Victorian culture can seem grim and even ghoulish to us youth-obsessed, death-denying 21st century moderns. The tradition of death photography, for example, both fascinates and repels us, especially portraiture of deceased children. But the practice “became increasingly popular,” notes the BBC, as “Victorian nurseries were plagued by measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, rubella—all of which could be,” and too often were, “fatal.”

Adults did not fare much better when it came to the epidemic spread of killer diseases. Surrounded inescapably by death, Victorians coped by investing their world with totemic symbols, cultural artifacts known as memento mori, meaning “remember, you must die.” Tuberculosis, cholera, influenza… at any moment, one might take ill and waste away, and there would likely be little medical science could do about it.

Perhaps the best approach, then, was an acceptance of death while in the bloom of health, in order to not waste the moment and to learn to pay attention to what mattered while one could. Memento mori drawings, paintings, jewelry, photographs, and trinkets have populated European cultural history for centuries; death as an ever-present companion, not to be hidden away and feared but solemnly, respectfully given its due.

Or maybe not so respectfully, as the case may be. Some of these novelties, like the skeleton alarm clock at the top, look more like they belong at the bottom of a fish tank than a proper parlor mantle. “Presumably when the alarm went off,” writes Allison Meier at Hyperallergic, “the skeleton would shake its bones.” Wake up, life is short, you could die at any time. “Part of the collections of Science Museum, London, it’s believed to be of English origin and date between 1840 and 1900.”

The Tim Burton-esque tchotchke appeared in a 2014 British Library exhibit called Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination, with many other such objects of varying degrees of artistry: “200 objects from a span of 250 years, all centered on the Gothic tradition in art, literature, music, fashion, and most recently film.” Memento mori artifacts offer visceral reminders that real, daily confrontations with disease and death were “at the base of much of Gothic literature and art.”

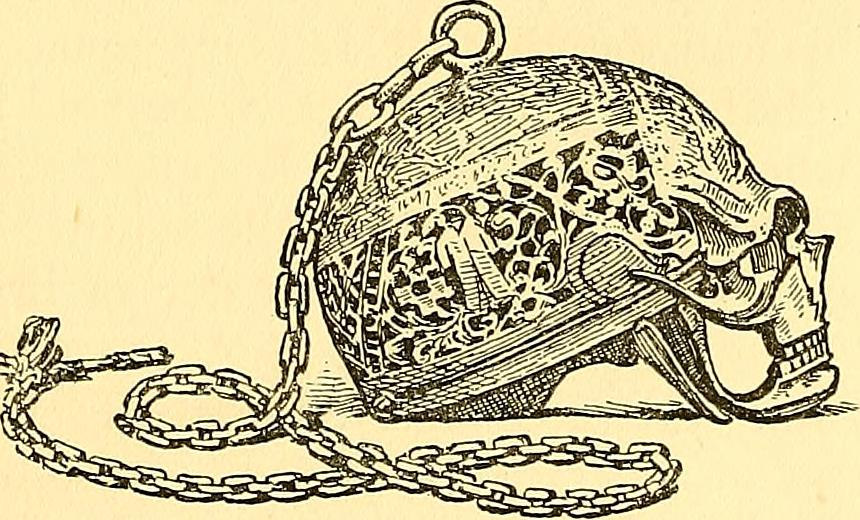

Where we now tend to read the Gothic as primarily reflective of social, cultural, and religious anxieties, the prevalence of memento mori in European homes both low and high (such as Mary Queen of Scots’ skull watch, in an 1896 illustration above) shows us just how much the gloomy strain of thinking that became the modern horror genre derives from a desire to confront mortality head on, so to speak, and finding that looking death in the face brings on ancient uncanny dread as much as healthy gallows humor and stoic, stiff-upper-lip reckoning with the ultimate fact of life.

Related Content:

An Artist Crochets a Life-Size, Anatomically-Correct Skeleton, Complete with Organs

Celebrate The Day of the Dead with The Classic Skeleton Art of José Guadalupe Posada

Old Books Bound in Human Skin Found in Harvard Libraries (and Elsewhere in Boston)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Dear Open Culture Editors, ‘open culture’ implies that images used will have #AltTxt that transfers to all platforms ❣️