What’s the world’s oldest computer? If you answered the 5‑ton, room-sized IBM Mark I, it’s a good guess, but you’d be off by a couple thousand years or so. The first known computer may have been a handheld device, a little larger than the average tablet. It was also hand-powered and had a limited, but nonetheless remarkable, function: it followed the Metonic cycle, “the 235-month pattern that ancient astronomers used to predict eclipses,” writes Robby Berman at Big Think.

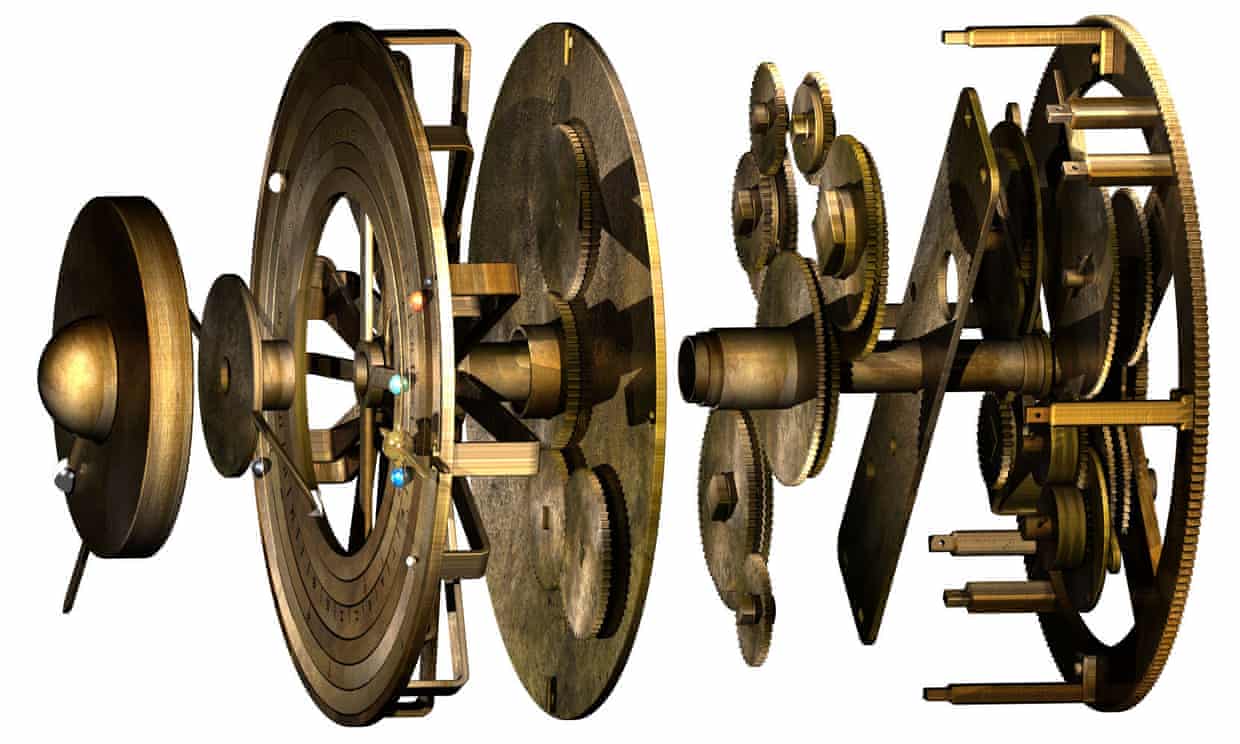

The ancient artifact known as the Antikythera mechanism — named for the Greek Island under which it was discovered — turned up in 1900. It took another three-quarters of a century before the secrets of what first appeared as a “corroded lump” revealed a device of some kind dating from 150 to 100 BC. “By 2009, modern imaging technology had identified all 30 of the Antikythera mechanism’s gears, and a virtual model of it was released,” as we noted in an earlier post.

The device could predict the positions of the planets (or at least those the Greeks knew of: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn), as well as the sun, moon, and eclipses. It placed Earth at the center of the universe. Researchers studying the Antikythera mechanism understood that much. But they couldn’t quite understand exactly how it worked, since only about a third of the complex mechanism has survived.

Image by University College London

Now, it appears that researchers from the University College of London have figured it out, debuting a new computational model in Scientific Reports. “Ours is the first model that conforms to all the physical evidence and matches the scientific inscriptions engraved on the mechanism itself,” lead author Tony Freeth tells The Engineer. In the video above, you can learn about the history of the mechanism and its rediscovery in the 20th century, and see a detailed explanation of Freeth and his team’s discoveries.

“About the size of a large dictionary,” the artifact has proven to be the “most complex piece of engineering from the ancient world” the video informs us. Having built a 3D model, the researchers next intend to build a replica of the device. If they can do so with “modern machinery,” writes Guardian science editor Ian Sample, “they aim to do the same with techniques from antiquity” — no small task considering that it’s “unclear how the ancient Greeks would have manufactured such components” without the use of a lathe, a tool they probably did not possess.

Image by University College London

The mechanism will still hold its secrets even if the UCL team’s model works. Why was it made, what was it used for? Were there other such devices? Hopefully, we won’t have to wait another several decades to learn the answers. Read the team’s Scientific Reports article here.

Related Content:

Modern Artists Show How the Ancient Greeks & Romans Made Coins, Vases & Artisanal Glass

How the Ancient Greeks Shaped Modern Mathematics: A Short, Animated Introduction

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Someone has already made the real version. He is known as Clickspring on youtube. You can watch him build it in vivid detail, part by part, there.

Why is it assumed that humans made it?

Because most people are not retarded and don’t immediately attribute everything to “aliens or god” because we have no self confidence.