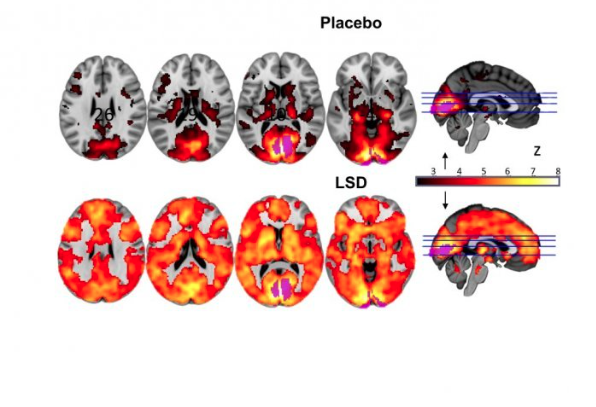

The refinements of medical imaging technologies like fMRI have given neuroscientists, psychologists, and philosophers better tools with which to study how the brain responds to all sorts of stimuli. We’ve seen studies of the brain on Jane Austen, the brain on LSD, the brain on jazz improv…. Music, it seems, offers an especially rich field for brain research, what with its connection to language, bodily coordination, mathematics, and virtually every other area of human intelligence. Scientists at MIT have even discovered which specific regions of the brain respond to music.

And yet, though we might think of music as a discrete phenomenon that stimulates isolated parts of the brain, Brownell professor of philosophy Dan Lloyd has a much more radical hypothesis, “that brain dynamics resemble the dynamics of music.”

He restates the idea in more poetic terms in an article for Trinity College: “All brains are musical—you and I are symphonies.” Plenty of people who can barely whistle on key or clap to a beat might disagree. But Lloyd doesn’t mean to suggest that we all have musical talent, but that—as he says in his talk below—“everything that goes on in the brain can be interpreted as having musical form.”

To demonstrate his theory, Lloyd chose not a musician or composer as a test subject, but another philosopher—and one whose brain he particularly admires—Daniel Dennett. And instead of giving us yet more colorful but baffling brain images to look at, he chose to convert fMRI scans of Dennett’s brain—“12 gigabytes of 3‑d snapshots of his cranium”—into music, turning data into sound through a process called “sonification.” You can hear the result at the top of the post—the music of Dennett’s brain, which is apparently, writes Daily Nous, “a huge Eno fan.”

In his paper “Mind as Music,” Lloyd argues that the so-called “language of thought” is, in fact, music. As he puts it, “the lingua franca of cognition is not a lingua at all,” an idea that has “aftershocks for semantics, method, and more.” Several questions arise: I, for one, am wondering if all our brains sound like Dennett’s abstract ambient score, or if some play waltzes, some operas, some psychedelic blues.…

You can learn much more about Lloyd’s fascinating research in his talk, which simplifies the technical language of his paper. Lloyd’s work goes much further, as he says, than studying “the brain on music”; instead he makes a sweepingly bold case for “the brain as music.”

via Daily Nous

Related Content:

This is Your Brain on Jazz Improvisation: The Neuroscience of Creativity

The Neuroscience of Drumming: Researchers Discover the Secrets of Drumming & The Human Brain

New Research Shows How Music Lessons During Childhood Benefit the Brain for a Lifetime

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness