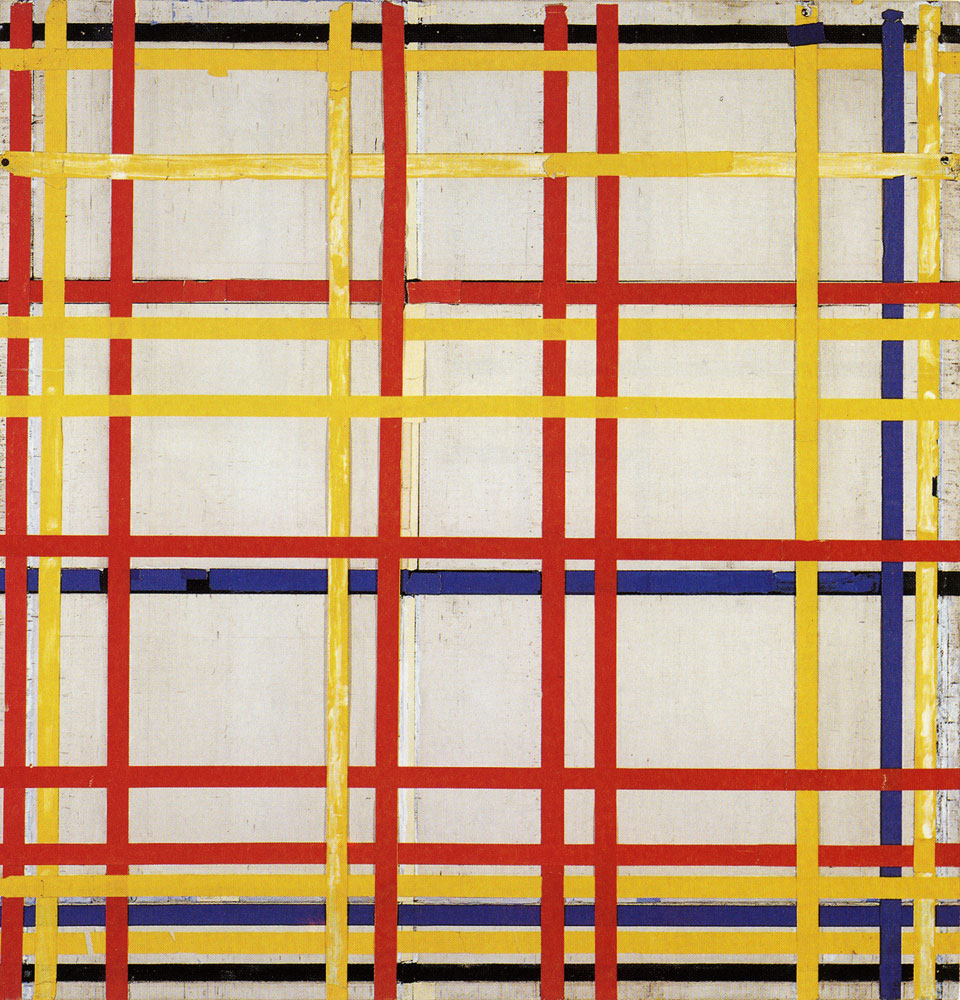

Piet Mondrian’s New York City I was recently discovered to have been hanging upside-down on display for the past 75 years, which made for a cultural story practically designed to go viral. Unsurprisingly, some of those keeping it in circulation have read it as proof positive of the fraudulence of “modern art.” How good could Mondrian be, after all, if nobody else over the past three-quarters of a century could tell that his painting wasn’t right-side-up? That isn’t a cogent criticism, of course: New York City I dates from 1941, by which time Mondrian’s work had long since become austere even by the standards of abstract art, employing only lines and blocks of color.

“The way the picture is currently hung shows the multicolored lines thickening at the bottom, suggesting an extremely simplified version of a skyline,” writes the Guardian’s Philip Oltermann.

But “the similarly named and same-sized oil painting, New York City, which is on display in Paris at the Centre Pompidou, has the thickening of lines at the top,” and “a photograph of Mondrian’s studio, taken a few days after the artist’s death and published in American lifestyle magazine Town and Country in June 1944, also shows the same picture sitting on an easel the other way up.” It was just such clues that Susanne Meyer-Büser, curator of the art collection of North Rhine-Westphalia, put together to diagnose its current mis-orientation.

Regardless, New York City I will remain as it is. The eight-decade-old strips of painted tape with which Mondrian assembled its black, yellow, red, and blue grid “are already extremely loose and hanging by a thread,” said Meyer-Büser. “If you were to turn it upside down now, gravity would pull it into another direction.” The artist’s signature would normally be a distraction in an inverted work, but since he didn’t consider this particular work finished, he never actually signed it — and if he had, of course, it would have been hung correctly in the first place. In any case, it’s hardly a stretch to imagine having a rich aesthetic experience with an upside-down Mondrian; could we say the same about, for instance, an upside-down Last Supper?

Related content:

Watch the Dutch Paint “the Largest Mondrian Painting in the World”

Philosopher Portraits: Famous Philosophers Painted in the Style of Influential Artists

What Happens When a Cheap Ikea Print Gets Presented as Fine Art in a Museum

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

This is an interpretation, not a proven fact. An inference. The curator who hung the work decades ago is not alive to defend himself.