Image by Raffi Asdourian, via Wikimedia Commons

Asked to list their favorite films of all times, most directors tend towards the canon. And why not? 8 1/2–loved by Scorsese and Lynch and many others–is an indisputable masterpiece, for example. So is The Godfather, Rashomon, Vertigo, and any number of movies that make top film lists over and over. The point is, most of the time, these lists are samey.

That’s why this list from Wes Anderson is a hoot. Here he’s not asked to list his favorites of all time, but rather to create a Top 10 list of Criterion titles. Yet here’s his M.O.: “I thought my take on a top-ten list might be to simply quote myself from the brief fan letters I periodically write to the Criterion Collection team,” he says.

A lot of these films are rarities, and Anderson admits he’s only just seen some of them for the first time. Martin Ritt’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is one. Roberto Rossellini’s The Taking of Power by Louis XIV is another. Of the latter, he says, “This is a wonderful and very strange movie. I had never heard of it. The man who plays Louis cannot give a convincing line reading, even to the ears of someone who can’t speak French—and yet he is fascinating.”

Anderson’s comments are often questions, not definitive statements. Like us, he is just as mystified by a film, and that feeling is probably why he likes them in the first place.

Of that Rossellini film he wonders “What does good acting actually mean?” And of Claude Sautet’s Classe tous risques he asks, “Who is our Lino Ventura?” referring to the Italian-born French actor who was once described as “The French John Wayne.” (So, the real question is this: who is our modern day John Wayne?)

We’ll leave the rest for you to read, but for a director so invested in artifice and nostalgia it was a surprise to hear how much he loves surrealist Luis Buñuel:

“He is my hero. Mike Nichols said in the newspaper he thinks of Buñuel every day, which I believe I do, too, or at least every other.”

Wes Anderson’s Criterion Collection Top 10

1. The Earrings of Madame de… (dir. Max Ophuls)

2. Au hasard Balthazar (dir. Robert Bresson)

3.Pigs and Battleships/The Insect Woman/Intentions of Murder (dir. Shohei Imamura)

4. The Taking of Power by Louis XIV (dir. Roberto Rossellini)

5. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (dir. Martin Ritt)

6. The Friends of Eddie Coyle (dir. Peter Yates)

7. Classe tous risques (dir. Claude Sautet)

8. L’enfance nue (dir. Maurice Pialat)

9. Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (dir. Paul Schrader)

10. The Exterminating Angel (dir. Luis Buñuel)

Related Content:

Watch Wes Anderson’s Charming New Short Film, Castello Cavalcanti, Starring Jason Schwartzman

Wes Anderson from Above. Quentin Tarantino From Below.

Stanley Kubrick’s List of Top 10 Films: The First and Only List He Ever Created

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

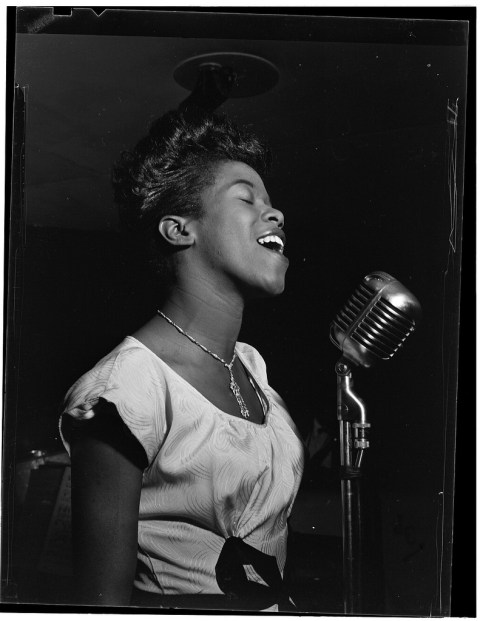

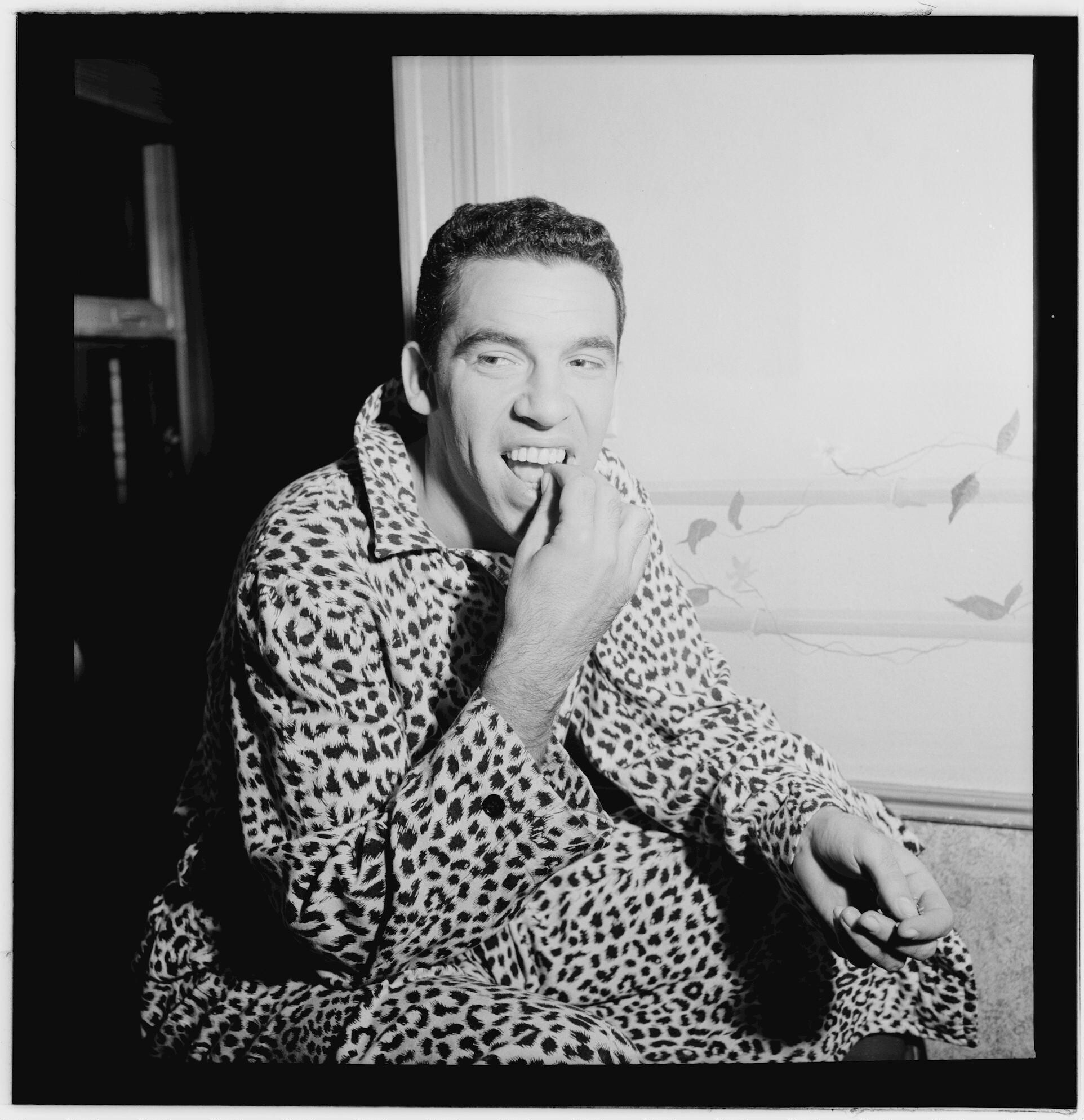

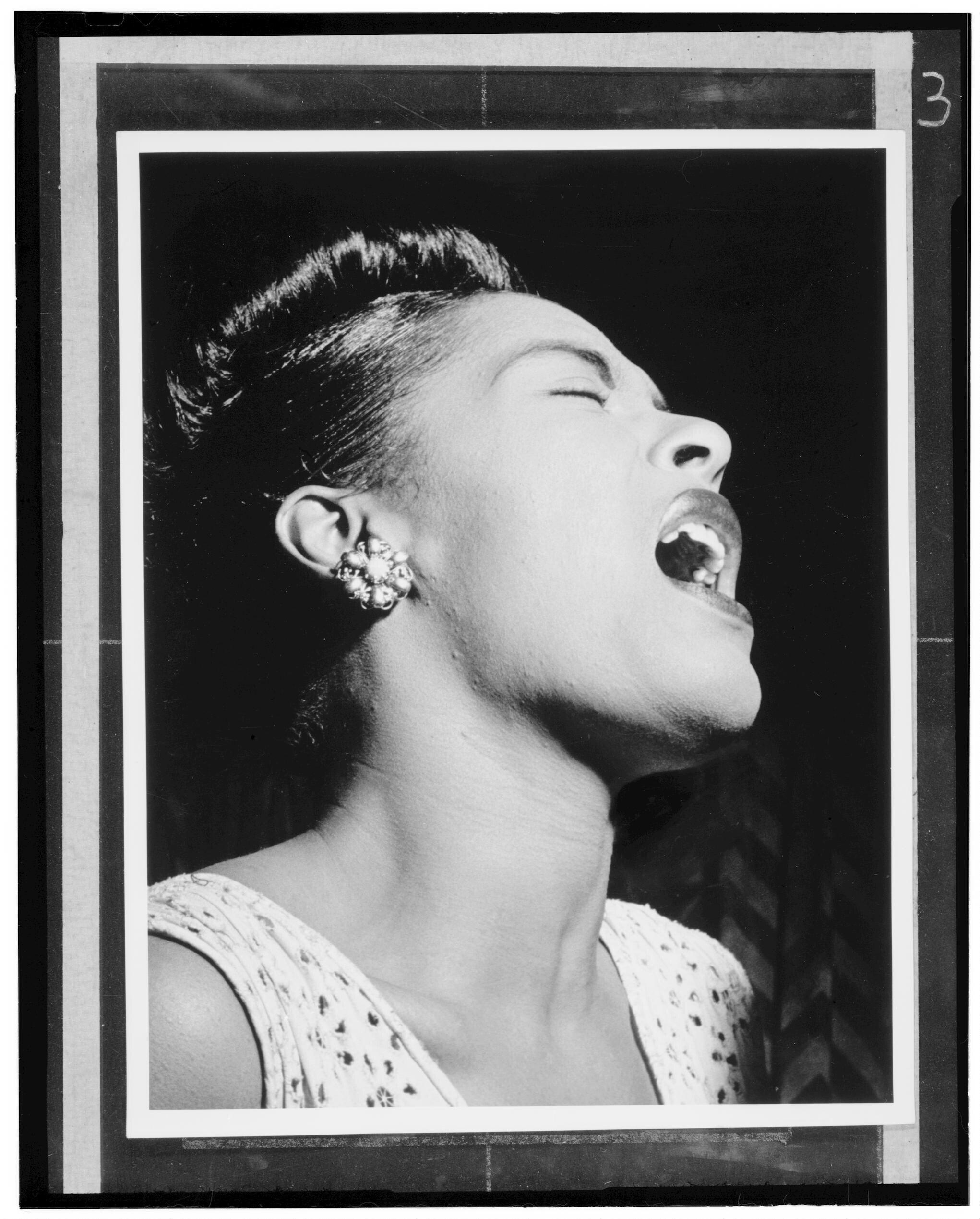

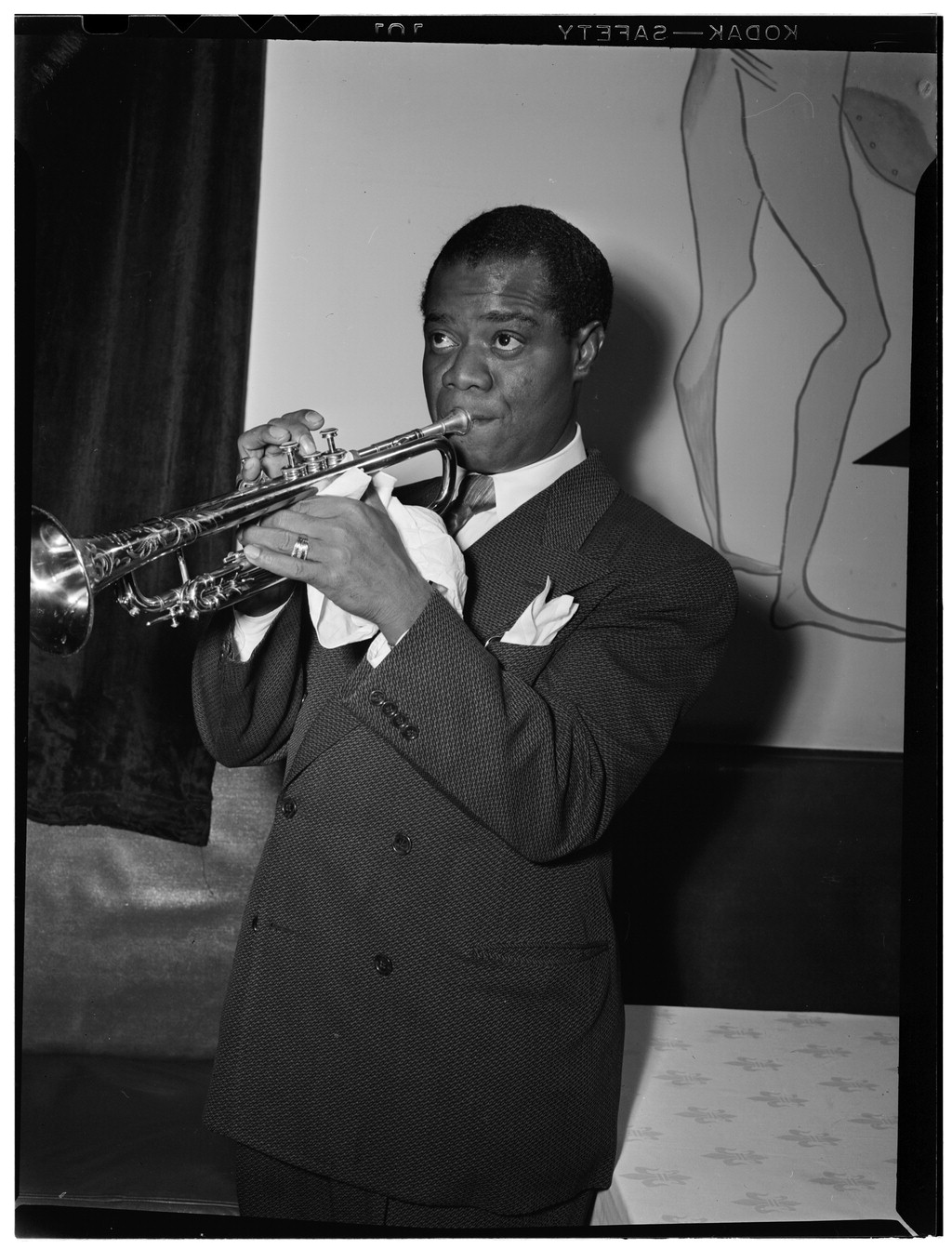

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.