Before electronic amplification, instrument makers and musicians had to find newer and better ways to make themselves heard among ensembles and orchestras and above the din of crowds. Many of the acoustic instruments we’re familiar with today—guitars, cellos, violas, etc.—are the result of hundreds of years of experimentation focused on solving just that problem. These hollow wooden resonance chambers amplify the sound of the strings, but that sound must escape, hence the circular sound hole under the strings of an acoustic guitar and the f‑holes on either side of a violin.

I’ve often wondered about this particular shape and assumed it was simply an affected holdover from the Renaissance. While it’s true f‑holes date from the Renaissance, they are much more than ornamental; their design—whether arrived at by accident or by conscious intent—has had remarkable staying power for very good reason.

As acoustician Nicholas Makris and his colleagues at MIT announced in a study published by the Royal Society, a violin’s f‑holes serve as the perfect means of delivering its powerful acoustic sound. F‑holes have “twice the sonic power,” The Economist reports, “of the circular holes of the fithele” (the violin’s 10th century ancestor and origin of the word “fiddle”).

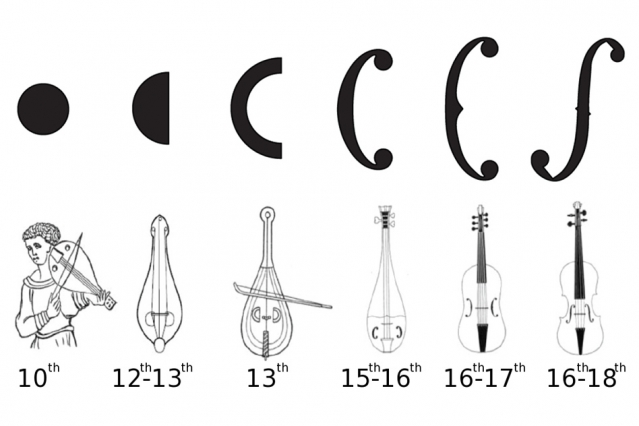

The evolutionary path of this elegant innovation—Clive Thompson at Boing Boing demonstrates with a color-coded chart—takes us from those original round holes, to a half-moon, then to variously-elaborated c‑shapes, and finally to the f‑hole. That slow historical development casts doubt on the theory in the above video, which argues that the 16th-century Amati family of violin makers arrived at the shape by peeling a clementine, perhaps, and placing flat the surface area of the sphere. But it’s an intriguing possibility nonetheless.

Instead, through an “analysis of 470 instruments… made between 1560 and 1750,” Makris, his co-authors, and violin maker Roman Barnas discovered, writes The Economist, that the “change was gradual—and consistent.” As in biology, so in instrument design: the f‑holes arose from “natural mutation,” writes Jennifer Chu at MIT News, “or in this case, craftsmanship error.” Makers inevitably created imperfect copies of other instruments. Once violin makers like the famed Amati, Stradivari, and Guarneri families arrived at the f‑hole, however, they found they had a superior shape, and “they definitely knew what was a better instrument to replicate,” says Makris. Whether or not those master craftsmen understood the mathematical principles of the f‑hole, we cannot say.

What Makris and his team found is a relationship between “the linear proportionality of conductance” and “sound hole perimeter length.” In other words, the more elongated the sound hole, the more sound can escape from the violin. “What’s more,” Chu adds, “an elongated sound hole takes up little space on the violin, while still producing a full sound—a design that the researchers found to be more power-efficient” than previous sound holes. “Only at the very end of the period” between the 16th and the 18th centuries, The Economist writes, “might a deliberate change have been made” to violin design, “as the holes suddenly get longer.” But it appears that at this point, the evolution of the violin had arrived at an “optimal result.” Attempts in the 19th century to “fiddle further with the f‑holes’ designs actually served to make things worse, and did not endure.”

To read the mathematical demonstrations of the f‑hole’s superior “conductance,” see Makris and his co-authors’ published paper here. And to see how a contemporary violin maker cuts the instrument’s f‑holes, see a careful demonstration in the video above.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Každý tvar nástroje dovoluje vytvořit v něm adekvátní zvukové otvory,aby tim neporušil estetický vzhled nástroje a jeho funkci.

It was cool hearing and reading about the history of instruments. As a guitar player its cool seeing and reading about all the similarities they have together when it comes to the making of it.

I never really thought about how the F holes and how they could change the sound of the instrument. It was very interesting to learn about the evolution of the f holes and how it started off as a simple circle. This article wants to me experiment with F holes and play instruments with circular holes instead of the normal f holes and compare them to how they sound.

ok buddy

go and practice