In his book on the Tarot, Alejandro Jodorowsky describes the Hermit card as representing mid-life, a “positive crisis,” a middle point in time; “between life and death, in a continual crisis, I hold up my lit lamp — my consciousness,” says the Hermit, while confronting the unknown. The figure recalls the image of Dante in the opening lines of the Divine Comedy. In Mandelbaum’s translation at Columbia’s Digital Dante, we see evident similarities:

When I had journeyed half of our life’s way,

I found myself within a shadowed forest,

for I had lost the path that does not stray.Ah, it is hard to speak of what it was,

that savage forest, dense and difficult,

which even in recall renews my fear:so bitter—death is hardly more severe!

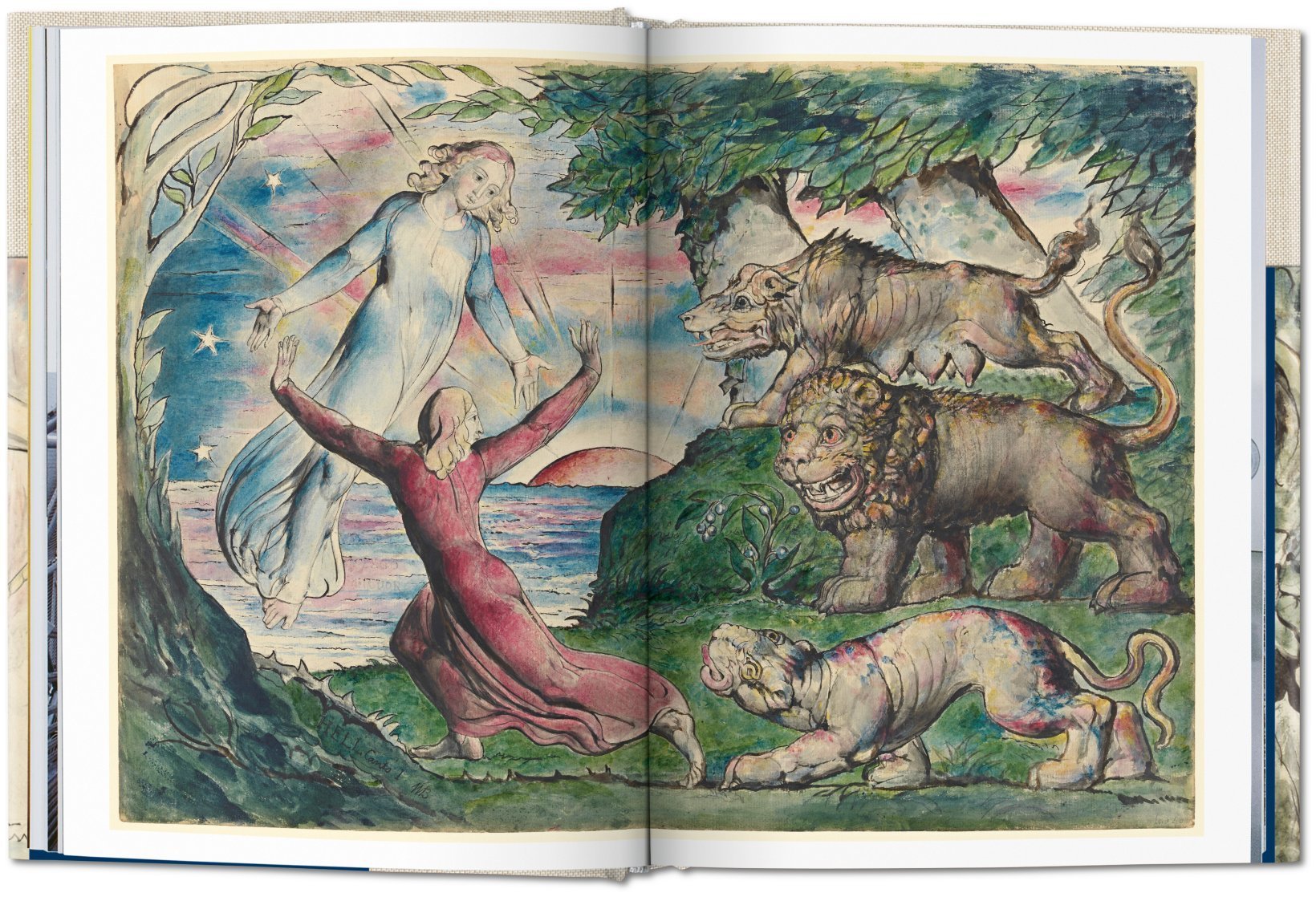

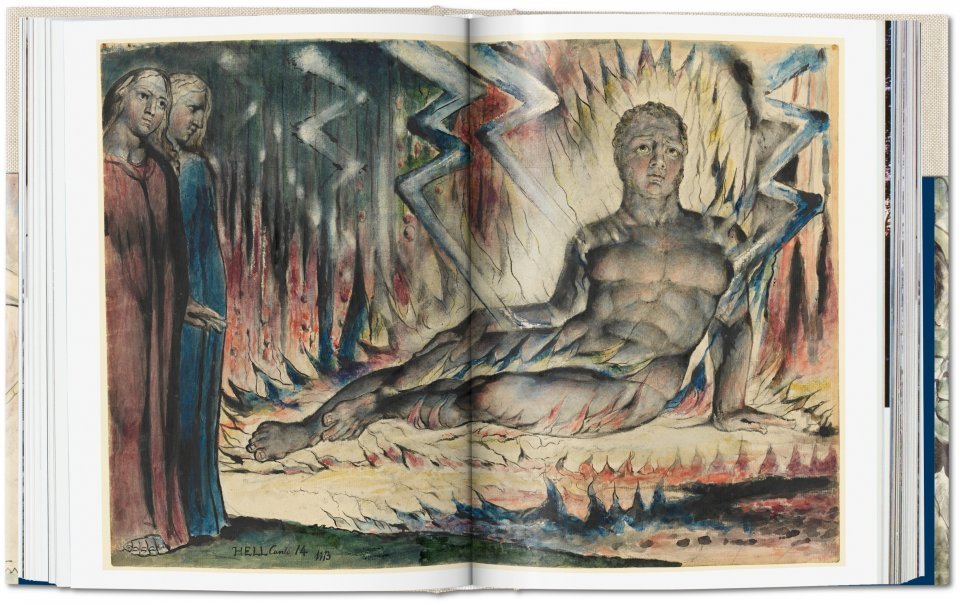

This is not to say the literary Dante and occult Hermeticism are historically related; only they emerged from the same matrix, a medieval Catholic Europe steeped in mysterious symbols. The Hermit is a portent, messenger, and guide, an aspect represented by the poet Virgil, whom William Blake — in 102 watercolor illustrations made between 1824 and 1827 — dressed in blue to represent spirit, while Dante wears his usual red — the color, in Blake’s system, of experience.

Blake did not read the Divine Comedy as a medieval Catholic believer but as a visionary 18th and 19th century English artist and poet who invented his own religion. He “taught himself Italian in order to be able to read the original” and had a “ complex relationship” with the text, writes Dante scholar Silvia De Santis.

His interpretation drew from a “widespread ‘selective use’” of the poet,” dating from 16th century English Protestant readings which saw Dante’s satirical skewering of corrupt individuals as indictments of the institutions they represent — the church and state for which Blake had no love.

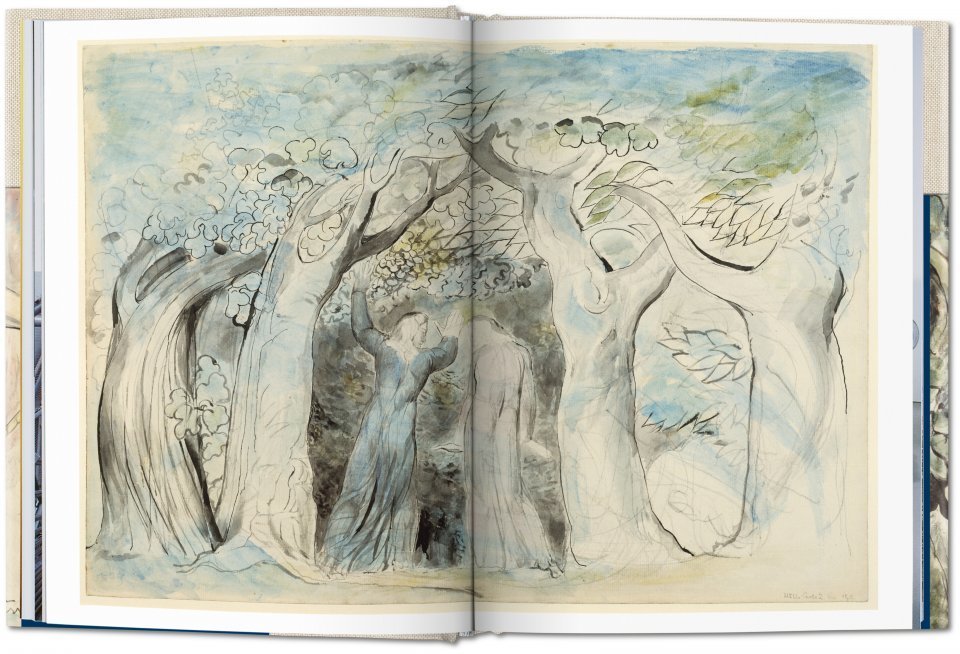

Approaching the project at the end of his life, not the middle, Blake drew primarily on themes that Dante scholar Robin Kilpatrick describes as a “searching analysis of all of the political and economic factors that had destroyed Florence .… Hell is a diagnosis of what, in so many ways, can prove to be divisive in human nature. Sin, for Dante, is not transgression of an ordinary kind … against some law… it’s a transgression against love.”

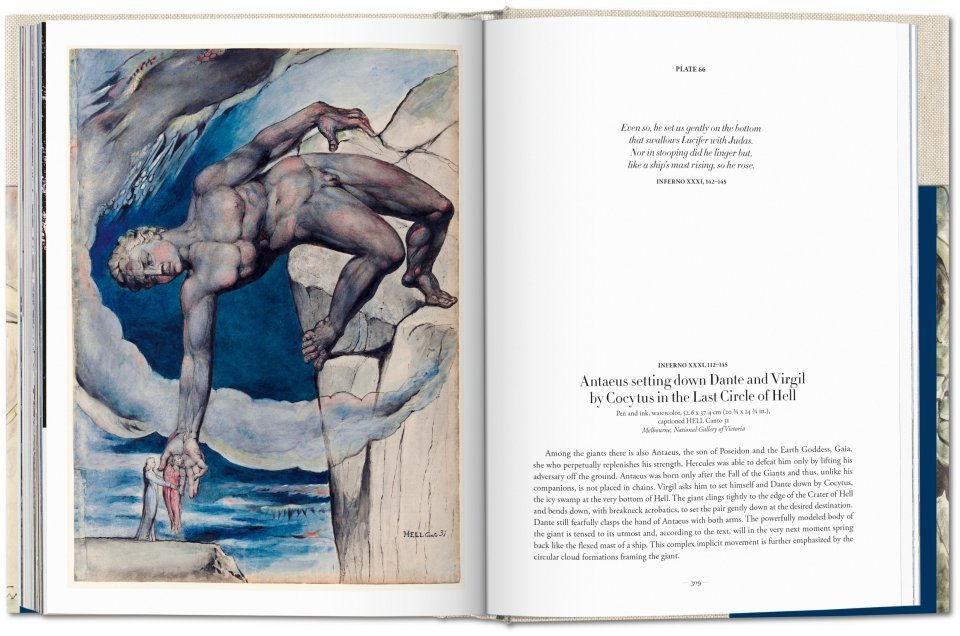

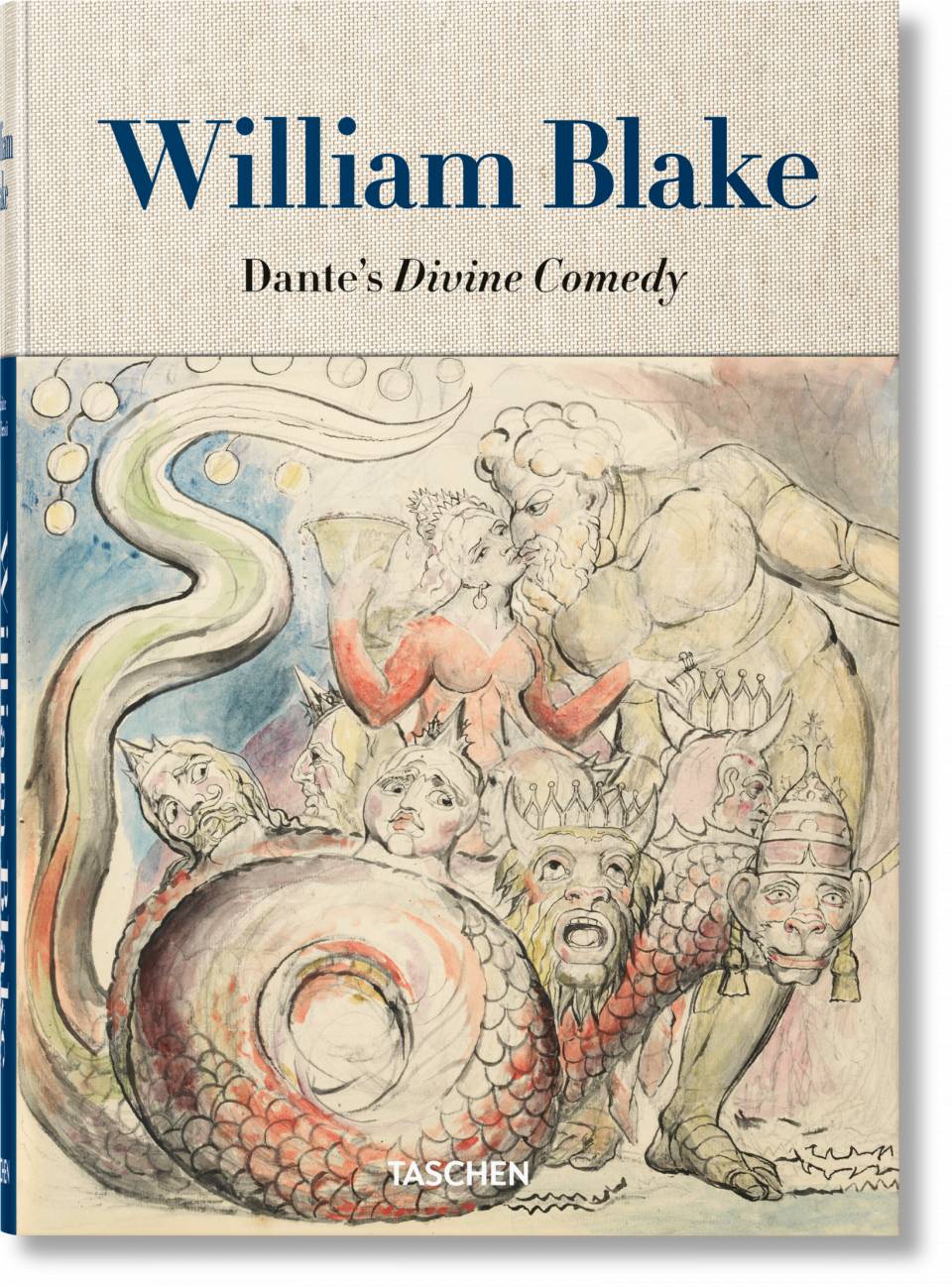

Blake died before he could finish the series, commissioned by his friend John Linnell in 1824. He had intended to engrave all 102 illustrations, conceived, he wrote, “during a fortnight’s illness in bed.” You can see all of his stunning watercolors online here and find them lovingly reproduced in a new book published by Taschen with essays by Blake and Dante experts, helping contextualize two poets who found a common language across a span of 500 years. The book, originally priced at $150, now sells for $40. A beautiful XL edition sells at a higher price.

Related Content:

A Digital Archive of the Earliest Illustrated Editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1487–1568)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Marvellous resource. Many thanks

A stunning “XL” edition is also available. 324 pages, 18x13 inches with 14 fold out spreads. It isn’t cheap, but new and used copies are available from independent book sellers. ISBN 9783836555128. These are my favorite illustrations of all time, and being able to enjoy such beautiful reproductions of them feels like a dream come true.