The name B.F. Skinner often provokes darkly humorous references to such bizarre ideas as “Skinner boxes,” which put babies in cage-like cribs, and put the cribs in windows as if they were air-conditioners, leaving the poor infants to raise themselves. Skinner was hardly alone in conducting experiments that flouted, if not flagrantly ignored, the ethical concerns now central to experimentation on humans. The code of conduct on torture and abuse that ostensibly governs members of the American Psychological Association did not exist. Radical behaviorists like Skinner were redefining the field. His work has come to stand for some of its worst abuses.

But Skinner has been mischaracterized in the popularization of his ideas — a popularization, it’s true, in which he enthusiastically took part. The actual “Skinner box” was cruel enough — an electrified cage for animal experimentation — but it was not the infant window box that often goes by the name. This was, instead, called an “aircrib” or “baby-tender,” and it was loaded with creature comforts like climate control and a complement of toys. “In our compartment,” Skinner wrote in a 1945 Ladies Home Journal article, “the waking hours are invariably active and happy ones.” Describing his first test subject, his own child, he wrote, “our baby acquitted an amusing, almost apelike skill in the use of her feet.”

Skinner was not a soulless monster who put babies in cages, but he also did not understand mammalian babies’ need for physical touch. Likewise, when it came to education, Skinner had ideas that can seem contrary to what we know works best, namely a variety of methods that honor different learning styles and abilities. Educators in the 1950s embraced far more regimented practices, and Skinner believed humans could be trained just like other animals. He treated an early experiment in classroom technology just like an experiment teaching pigeons to play ping-pong. It was, in fact, “the foundation for his education technology,” says education journalist Audrey Watters, “that we’ll build machines and they’ll give students — just like pigeons — positive reinforcement and students — just like pigeons — will learn new skills.”

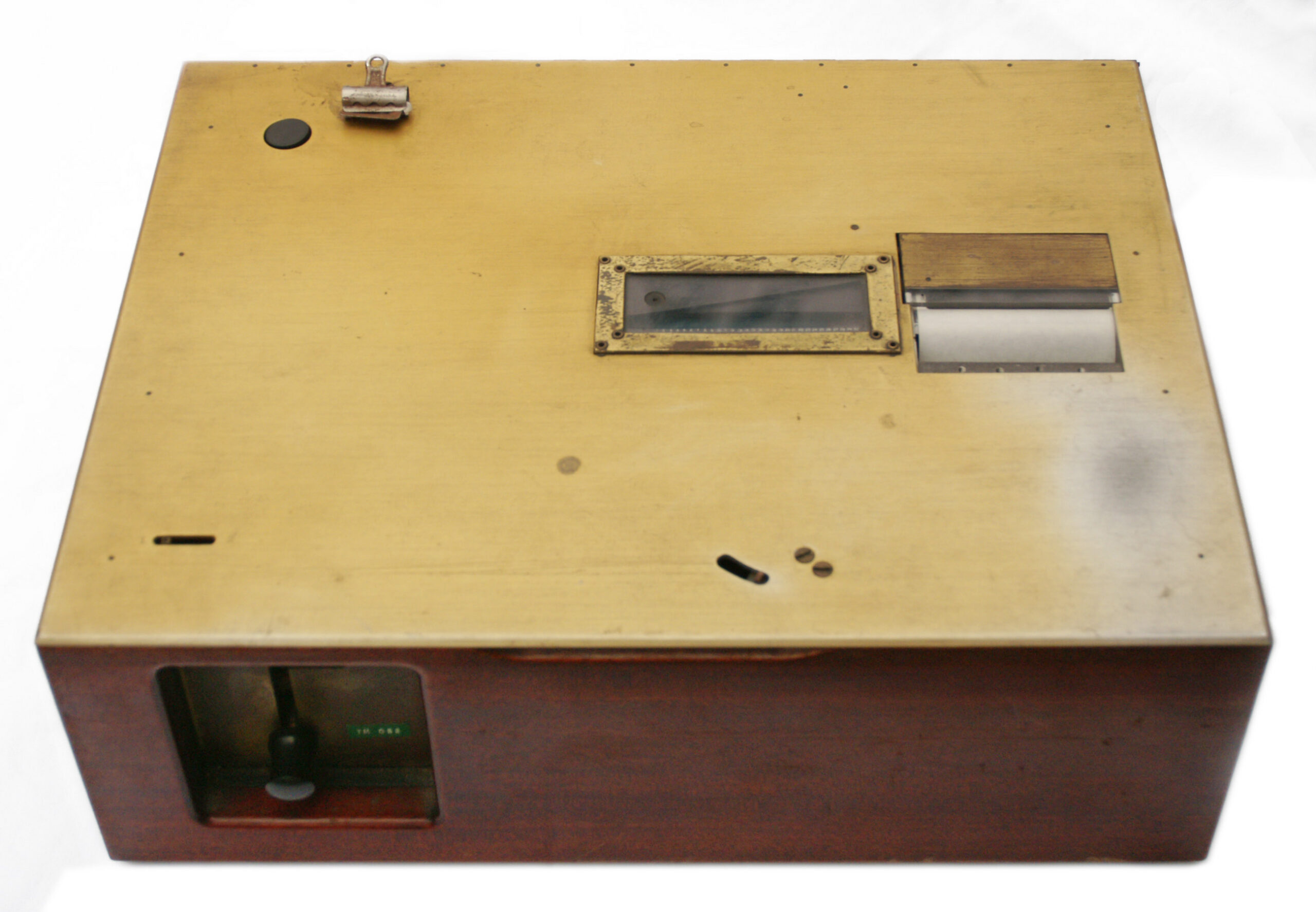

To this end, Skinner created what he called the Teaching Machine in 1954 while he taught psychology at Harvard. He was hardly the first to design such a device, but he was the first to invent a machine based on behaviorist principles, as Abhishek Solanki explains in a Medium article:

The teaching machine was composed of mainly a program, which was a system of combined teaching and test items that carried the student gradually through the material to be learned. The “machine” was composed of a fill-in-the-blank method on either a workbook or on a computer. If the student was correct, he/she got reinforcement and moved on to the next question. If the answer was incorrect, the student studied the correct answer to increasing the chances of getting reinforced next time.

Consisting of a wooden box, a metal lid with cutouts, and various paper discs with questions and answers written on them, the machine did adjust for different students’ needs, in a way. Skinner “noted that the learning process should be divided into a large number of very small steps and reinforcement must be dependent upon the completion of each step. He believed this was the best possible arrangement for learning because it took into account the rate of learning for each individual student.” He was again inspired by his own children, coming up with the machine after visiting his daughter’s school and deciding he could improve on things.

The method and means of learning, as you’ll see in the demonstration films above, were not individualized. “There was very, very little freedom in Skinner’s vision,” says Watters. “Indeed Skinner wrote a very well-known book, Beyond Freedom and Dignity in the early 1970s, in which he said freedom doesn’t exist.” While Skinner’s machine didn’t itself become widely used, his ideas about education, and education technology, are still very much with us. We see Skinner’s machine “taking new forms with adaptive teaching and e‑learning,” writes Solanki.

And we see the darker side of his design in classroom technology, says Watters, in an industry that profits from alienating, one-size-fits all ed-tech solutions. But she also sees “students who are resisting and communities who are building practices that serve their needs rather than serving the needs of engineers.” Skinner’s theories of conditioning were and are incredibly persuasive, but his reductive views of human nature seem to leave out more than they explain. Learn more about the history of teaching machines in Watters’ new book, Teaching Machines: The History of Personalized Learning.

Related Content:

Hermann Rorschach’s Original Rorschach Test: What Do You See? (1921)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness