Most young male fans from my generation failed to appreciate the gender imbalance in comic books. After all, what were the X‑Men without powerful X‑women Storm, Rogue, and, maybe the most powerful mutant of all, Jean Grey? Indie comics like Love and Rockets revolved around strong female characters, and if the legacy golden age Marvel and DC titles were nearly all about Great Men, well… just look at the time they came from. We shrugged it off, and also failed to appreciate how the hypersexualization of women in comics made many of the women around us uncomfortable and hyperannoyed.

Had we been curious enough to look, however, we would have found that golden age comics weren’t just innocent “products of their time”—they reflected a collective will, just as did the comics of our time. And the character who first challenged golden age attitudes about women—Wonder Woman, created in 1941—began her career as perhaps one of the kinkiest superheroes in mainstream comic books. What’s more, she was created by a psychologist William Moulton Marston, who first published under a pseudonym, due in part to his unconventional personal life. Marston, writes NPR, “had a wife—and a mistress. He fathered children with both of them, and they all secretly lived together in Rye, N.Y.”

The other woman in Marston’s polyamorous threesome, one of his former students, happened to be the niece of Margaret Sanger, and Marston just happened to be the creator of the lie detector. The details of his life are as odd and prurient now as they were to readers in the 1940s—partly an index of how little some things have changed. And now that Marston’s creation has finally received her blockbuster due, his story seems ripe for the Hollywood telling. Such it has received, it appears, in Professor Marston & the Wonder Women, the upcoming biopic by Angela Robinson. It’s unfair to judge a film by its trailer, but in the clips above we see much more of Marston’s dual romance than we do of the invention of his famous heroine.

Yet as political historian Jill Lepore tells it, the cultural history of Wonder Woman is as fascinating as her creator’s personal life, though it may be impossible to fully separate the two. A press release accompanying Wonder Woman’s debut explained that Marston aimed “to set up a standard among children and young people of strong, free, courageous womanhood; to combat the idea that women are inferior to men, and to inspire girls to self-confidence in athletics, occupations and professions monopolized by men.” It went on to express Marston’s view that “the only hope for civilization is the greater freedom, development and equality of women in all fields of human activity.”

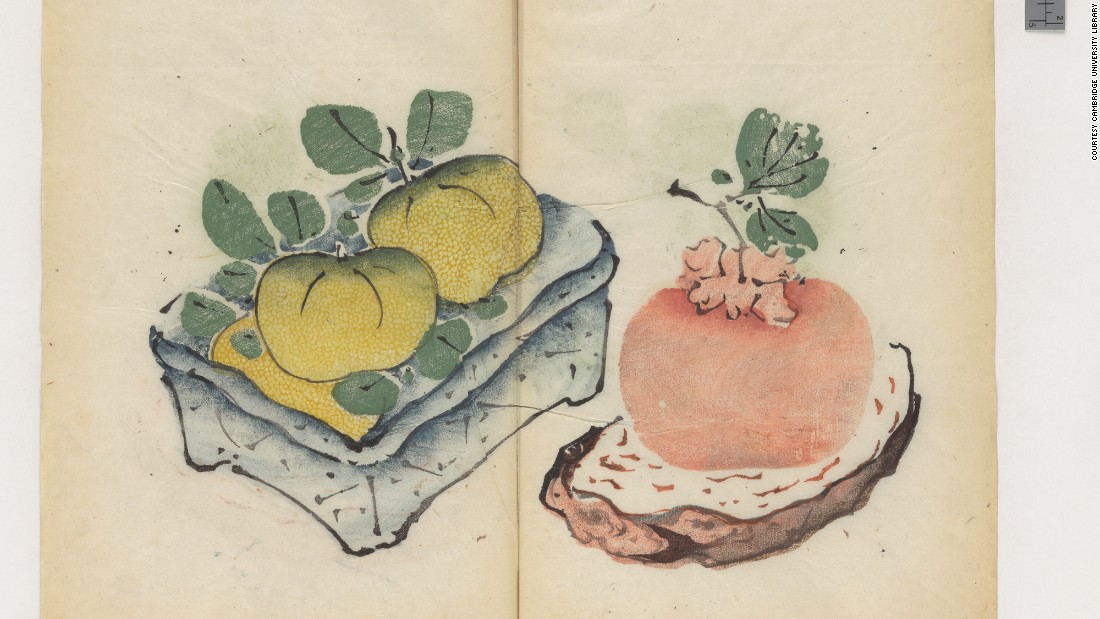

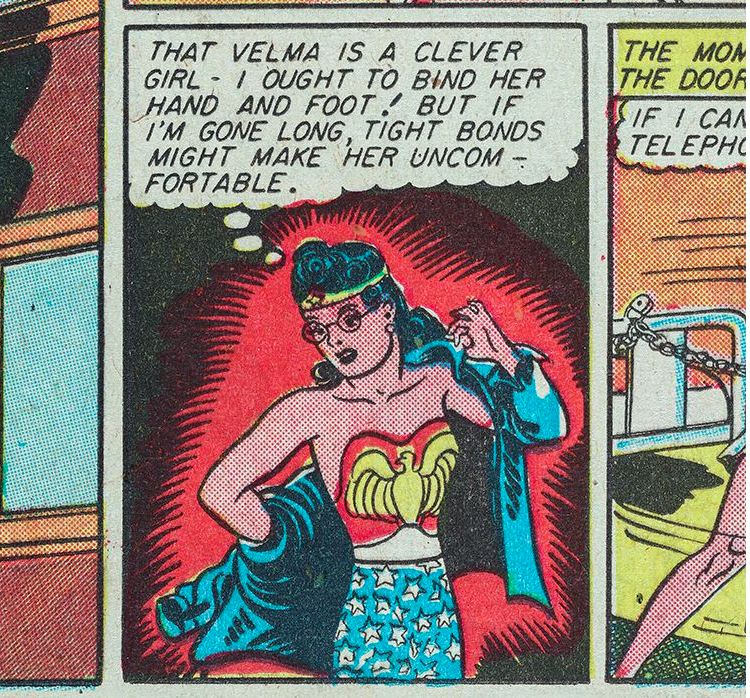

The language sounds like that of many a modern-day NGO, not a World War II-era popular entertainment. But Marston would go further, saying, “Frankly, Wonder Woman is the psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world.” His interest in domineering women and S&M drove the early stories, which are full of bondage imagery. “There are a lot of people who get very upset at what Marston was doing…,” Lepore told Terry Gross on Fresh Air. “’Is this a feminist project that’s supposed to help girls decide to go to college and have careers, or is this just like soft porn?’” As Marston understood it, the latter question could be asked of most comics.

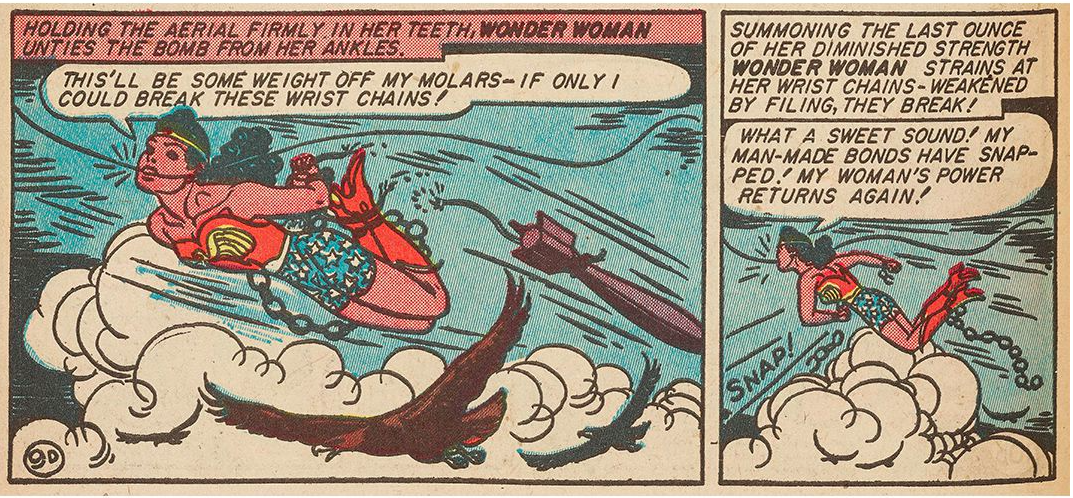

When writer Olive Richard—pen name of Marston’s mistress Olive Byrne—asked him in an interview for Family Circle whether some comics weren’t “full of torture, kidnapping, sadism, and other cruel business,” he replied, “Unfortunately, that is true.” But “the reader’s wish is to save the girl, not to see her suffer.” Marston created a “girl”—or rather a superhuman Amazonian princess—who saved herself and others. “One of the things that’s a defining element of Wonder Woman,” says Lepore, “is that if a man binds her in chains, she loses all of her Amazonian strength. So in almost every episode of the early comics, the ones that Marston wrote… she’s chained up or she’s roped up.” She has to break free, he would say, “in order to signify her emancipation from men.” She does her share of roping others up as well, with her lasso of truth and other means.

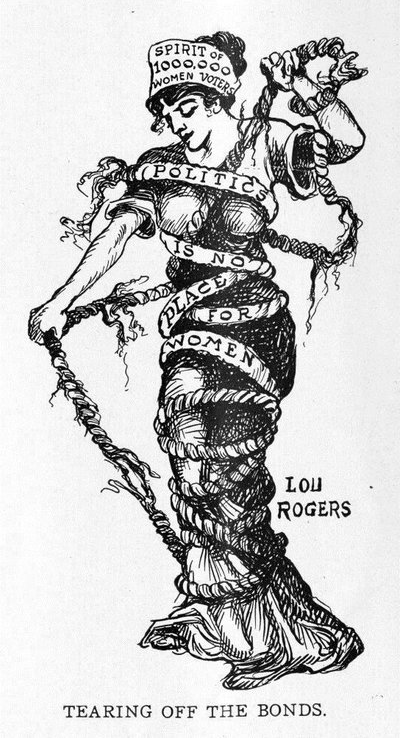

The seemingly clear bondage references in all those ropes and chains also had clear political significance, Lepore explains. During the fight for suffrage, women would chain themselves to government buildings. In parades, suffragists “would march in chains—they imported that iconography from the abolitionist campaigns of the 19th century that women had been involved in… Chains became a really important symbol,” as in the 1912 drawing below by Lou Rogers. Wonder Woman’s mythological origins also had deeper signification than the male fantasy of a powerful race of well-armed dominatrices. Her story, writes Lepore at The New Yorker, “comes straight out of feminist utopian fiction” and the fascination many feminists had with anthropologists’ speculation about an Amazonian matriarchy.

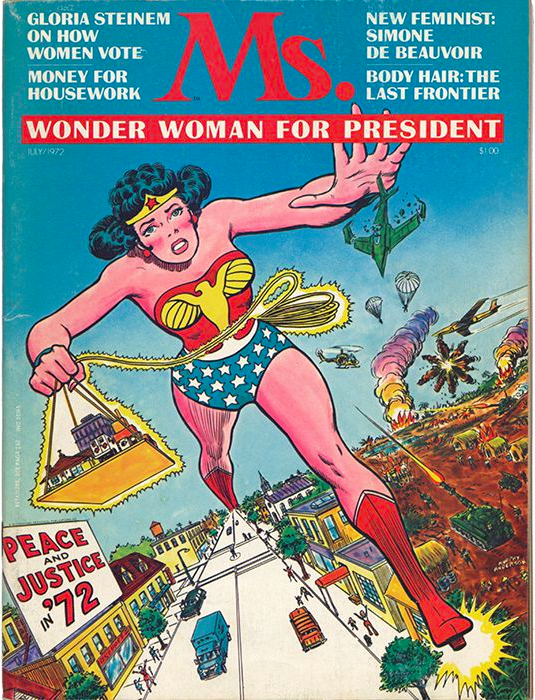

The combination of feminist symbols have made the character a redoubtable icon for every generation of activists—as in her appearance on 1972 cover of Ms. magazine, further up, an issue headlined by Gloria Steinem and Simone de Beauvoir. Marston translated the feminist ideas of the suffrage movement, and of women like Margaret Sanger, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, his wife, lawyer Elizabeth Holloway Marston, and his mistress Olive Byrne, into a powerful, long-revered superhero. He also translated his own ideas of what Havelock Ellis called “the erotic rights of women.”

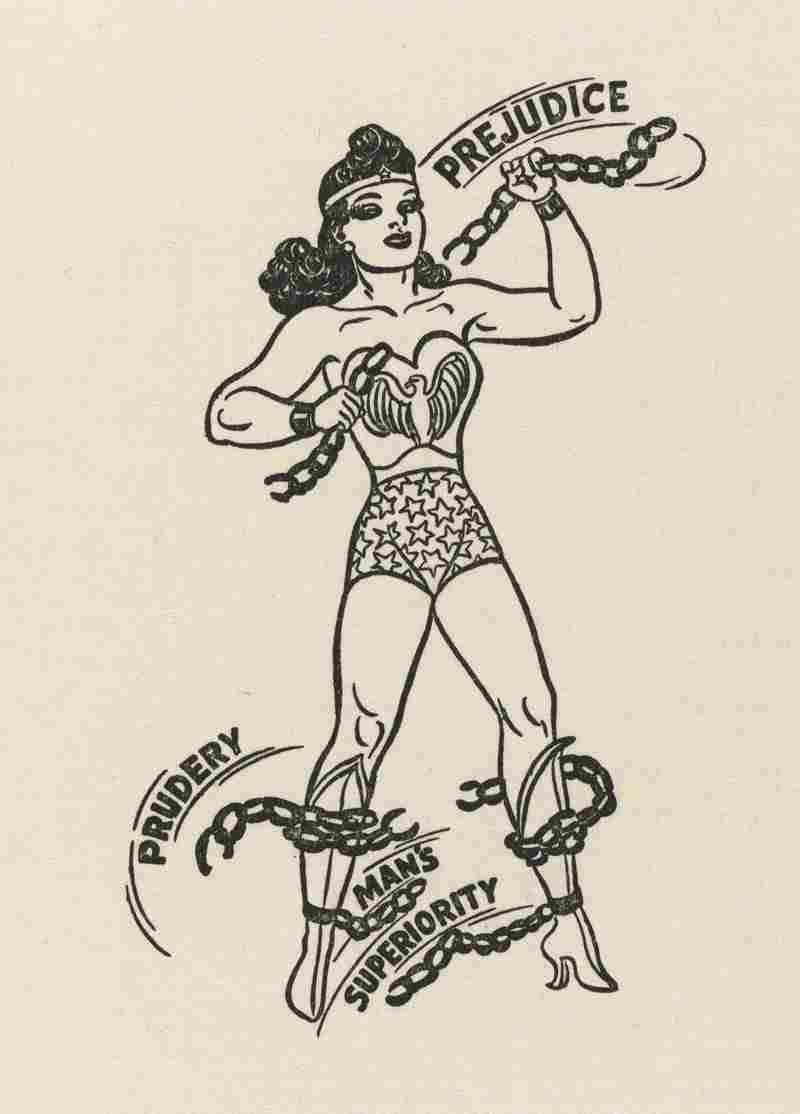

Marston’s version of Wonder Woman (he stopped writing the comic in 1947) had as much agency—sexual and otherwise—as any male character of the time. (See her breaking the bonds of “Prejudice,” “Prudery,” and “Man’s Superiority” in a drawing, below, from Marston’s 1943 article “Why 100,000 Americans Read Comics.”) The character was undoubtedly kinky, a quality that largely disappeared from later iterations. But she was not created, as were so many women in comics in the following decades, as an object of teenage lust, but as a radically liberated feminist hero. Read more about Marston in Lepore’s essays at Smithsonian and The New Yorker and in her book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman.

Related Content:

Download Over 22,000 Golden & Silver Age Comic Books from the Comic Book Plus Archive

Free Comic Books Turns Kids Onto Physics: Start With the Adventures of Nikola Tesla

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness