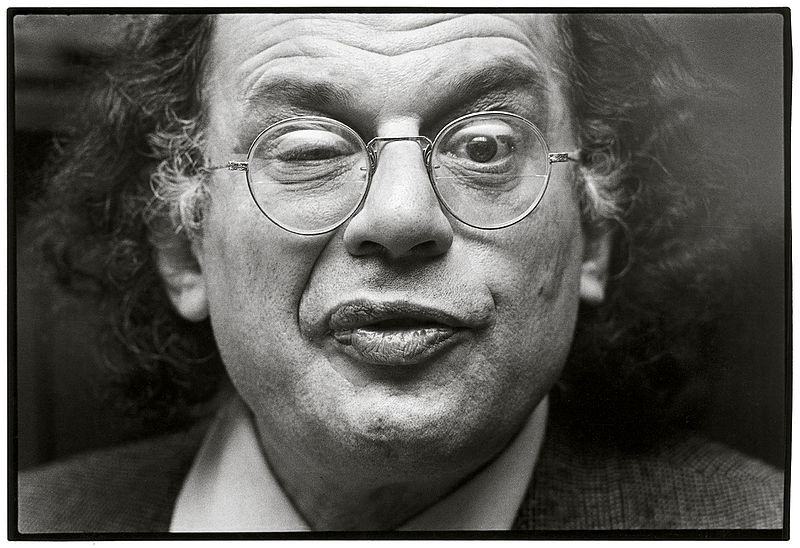

Which living writer stands as the heir to Edgar Allan Poe? A silly question, admittedly: now, more than 160 years after his death, Poe’s influence has spread so far and wide throughout literature that no one writer’s work could possibly count as his definitive continuation. The most popular and powerful modern storytellers owe more than a thing or two to Poe — or rather, have built upon Poe’s achievements — without even knowing it, especially if they hail from a different part of the world and work a different part of the cultural map than did 19th-century America’s pioneer of new and psychologically intense genre literature.

Take, for instance, Neil Gaiman. “Every year, Worldbuilders holds a giant auction-charity-donation thing, giving people cool things and raising an awful lot of money for a fantastic cause,” he says in the video above, which came out just this holiday season. “And every year, I seem to be reading a poem or book chosen by the people who pay money to Worldbuilders.

This year, for reasons known only to themselves, they have decided I need to read Edgar Allan Poe’s ghastly, gruesome, dark, and famous poem ‘The Raven.’ So I’ve lit a number of candles, fired up the fire, found a copy of the Oxford Book of Narrative Verse, and I’m going to read it to you in a comfortable chair by the fire, as befits a poem told in the days of yore.”

Though many of his fans come to know him through his novels like American Gods and Stardust, Gaiman’s writing career has also included work in poetry, comic books, radio drama, and movies, all of it using his signature mix of fantastical invention, resonant emotion, and polished, witty wordcraft. When potential collaborators on projects in these fields and others want to work with him, they want to tap not just his uncommon storytelling skill, regardless of the medium in which he tells his stories, but his ability to satisfy both wide audiences and critics with those stories.

Poe, too, knew how to do this, and indeed described “The Raven” in a magazine essay as a work deliberately composed to “suit at once the popular and the critical taste,” and since its first publication in 1845, the poem has only grown better-known and more beloved. Here, in Neil Gaiman’s ten-minute reading, we can see and hear one master of high-impact storytelling acknowledging another over all those 171 years.

Gaiman’s reading will be added to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

Related Content:

The Great Stan Lee Reads Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven”

James Earl Jones Reads Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” and Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”

Lou Reed Rewrites Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.” See Readings by Reed and Willem Dafoe

John Astin, From The Addams Family, Recites “The Raven” as Edgar Allan Poe

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.