Laughter is good medicine, but I’ve found little genuine humor in satire of the 2016 election and subsequent events. Political reality defies parody. So, I guess I wasn’t particularly amused by the idea of a comic staging of the Mueller Report. But aside from whether or not the report has comic potential, the exercise raises a more serious question: Should ordinary citizens read the report?

Given the snowjob summary offered by the Attorney General—and certain press outfits who repeated claims that it exonerated the president—probably. Especially (good luck) if they can score an unredacted copy. Yet, this raises yet another question: Does anyone actually want to read it? The answer appears to be a resounding yes. Even though it’s free, the [redacted] report is a bestseller.

And yet, “the published version is as dry as a [redacted] saltine,” writes James Poniewozik at The New York Times. “Robert Mueller himself has the stoic G‑man bearing of someone who would laugh by writing ‘ha ha’ on a memo pad.” (Now that’s a funny image.) One wonders how many people dutifully downloading it have stayed up late by the light of their tablets compelled to read it all.

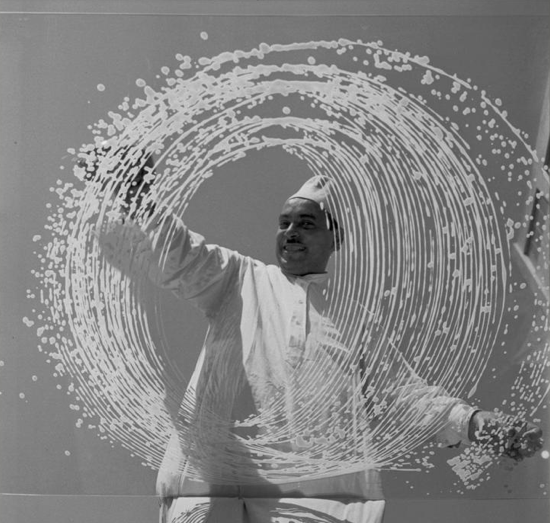

But of course, one does not approach any government document with the hopes of being entertained, though unintentional hilarity can leap from the page at any time. How should we approach The Investigation: A Search for the Truth in 10 Acts? Scripted by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Robert Schenkkan from the Mueller Report’s transcripts, the production is “part old-time public recitation,” writes Poneiwozik, and “part Hollywood table read.”

The staging above at New York’s Riverside Church was hosted by Law Works and performed live by a cast including Annette Bening, Kevin Kline, John Lithgow (as “Individual 1” himself), Michael Shannon, Justin Long, Jason Alexander, Wilson Cruz, Joel Gray, Kyra Sedgwick, Alfre Woodard, Zachary Quinto, Mark Ruffalo, Bob Balaban, Alyssa Milano, Sigourney Weaver, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Mark Hamill, and more. Bill Moyers serves as emcee.

Can this darkly comic production deliver some comic balm for having lived through the sordid reality of the events in question? It has its moments. Can it offer us something resembling truth? You be the judge. Or you be the producer, director, actor, etcetera. If you find value—civic, entertainment, or otherwise—in the exercise, Schenkkan encourages you to put on your own version of The Investigation. “Your production can be as modest or extravagant as you like,” he writes at Law Works, followed by a list of further instructions for a possible staging.

If, like maybe millions of other people, you’ve got an unread copy of the Mueller Report on your nightstand, maybe watching—or performing—The Investigation is the best way to get yourself to finally read it. Or the most grimly humorous, moronic, pathetic, and surreal parts of it, anyway.

Related Content:

Saturday Night Live: Putin Mocks Trump’s Poorly Attended Inauguration

The Mueller Report Is #1, #2 and #3 on the Amazon Bestseller List: You Can Get It Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness