I first came to Jane Austen prepared to dislike her, reared as I had been to think of good fiction as socially transgressive, experimental, full of heavy, life-or-death moral conflicts and existentialist anti-heroes; of extremes of dread and sorrow or alienated extremes of their lack. Austen’s characters seemed too perky and perfect, too circumscribed and wholesome, too untroubled by inner despair or outer calamity to offer much in the way of interest or example.

This is an opinion shared by more perceptive readers than myself, including Charlotte Brontë, who called Pride and Prejudice “an accurate daguerreotype portrait of a commonplace face.” Brontë “disliked [Austen] exceedingly,” writes author Mary Stolz in an introduction to Emma. The author of Jane Eyre pronounced that “Miss Austen is only shrewd and observant,” where a novelist like George Sand is “sagacious and profound.”

A cursory reading of Austen can seem to confirm Brontë’s faint praise. Consider the first description of her heroine matchmaker, Emma:

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence, and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.

No great, shocking disasters befall Emma. She is buffeted neither by war nor poverty, crime, disease, oppression or any other essentially dramatic conflict. She ends the novel joining hands in marriage with charming gentleman farmer Mr. Knightly, content, maybe ever-after, in “perfect happiness.”

Rarely if ever in Austen do we find the torments, spiritual strivings, sublime and grotesque imaginings, proto-science-fiction, and world-historical consciousness of contemporaries like William Blake, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, or Mary Shelley. Austen is “famous,” writes Stolz, “for having lived through the period of the French Revolution without ever mentioning it in her writings.”

To see this as a critique, however, is to seriously misjudge her. “She did not deal in revolutions of this order. Not a traveled woman, she wrote only of what she knew”: life in English country villages, the travails of “love and money,” as she put it, the everyday longings, courtesies, and discourtesies that make up the majority of our everyday lives.

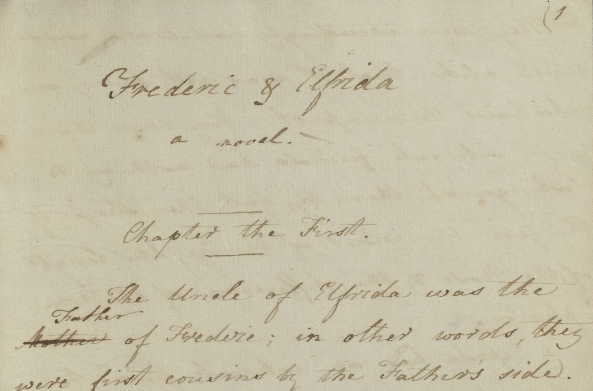

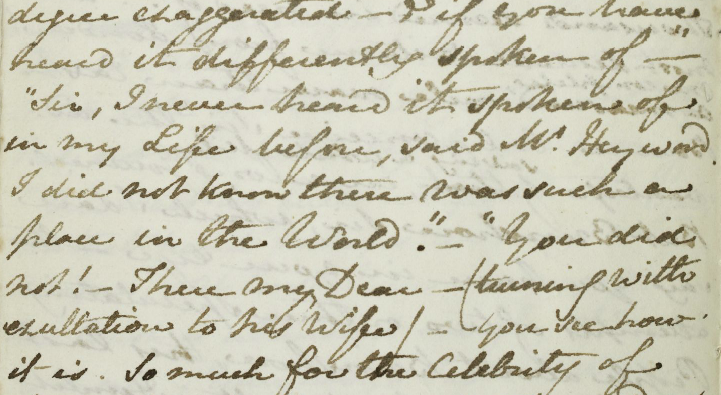

We can see Austen doing just that in her own hand at the Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts Digital Edition. A collection of scanned manuscripts from the Bodleian, British Library, Pierpont Morgan Library, private collectors, and King’s College, Cambridge, this project “represents every stage of her writing career and a variety of physical states: working drafts, fair copies, and handwritten publications for private circulation.”

This is primarily a resource for scholars; much of this work has been published in printed editions, including the Juvenilia (read some of that writing here) and unfinished drafts like The Watsons and her last, uncompleted, novel, Sanditon. (One still-in-print 1975 edition collects the three unfinished novels found at the digital collection). Each digital edition of the manuscript includes a head note on the textual history, provenance, and physical structure, as well as a transcription of the text. There is also an option to view a “diplomatic edition” that transcribes the text with all of Austen’s corrections and additions.

Yet any Austen fan will appreciate seeing her witty, incisive style change and take shape in her own neat script. In an age of superheroes, historical and fantasy epics, and dystopian fantasies, we are beset by “the big Bow-Wow strain,” as Walter Scott self-effacingly called his own novels. In Austen’s writing, we find what Scott described as an “exquisite touch which renders commonplace things and characters interesting from the truth of the description and the sentiment.” She wraps her truths in wicked irony and a satirical voice, but they are truths we recognize as wise and compassionate in her domestic dramas and our own.

Austen knew well that her settings and characters were limited. She made no apologies for it and clearly needn’t have. “Three or four families in a country village,” she wrote to her niece Anna, “is the very thing to work on.” She also knew well the universal tendencies that blind us to the variety found within the everyday, whether our everyday is a sleepy country village life or a tech-laden, 21st-century city.

She almost seems to sigh wearily in Emma when she observes, “human nature is so well disposed toward those who are in interesting situations” … so much so that we fail to notice what’s going on all around us all the time. She wrote neither for money nor fame, and her work wasn’t even published with her name until after her death in July 1817, but she has since become fiercely beloved for the very qualities Brontë disparaged.

Austen didn’t miss a thing, which makes her novels as canny and insightful (and big-screen and fan-fiction adaptable) as when they were first written over two-hundred years ago. Enter the Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts Digital Edition here.

Related Content:

An Animated Introduction to Jane Austen

Download the Major Works of Jane Austen as Free eBooks & Audio Books

Jane Austen Used Pins to Edit Her Manuscripts: Before the Word Processor & White-Out

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply