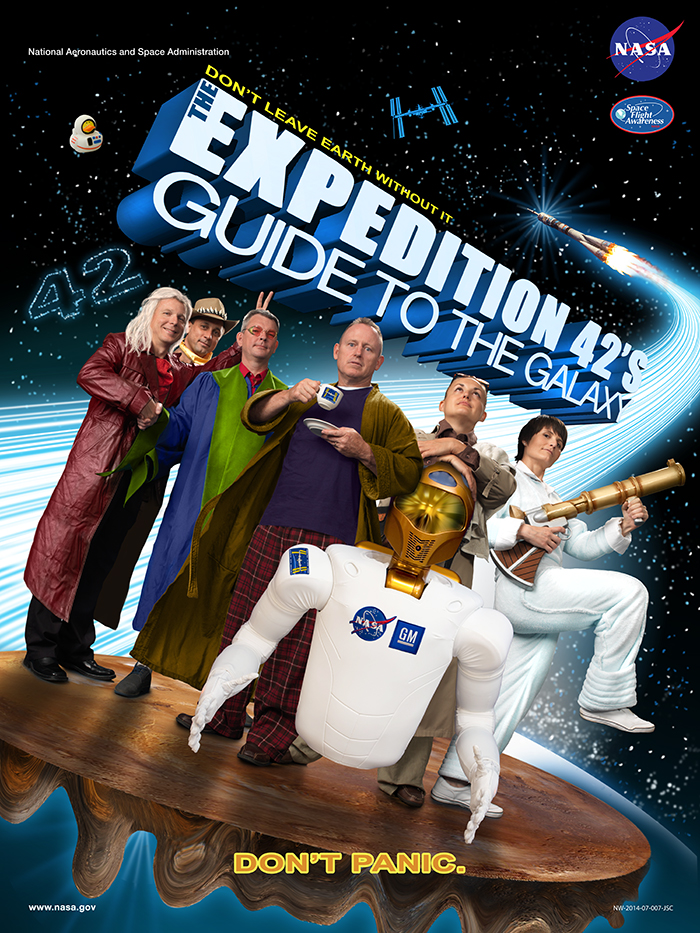

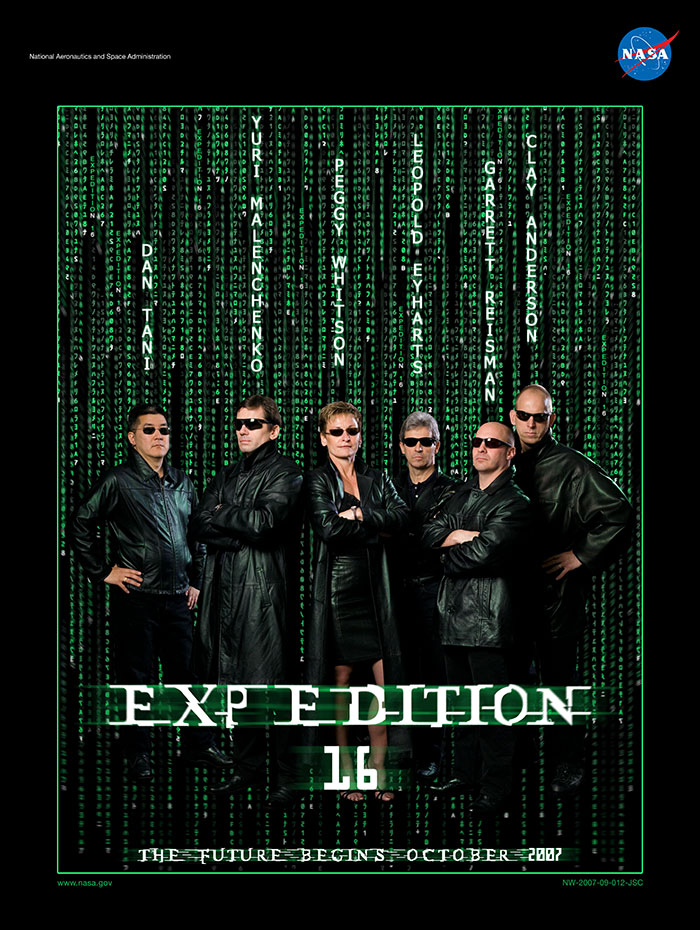

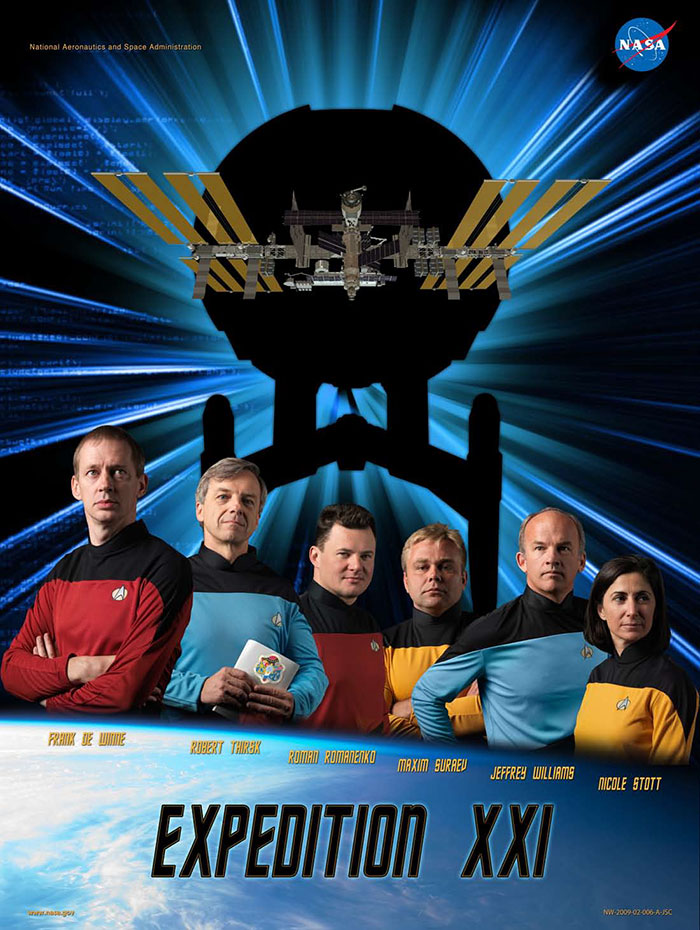

For just over eighteen years now, NASA has been conducting expeditions to the International Space Station. Each of these missions has not just a name, or at least a number (last week saw the launch of Expedition 58), but an official poster with a group photo of the crew. “These posters were used to advertise expeditions and were also hung in NASA facilities and other government organizations,” says Bored Panda. “However, when astronauts got bored of the standard group photos they decided to spice things up a bit.”

And “what’s a better way to do that other than throwing in some pop culture references?” As anyone who has ever worked with scientists knows, a fair few of them have somehow made themselves into living compendia of knowledge of not just their field but their favorite books, movies, and television shows — not always, but very often, books, movies, and television shows science-fictional in nature.

The prime example, it hardly bears mentioning, would be Star Trek, but the well of fandom at NASA runs much deeper than that.

You’ll get a sense of how far that well goes if you have a look through the Expedition poster archive at NASA’s web site. There you’ll find not just pop culture references but elaborately designed tributes — downloadable in high resolution — to the likes of not just Star Trek but Star Wars, The Matrix, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (the sole possible theme, Douglas Adams fans will agree, for Expedition 42), and even Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, which first gave dystopian sci-fi its visual form in 1927 (and which you can watch here). Albums are also fair game, as evidenced by the Abbey Road poster for Expedition 26.

Bored Panda calls these posters “hilariously awkward,” but opinions do vary: “I love them,” writes Boing Boing’s Rusty Blazenhoff. “I think they’re fun and creative.” And whatever you think of the concepts, can you fail to be impressed by the sheer attention to detail that has clearly gone into replicating the source images? It’s all more or less in line with the formidable graphic design skill at NASA, previously featured here on Open Culture, that has gone into its posters celebrating space travel and the 40th anniversary of the Voyager missions.

Going through the Expedition poster archive, I notice that none seems yet to have paid tribute to Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, surely one of the most powerful pieces of outer space-related cinema ever made. Granted, that film has much less to do with teamwork and camaraderie than the intense psychological isolation of the individual, which would make it tricky indeed to recreate any of its memorable images as proud group photos. But if NASA’s poster designers can’t take on that mission, nobody can.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

NASA Lets You Download Free Posters Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the Voyager Missions

How the Iconic 1968 “Earthrise” Photo Was Made: An Engrossing Visualization by NASA

NASA Presents “The Earth as Art” in a Free eBook and Free iPad App

Wonderfully Kitschy Propaganda Posters Champion the Chinese Space Program (1962–2003)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.