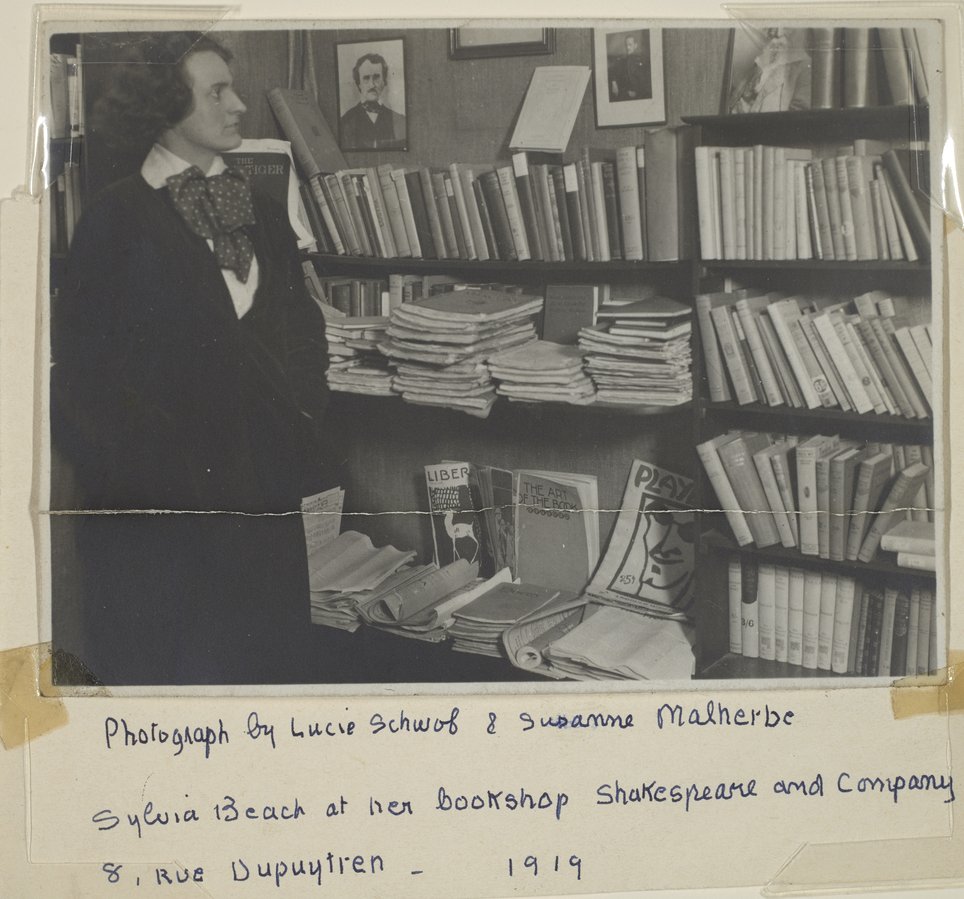

Great writers don’t come out of nowhere, even if some of them might end up there. They grow in gardens tended by other writers, readers, editors, and pioneering booksellers like Sylvia Beach, founder and proprietor of Shakespeare and Company. Beach opened the English-language shop in Paris in 1919. Three years later, she published James Joyce’s Ulysses, “a feat that would make her—and her bookshop and lending library—famous,” notes Princeton University’s Shakespeare and Company Project. (Infamous as well, given the obscenity charges against the novel in the U.S.)

Just as the publication of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl put Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights at the center of the Beat movement, so Joyce’s masterpiece made Shakespeare and Company a destination for aspiring Modernists.

The shop was already “the meeting place for a community of expatriate writers and artists now known as the Lost Generation.” Along with Joyce, there gathered Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound, and Gertrude Stein, all of whom not only bought books but borrowed them and left a handwritten record of their reading habits.

Through a large-scale digitization project of the Sylvia Beach papers at Princeton, the Shakespeare and Company Project will “recreate the world of the Lost Generation. The Project details what members of the lending library read and where they lived, and how expatriate life changed between the end of World War I and the German Occupation of France.” During the thirties, Beach began to cater more to French-speaking intellectuals. Among later logbooks we’ll find the names Aimé Césaire, Jacques Lacan, and Simone de Beauvoir. Beach closed the store for good in 1941, the story goes, rather than sell a Nazi officer a copy of Finnegans Wake.

Princeton’s “trove of materials reveals, among other things,” writes Lithub, “the reading preferences of some of the 20th century’s most famous writers,” it’s true. But not only are there many famous names; the library logs also record “less famous but no less interesting figures, too, from a respected French physicist to the woman who started the musicology program at the University of California.” Shakespeare and Company became the place to go for thousands of French and expat patrons in Paris during some of the city’s most legendarily literary years.

“English-language books are expensive,” if you’ve arrived in the city in the 1920s, the Project explains—“five to twenty times the price of French books.” English-language holdings at other libraries are limited. Readers, and soon-to-be famous writers, go to Shakespeare and Company to borrow a copy of Moby Dick or pick up the latest New Yorker.

You find Shakespeare and Company on a narrow side street, just off the Carrefour de l’Odéon. You step inside. The room is filled with books and magazines. You recognize a framed portrait of Edgar Allan Poe. You also recognize a few framed Whitman manuscripts. Sylvia Beach, the owner, introduces herself and tells you that her aunt visited Whitman in Camden, New Jersey and saved the manuscripts from the wastebasket. Yes, this is the place for you.

The lending library had different membership plans (you can learn about them here) and kept careful records with codes indicating the status of each borrower. These records are still being digitized and the Project is ongoing. It does not officially launch until next month. But at the moment, you can: “Search the lending library membership. Browse the lending library cards. Read about joining the lending library. Download a preliminary export of Project data. In June, you will be able to search and browse the lending library’s books, track the circulation of your favorite novels—and discover new ones.”

See how these literary communities shaped and reshaped themselves around what would become “the most famous bookstore in the world.”

via Lithub

Related Content:

James Joyce Picked Drunken Fights, Then Hid Behind Ernest Hemingway

7 Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

Gertrude Stein Gets a Snarky Rejection Letter from Publisher (1912)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

If I could be reincarnated in the past, I’d love to live as Sylvia Beach.

Photo of Sylvia Beach by Lucie Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe: aka Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore.