Early 20th century modernism often seems to come out of nowhere, especially when our exposure to it comes in the form of a survey of singular great works. Each sculpture, film, or painting can seem sui generis, as though left by an alien civilization for us to find and admire.

But when you spend a great deal more time with modern art—looking over artists’ entire body of work and seeing how various schools and individuals developed together—it becomes apparent that all art, even the most radical or strange, evolves in dialogue with art, and that no artist works fully in isolation.

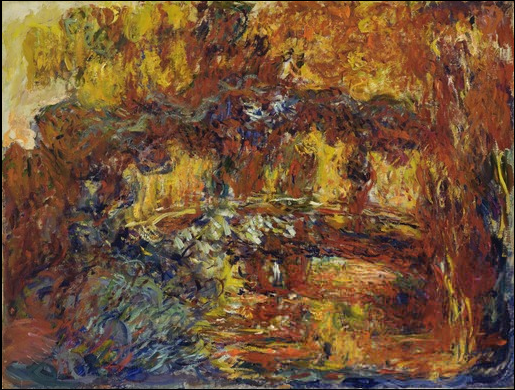

Take, for example, Monet’s Japanese Footbridge, above, from 1920. It’s a scene from his garden the early impressionist had painted many times over the decades. In this, one of his final paintings of the bridge, we see a riot of reds, oranges, and yellows in gestural brushstrokes that almost obscure the scene entirely. Though we know Monet had failing eyesight due to cataracts, a condition that lead to the vivid colors he saw in this period, it’s hard not to see some homage to Van Gogh, upon whose work Monet’s had a tremendous influence.

Above, we have Georgia O’Keeffe’s Lake George, Coat and Red from 1919, which abstracts the vivid patches of color characteristic of Edouard Manet’s work and the fauvism of Henri Matisse, both of whom greatly influenced American modernists like O’Keeffe, Edward Hopper, and Charles Demuth. These paintings reside at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), along with many thousands more that show us the development and interrelationship of modern art in Europe and America. And you can see close to half of them, whether they’re on display or not, at the MoMA’s digital collection.

This online collection houses 90,000 works of art in all, to be precise. You can see, for example, Giorgio de Chirico’s The Song of Love, above, a typical painting for the surrealist that shows how much influence he had on the later Salvador Dali, who was only ten years old at the time of this work. At the top of the post, Fernand Leger’s Three Women, from 1921, shows the futurist and later pop art French painter in conversation with Picasso and Henri Rousseau.

In other instances, we see works that seem anomalous in an artist’s canon, such as Marc Chagall’s 1912 Calvary, above. Known for his depictions of folklore and urban Jewish life, this early work from the same year as The Fiddler (the inspiration for Fiddler on the Roof) shows a much more polished cubist style, and a subject matter that anticipates his “darker” crucifixion series during and after World War II. To begin searching the MoMA’s collection of 90,000 online works, you can begin here with a wide variety of parameters. To browse the collection of early 20th century modernists in which I found these amazing works, start here.

Related Content:

Free: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Offer 474 Free Art Books Online

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Puts 400,000 High-Res Images Online & Makes Them Free to Use

Download 100,000 Free Art Images in High-Resolution from The Getty

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Launches Free Course on Looking at Photographs as Art

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness