It’s an enduring irony of art history: artists whose work has come to define high culture are often characterized by various mental health issues. But the artwork of ordinary, anonymous people who struggle with those same issues is regarded as therapy, maybe, or a diversion, or a meaningless form of busy work. Though the art world has created a market for “outsider art,” it can seem like such work and its creators get viewed through an ethnographic lens rather than humanizing portraits of the artist.

As Michel Foucault demonstrated in Madness and Civilization, institutions sprung over the course of modern European history to quarantine certain classes of people from the rest of society, even if it is troublingly clear to many of us that the distinctions cannot hold—hence, perhaps, the morbid fascination with the madness of famous professional artists. In 1922, German psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn challenged this reigning orthodoxy with the publication of Artistry of the Mentally Ill.

The book, writes the Public Domain Review, “reflected a breakdown of high culture’s claim to ‘civilization,’ exposing the misery and turmoil at the heart of modern life.… Against the grain, the book granted voice to the previously marginalised: those incarcerated, those deemed insane, those suffering under poverty, those untrained, those in the wrong type of institution.”

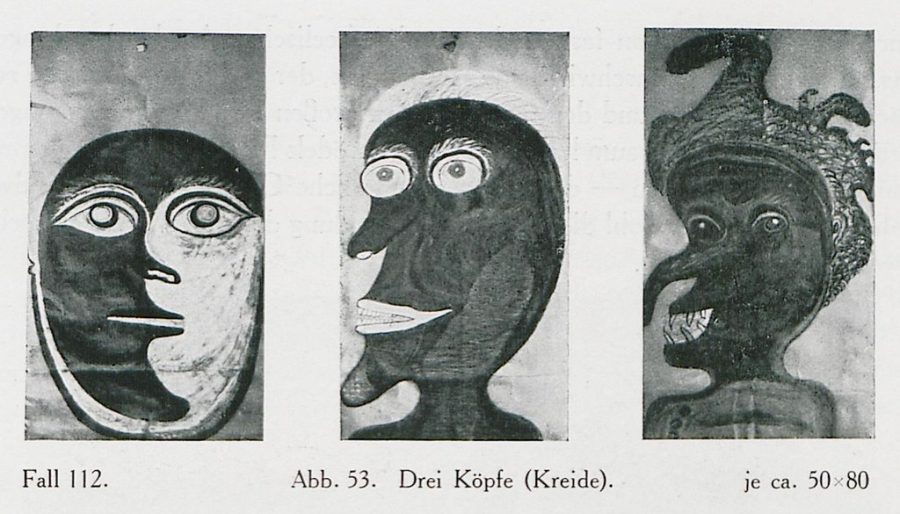

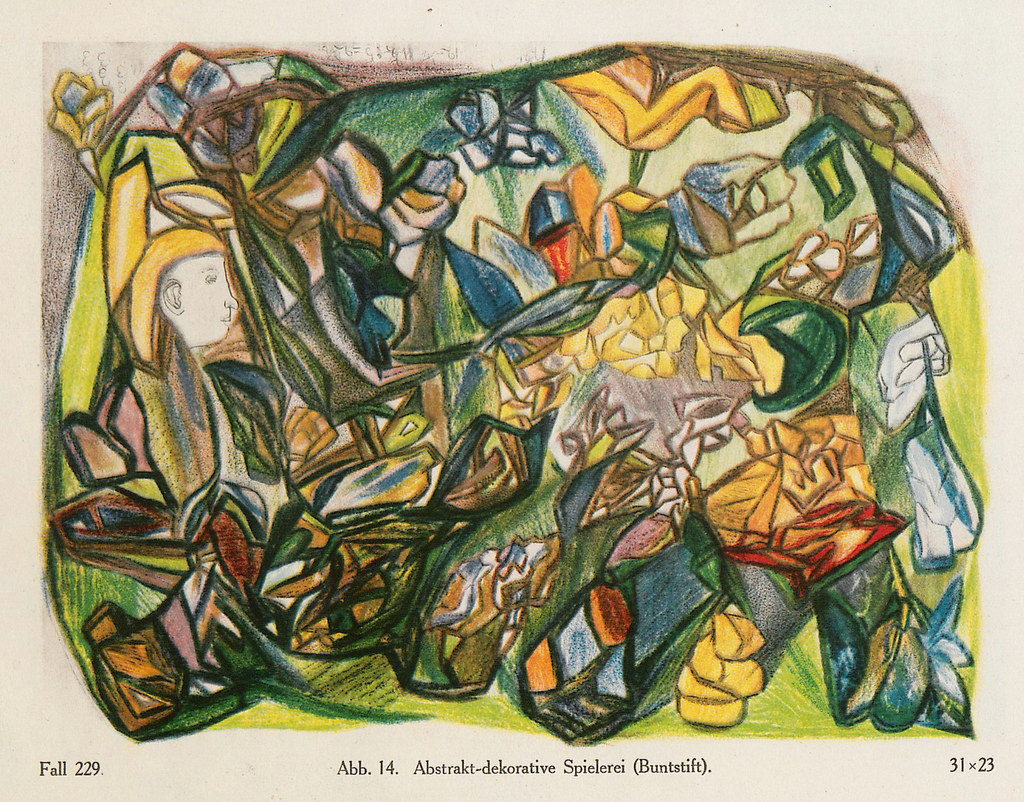

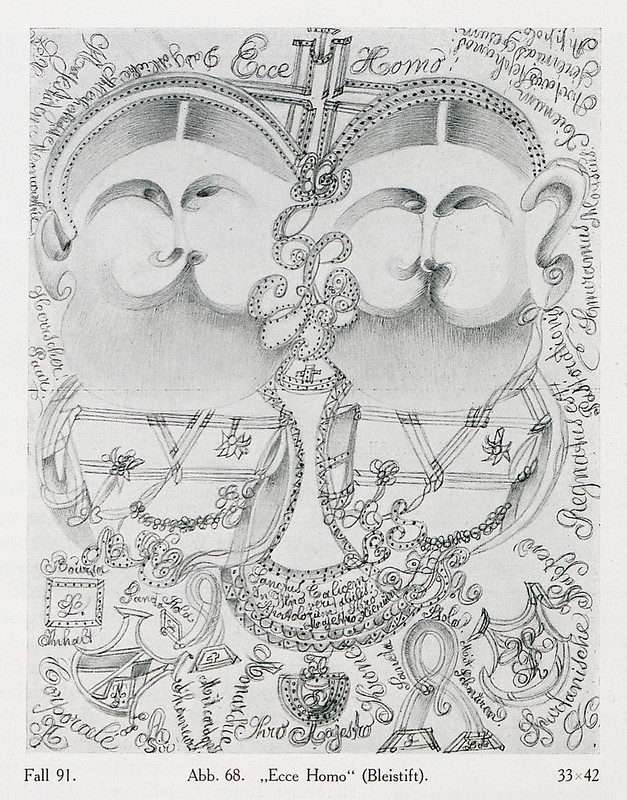

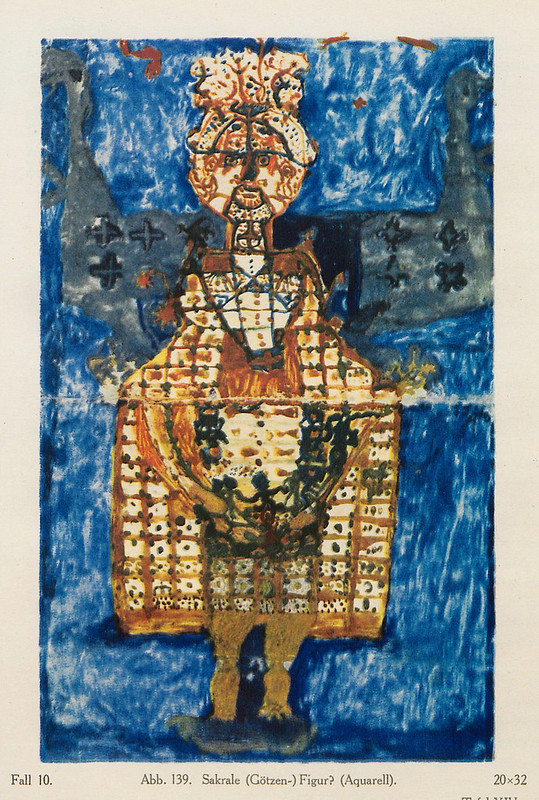

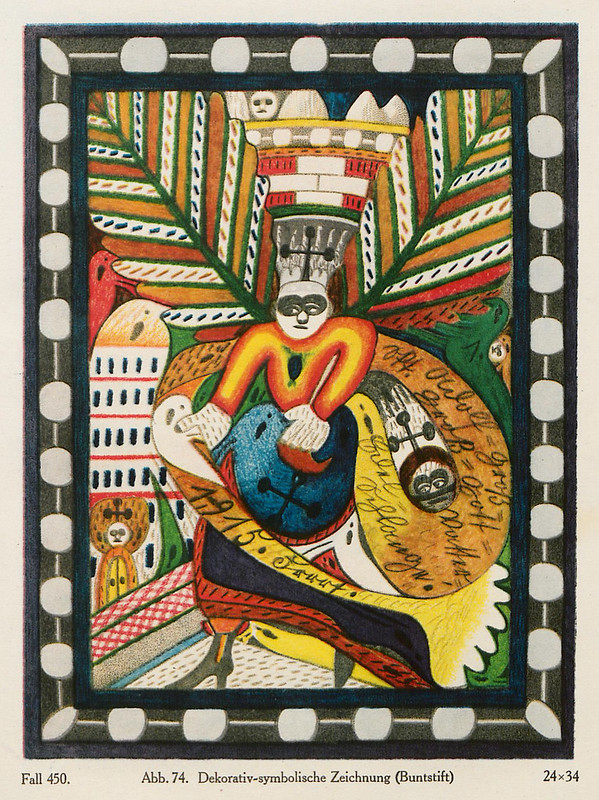

It granted those artists an audience, more to the point, of appreciative fellow artists like Paul Klee, Max Ernst, and Jean Debuffet (who would coin the term Art Brut in response). As should be abundantly clear from the small sampling of images here from the book, modernists took much from the images they saw in Prinzhorn’s book, most of it the unattributed and anonymous work of schizophrenic artists, some of whom themselves draw from earlier modernist trends.

When the Nazis held their “Degenerate Art” exhibitions in 1937, a portion of Prinzhorn’s collection of “over 5000 paintings, drawings, and carvings” was included next to the avant-garde artists it influenced. Art historian Stephanie Barron argues that “one quarter of the illustration pages in the [Degenerate Art Exhibiton’s] guide featured reproductions of the work of these psychiatric patients.” Modernists identified, in complicated ways, with those excluded from civilization, and they were subjected to the same treatment—“the insane and the avant-garde were here equated, both equally pathologized.”

Prinzhorn’s book receded into obscurity, along with the artists it carefully collected and published. It deserves to be far better known, both for its own sake and for its significant influence on the early 20th century avant-garde, and hence all subsequent avant-garde art. The book takes the work it presents seriously—not as childlike attempts or therapeutic interventions, but as expressions of six basic drives “that give rise to image making,” as the Public Domain Review summarizes.

Those universal drives include “an expressive urge, the urge to play, an ornamental urge, an ordering tendency, a tendency to imitate, and the need for symbols. For Prinzhorn, image making is driven by our intense desire to leave traces.” Art, wrote Prinzhorn, represents “an urge in man not to be absorbed passively into his environment, but to impress on it traces of his existence beyond those of purposeful activity.”

The theories of artists like Kandinsky and Debuffet expressed some similar ideas. The former ascended to the realm of spirit and symbol, and the latter acerbically castigated the empty, out-of-touch veneration of high culture. Who knows what the artists here had in mind when creating their work? In Prinzhorn’s analysis, theoretical concerns may be largely irrelevant. The creation of art, by anyone, is a universal human drive that requires no special training, no social sanction, no web of brokers, curators, and collectors. Maybe this is a threatening message to people who police the boundaries of culture.

The middle classes of his day, wrote Debuffet, were “convinced that [their] fashionable knowledge legitimizes the preservation of their caste. They work at persuading the lower classes of this, at convincing some of them of the necessity to safeguard art, that is to say armchairs, that is to say the bourgeois who know with which silk it is proper to upholster these armchairs.” Reducing art to a status symbol turns it into so much furniture, he argued; a “recourse to antique styles takes the place of good taste.” In the “raw art” of the mentally ill, Debuffet and other modernists saw a renewal of a primal human drive, the creative act.

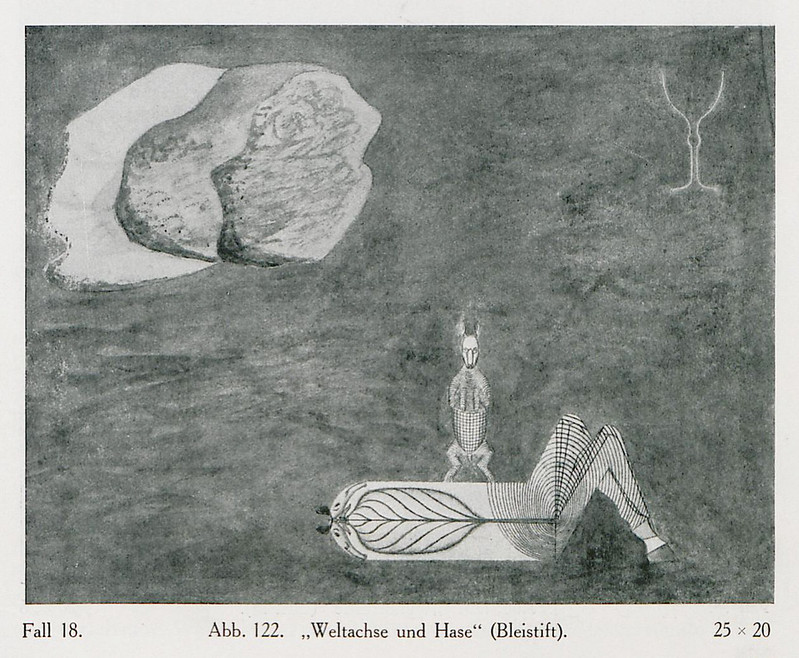

Prinzhorn’s neglected book is out of print, though you can purchase an expensive 1972 edition on Amazon, and even an expensive Kindle version. See much more of this incredible artwork at the Public Domain Review and read brief profiles from the ten schizophrenic artists Prinzhorn identified in a later section of the book. Artists like Karl Brendel, an amputee former bricklayer from Turingian, who carved haunting wood sculptures and began his art career sculpting with chewed bread, and August Neter, to whom 10,000 figures once appeared in a single vision that later became the subject of enigmatic pencil drawings like World Axis and Rabbit, below.

Related Content:

Artist Draws Nine Portraits on LSD During 1950s Research Experiment

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I find this kind of art fascinating because of the unexplored regions of the human mind that it represents. Fragmentation is a big ingredient in many of these pictures , just as it was with music in the age of German expressionism. Our eyes are better trains in our ears,.

One of the most important art books ever published.

This is pretty eye opening, as someone who has recently begun painting and drawing. I have always been reluctant to pursue art because of the ideas that people are either born with a talent for it, need to go to school for it or are driven to it by some mysterious mystical drive. And I have been hesitant because of the elitist aspect of art, and the ivory towers from which people look down on untrained and unschooled artists. No more. Its all bullshit and always was. I wonder what sort of hells those people with mental illness went through and what they experienced, in life and in their minds, in order to get those images onto paper or canvas. I wonder how much credit they were given by the artists that were “inspired” by them.