which she called “Paintings for the Temple.”

Hers is a strange story. Even in a time when many famous contemporaries, like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, professed similar beliefs and spiritual practices, not many claimed to be taking dictation directly from spirits in their work. The question af Klint raises for art historians is whether she was “a quirky outsider” or “Europe’s first abstract painter, central to the history of abstract art.” Her mystical eccentricities constitute a large part of the reason she has remained obscure for so long. Rather than seek fame and acclaim for her originality, af Klint stipulated when she died in 1944 at age 81 that “her work—1,200 paintings, 100 texts and 26,000 pages of notes—should not be shown until 20 years after her death.”

Still, it took a further 22 years before her work was seen in public, at a 1986 Los Angeles show called “The Spiritual in Art.” While her peers developed large followings in their lifetimes and took part in influential movements, af Klint cultivated a private, insular world all her own, not unlike that of William Blake, who also remained mostly obscure during his life, though not necessarily by choice. Her choice to hide her work came out of an early encounter, Dangerous Minds notes, with Rudolf Steiner, “who was similarly following a path towards creating a synthesis between the scientific and the spiritual” and who told her “these paintings must not be seen for fifty years as no one would understand them.”

Now that af Klint’s work has been exhibited in full, most recently by the Moderna Museet, curators like Iris Müller-Westermann believe, as Kellawy notes, “that art-historical wrangles should not get in the way of work that needs to be seen.” Although af Klint may not have played an integral historical role in the development of abstract painting, her expansive body of work will likely inspire artists, scholars, and esoteric seekers for centuries to come.

Learn more about af Klint’s work at Moderna Museet, the Hilma af Klint Foundation website, The Art Story and Dangerous Minds.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

https://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2013/03/busapagliatheosophy-and-peggy-lee.html any connection to Besant’s “Thought Forms” ?