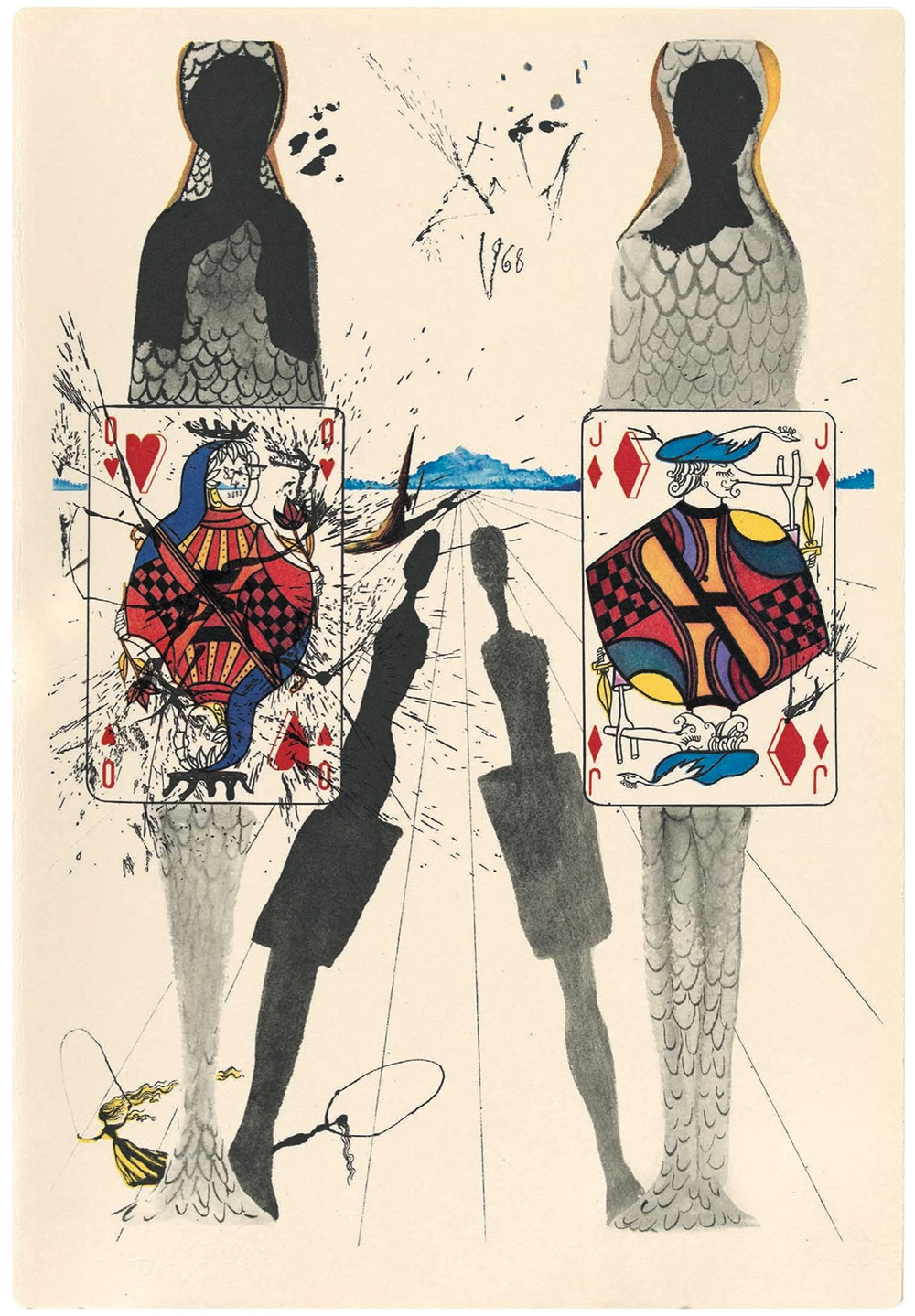

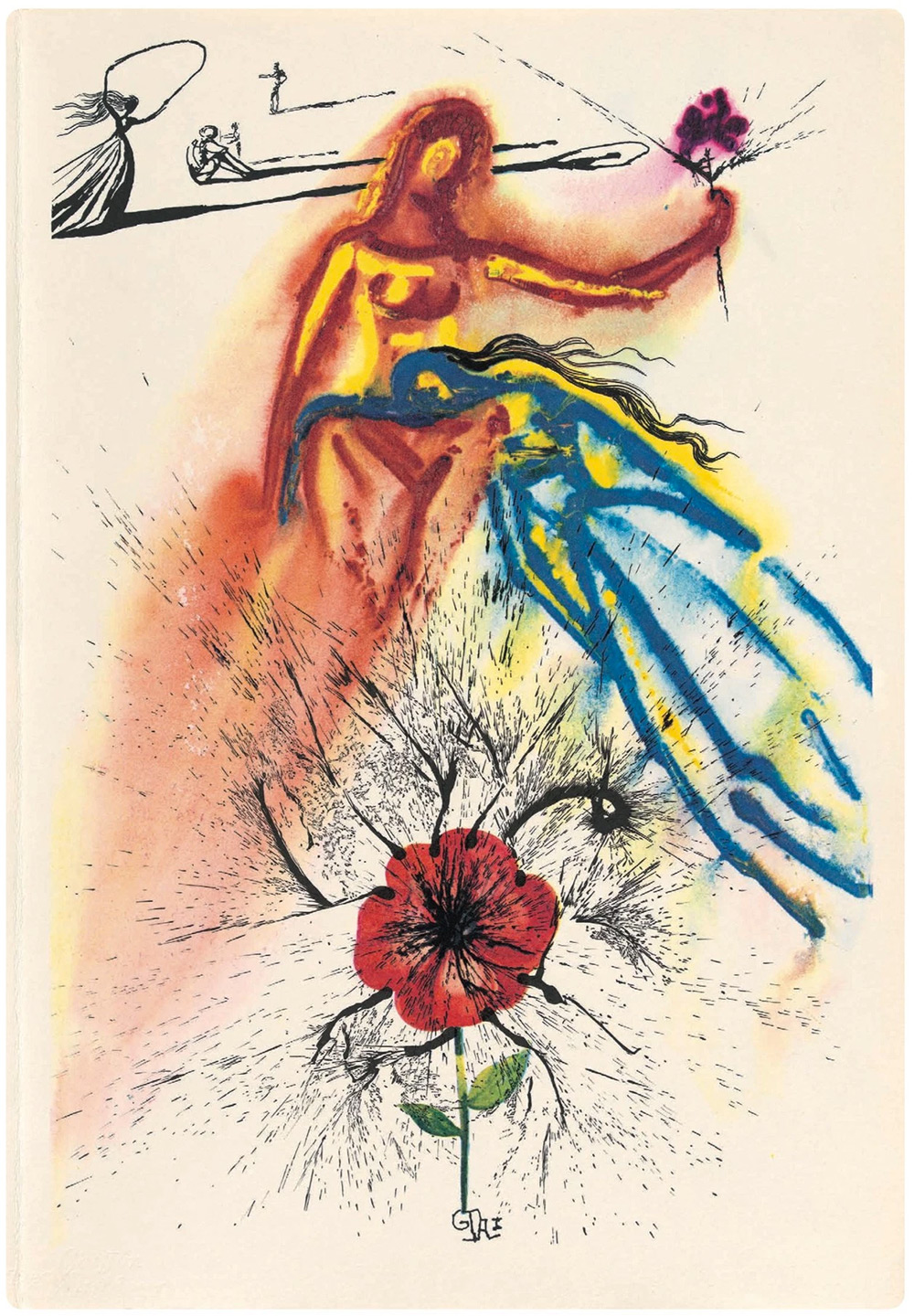

On canvas and paper, Salvador Dalí created apparently nonsensical realities that nevertheless operated according to logic all their own; in writing, Lewis Carroll, author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, did the very same. It thus only makes sense, despite their differences in nationality and sensibility as well as their barely overlapping life spans, that their artistic worlds — one with its grotesquely misshapen objects, obscure symbols, and hauntingly empty vistas, the other full of wordplay, whimsy, and mathematics — would one day collide. It happened in 1969, when an editor at Random House commissioned the master surrealist to create illustrations for an exclusive edition of Carroll’s timeless story for the house’s book-of-the-month club.

“Dalí created twelve heliogravures — a frontispiece, which he signed in every copy from the edition, and one illustration for each chapter of the book,” writes Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova. “For more than half a century, this unusual yet organic cross-pollination of genius remained an almost mythic artifact, reserved for collectors and scholars,” until Princeton University Press saw fit to reprint it for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’s 150th anniversary (much as Taschen recently reissued Dalí’s bizarre cookbook Les Diners de Gala). Sweetening the deal still further, they’ve included essays by mathematician and Dalí collaborator Thomas Banchoff as well as Lewis Carroll Society of North America president Mark Burstein.

“Although the outrageousness of Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, who came up with the pen name Lewis Carroll in 1856, was limned within a conventional fairy tale,” writes Burstein, “the surrealists deliberately sought outrage and provocation in their art and lives and questioned the nature of reality. For both Carroll and the surrealists, what some call madness could be perceived by others as wisdom.” He describes surrealism’s initial objective as making “accessible to art the realms of the unconscious, the irrational, and the imaginary, and its influence soon went far beyond the visual arts and literature, embracing music, film, theater, philosophy, and popular culture. As have the Alice books.” And with so many realms of the unconscious, the irrational, and the imaginary left to explore, this intersection of Carroll and Dalí’s different yet compatible methods of exploration should hold more appeal than ever.

You can find copies of the Princeton reissue of Dalí’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland here.

Related Content:

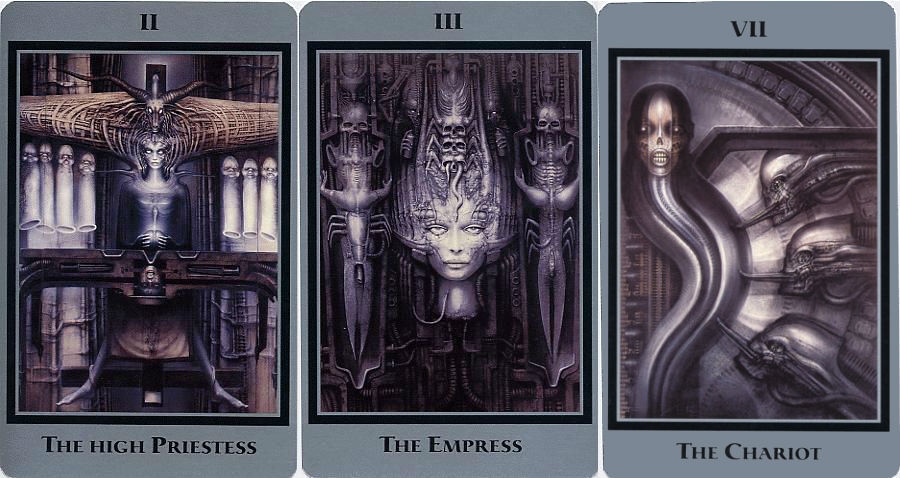

The Tarot Card Deck Designed by Salvador Dalí

Salvador Dalí’s 1973 Cookbook Gets Reissued: Surrealist Art Meets Haute Cuisine

Salvador Dalí’s Avant-Garde Christmas Cards

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.